- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Order and mayhem

- Article Subtitle: A stimulating history of America

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

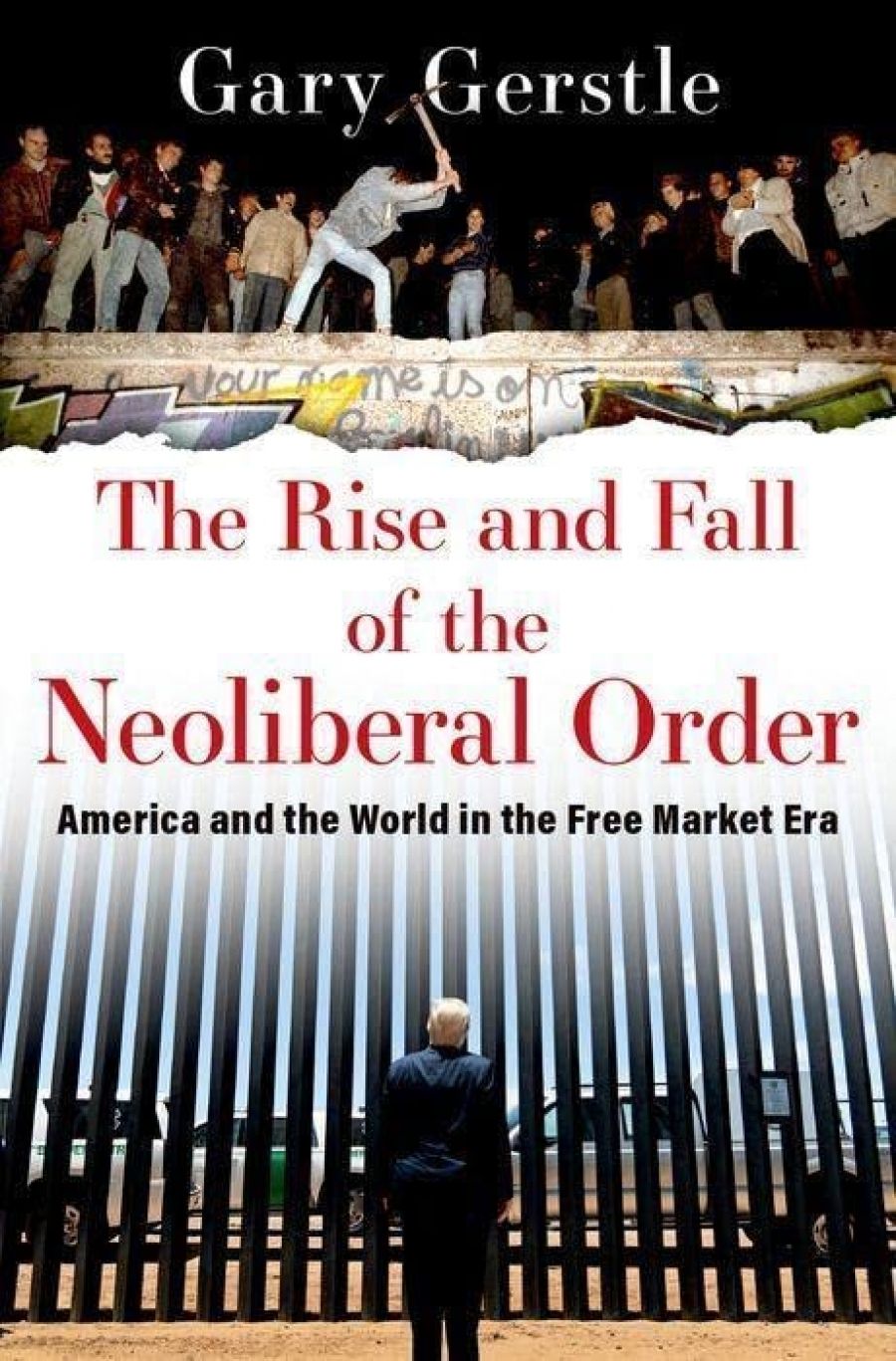

American presidential elections can be frustrating for outsiders. Non-Americans can’t vote, but humanity’s future may depend upon a few votes in a handful of gerrymandered states. I spent much of 2020 driving myself to distraction over the possibility that Donald Trump might be re-elected. I had no such anxiety in 2016: in my opinion, Hillary Clinton did not deserve to win. She personified too many of the failings of what Gary Gerstle (Paul Mellon Professor of American History at the University of Cambridge) has termed the neo-liberal order. Absent Bernie Sanders, I might have voted for Trump myself, had I been a US citizen. Four years on, I believed that foreigners deserved to be able to help unseat Trump. His presidency, as Gerstle explains in his new book, The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order, was the product of the socioeconomic mayhem created by neo-liberalism – and evidence of its decline.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ian Tyrrell reviews 'The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the world in the free market era' by Gary Gerstle

- Book 1 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order

- Book 1 Subtitle: America and the world in the free market era

- Book 1 Biblio: Oxford University Press, $45.95 hb, 418 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-neoliberal-order-gary-gerstle/book/9780197519646.html

The New Deal’s success came from a Depression-era political compact in which the rights of unions, immigrants, and other ordinary people were made more secure by social welfare, government financial stimuli, and protective labour laws. Reflecting modern interpretations of the ‘Long New Deal’, this political order took more than a decade to achieve hegemony. Gerstle argues that it was international communism as a threat to the New Deal state that solidified its position and made the order bipartisan. This was a fundamentally secular order, with religion supplying only a marginal element in the grand compromises. As Gerstle shows, the Cold War crucially sustained government expansion and high taxes into the 1970s.

