- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Advances

- Custom Article Title: News from <em>ABR</em>

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: News from <em>ABR</em>

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

ABR was one of the original tenants when the Boyd Community Hub opened to much fanfare in 2012. From lion dancing to African drums to an adult-size Elmo, it was an occasion to remember as the magazine started a new chapter south of the Yarra. After the official opening, attendees filed up the staircase to our office, where they were treated to further festivities: a welcome from Editor Peter Rose and readings by ABR notables, including Lisa Gorton, Chris Wallace-Crabbe, and Rodney Hall. Over the years, such festivities have become a familiar sight at Boyd, with events ranging from ABR prize ceremonies to Shakespeare Sonnetathons to a memorable conversation between Gerald Murnane and Andy Griffiths downstairs in the Southbank Library.

- Square Image (435px * 430px):

Tracy Ellis wins the Jolley Prize

Sydney writer Tracy Ellis is the winner of the 2022 ABR Elizabeth Jolley Short Story Prize for her story ‘Natural Wonder’. From an overall field of 1,338 entries, she was named the overall winner at an online ceremony on 11 August. Ellis receives $6,000 from ABR. This year’s judges (Amy Baillieu, Melinda Harvey, and John Kinsella) described ‘Natural Wonder’ as having ‘a gently melancholic undertow … The story is remarkable for its quietness, acknowledgment of knotty feelings, and the room it makes for small miracles.’ (The judges’ full report, and a list of the longlisted authors, is available on our website.)

Nina Cullen was placed second ($4,000) for her story ‘Dog Park’; and C.J. Garrow, a former runner-up, was placed third ($2,500) for ‘Whale Fall’.

Our three winners read their stories in a recent episode of the ABR Podcast.

We look forward to offering the Jolley Prize for the fourteenth time in 2023.

As always, we thank our chief Patron Ian Dickson AM for his continuing and most generous support.

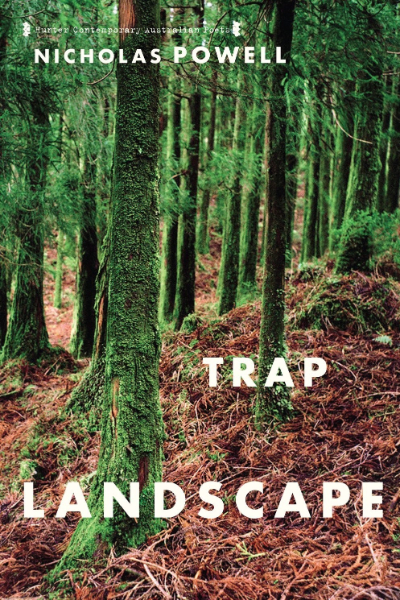

Contemporary takes

Given the paucity of new literary monographs in this country, it’s with some relief that we welcome the creation of Contemporary Australian Writers, a new series from the Miegunyah Press. Melbourne University Press will publish two titles each year. The series editor is Melinda Harvey, of Monash University. Nathan Hollier, Publisher and CEO of MUP, told Advances:

I still think there is a great value in talking about literature and what it says about our worlds, because creative writers can say things about those worlds that other writers can’t; they can represent the complexity of the world in a way that other forms of writing and other artforms can’t.

First up is the emphatically titled Lohrey, a needed study of the author of Camille’s Bread, The Philosopher’s Doll, and The Labyrinth, winner of the 2021 Miles Franklin Literary Award.

Coming titles in the series include Tanya Dalziell on Joan London and Emmett Stinson on Gerald Murnane – just in time for his Nobelisation perhaps?

A new environmental festival

Regional festivals often prove more intimate and congenial than boisterous metropolitan ones, and it’s hard to think of a more atmospheric setting for Australia’s newest one: the Mountain Writers Festival, which will run from 4 to 6 November 2022 in Macedon. MWF (though we doubt that will catch on without some contestation from the older festival down the Calder Freeway) was twice delayed because of Covid, but it arrives in confident shape, with an impressive line-up.

The organisers state that this will be ‘the first Australian writers’ festival to focus exclusively on the environment – the most important topic of our times – with a forever theme of “Place, Story, Nature”’. Speakers will include Evelyn Araluen, Claire G. Coleman, Tim Flannery, Declan Fry, and Anna Krien.

ABR, with its keen interest in these subjects, is pleased to be a sponsor of the festival. Historian Billy Griffiths (Deputy Chair of ABR and Macedon resident) will chair the ‘Trouble in the Outback’ panel on 6 November, with panellists Kate Holden, Joshua Kemp, and Tyson Yunkaporta.

The Festival will take place, mostly, at the capacious Jubilee Hall in Macedon. Early bird weekend and day passes go on sale on 5 September; single session tickets will follow on 20 September. Visit https://mountainwritersfestival.com.au

Staff changes at ABR

James Jiang left ABR in late August after sixteen months with the magazine as the ABR/JNI Editorial Cadet and Assistant Editor. We wish James well in his new role at Griffith Review.

We’re delighted to welcome Dr Georgina Arnott, who has joined ABR as Assistant Editor. Georgina, an author and academic, first wrote for the magazine in 2006. She is the author of The Unknown Judith Wright (2016) and Judith Wright: Selected writings (2022). Recently she undertook a year-long ABC Top 5 Humanities media residency. Readers will recall her illuminating August 2020 cover feature ‘Links in the Chain: Legacies of British slavery in Australia’.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

_Credit%20%E2%80%93%20Alana%20Holmberg%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)

%20(1)%20copy.jpg)

MitchOsborne%20(1)%20copy.jpg)