Those who seethed against the New Deal’s hegemony organised, through the Mont Perelin Society led by the European émigré economist Friedrich Hayek and through the related work of Milton Friedman, to resuscitate a free-market alternative. Its contemporary appellation as ‘conservative’ reflected the New Deal appropriation of the term ‘liberal’, but Gerstle calls this alternative ‘neoliberal’, as it built upon a proper understanding of classical liberalism resting on the notion that government must create a rules-based framework to protect individual citizens’ freedoms, especially property rights.

Gerstle shows how and why state power could be reconciled with these individualist positions. The state would not only create the environment to promote economic individualism but also guard against those who eroded society by abandoning self-control. The work of Gertrude Himmelfarb and others developed complementary ideas of neo-Victorian morality in civil society that would prevent liberalism from becoming atomistic, by promoting abstemious family values as society’s stabilising force. Moreover, law enforcement and mass incarceration, often seen as exemplary contradictions within neo-liberalism, were essential to its functioning. This meant, in effect, forcing people to conform by coercing them if they transgressed against the moral and property-based foundations of neo-liberal society. Internationally this approach sanctioned larger military expenditures so long as they combated the dreaded communism threatening the neo-liberal world.

Gerstle makes the essential point that neo-liberalism also had a progressive expression, stressing freedom from state restraint. This tension surfaced in the utopianism of the internet revolution as a borderless world, with predictions of endless individual freedom, and among earlier New Left critics of the managerial or corporate state, in which business and government had entered into cosy and inefficient cooperation in need of disruption by anti-statism. Ronald Reagan spearheaded the political charge for individual freedom, but Gerstle correctly emphasises the Democrats’ Bill Clinton as the major agent of neo-liberalism’s apogee, thus demonstrating its consolidation as a political order.

The neo-liberal order’s triumph in the 1990s benefited enormously from the Cold War’s end and communism’s collapse courtesy of Mikhail Gorbachev. As Gerstle emphasises, Gorbachev chose not to use force to maintain the Soviet Union, in contrast to the way the Chinese leadership handled the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. Thereafter, with communism’s extinction in the Soviet Union, the incentive to incorporate workers in the social order not only in the United States but also in Europe declined and progressive trade unions and socialist parties gradually lost influence or turned neo-liberal. Moreover, the liberal ascendancy benefited from vast opportunities that opened up for new markets and the penetration of foreign capital in eastern Europe and Russia. The neo-liberal hubris that followed might well have been termed a hyper-charged version of US exceptionalism.

The book’s subtitle, America and the world in the free market era, is partly justified by astute attention to the Soviet Union’s fate, but this is still a US-centred account. The history of international neo-liberalism has been covered better by authors such as David Harvey in A Brief History of Neoliberalism (OUP, 2007). This Gerstle acknowledges early in the book. In the triumph of the neo-liberal order, ‘the world’ appears mostly through geopolitical shifts and the roadblocks to US neo-liberalism’s continued prosperity arising from the Iraq and Afghan wars and their aftermath. Here, I would argue, the US empire defined the limits and contradictions of neo-liberal freedom. The decline of that order is seen in the US manifestations of the global financial crisis and the inability of Barack Obama to deal with the fallout, as he clung to neo-liberal principles and, in effect, passed the leadership to Hillary Clinton for the unanticipated victory of the showman Trump. Gerstle explains Trump’s rise and why his impact was such an unmitigated disaster, leaving neo-liberalism in intellectual and perhaps political tatters.

As Gerstle states, no clear alternative for the future exists. Neo-liberalism might just hobble along. But it would make sense to recognise its structural determinants. Neo-liberalism’s US failures are those of a world ‘empire’, and empires don’t go down without a fight. As the current situation with – and growing enmity towards – the chief geopolitical rival China shows, the fall of the US version is unlikely to be pleasant for the rest of the world.

Another US-centred sign is treating climate change in five lines on the future. The solution to global warming does involve market controls to reverse neo-liberal influences. As climate change was clear enough at neo-liberalism’s apex over two decades ago, this probably inadvertent lacuna in Gerstle’s argument indicates how the United States as a whole has underemphasised the roots of this systemic challenge to the very survival of humanity. Neo-liberal deregulation of the global and US economies has been the key accelerator of climate change since the 1980s, through the extraordinary explosion of tourism, consumerism, global trade, and consequent fossil fuel emissions.

Even as neo-liberalism faces increasing political and economic challenges both within and outside the United States, current world events might not indicate neo-liberalism’s global ‘fall’. Instead, the international neo-liberal order might indeed strengthen. That aside, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the rallying of anti-Putin Europeans behind the ‘rules-based order’, aka the international neo-liberalism generated formerly by the United States, has exposed a deeper cultural hegemony of neo-liberal values in Western Europe and across the global Anglosphere. Those values may be detached from US dominance to assemble a new, more genuinely international order. But the United States would first have to stop acting not only as a neo-liberal order but also as a global empire.

Comments powered by CComment