- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

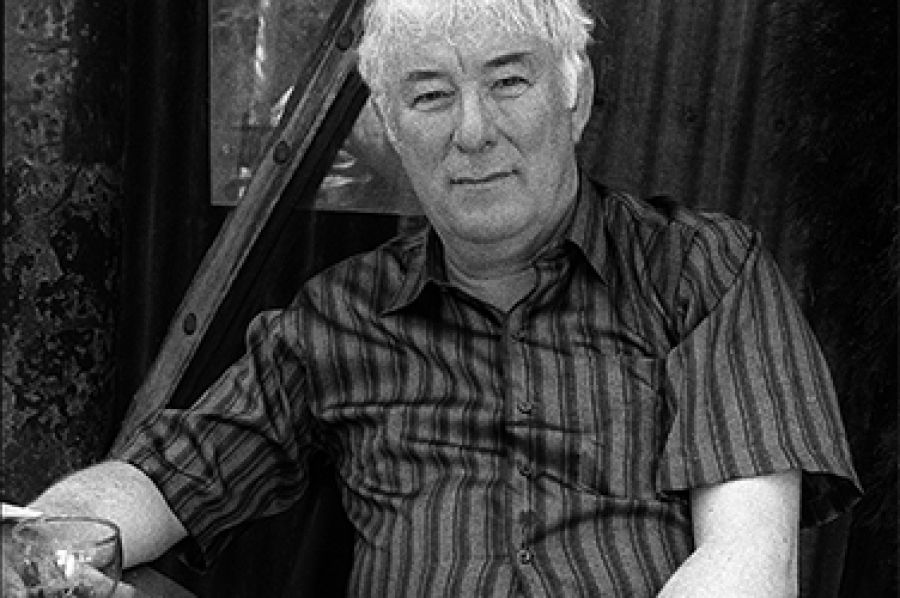

- Custom Article Title: ‘The verity of his company’: Seamus Heaney in Australia

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘The verity of his company’

- Article Subtitle: Seamus Heaney in Australia

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Think of Nobel Laureate Seamus Heaney and you mightn’t automatically think of Australia. What the name invokes for most readers, I would hazard, are the vivid landscapes of Ireland (‘The cold smell of potato mould, the squelch and slap / of soggy peat’). Heaney (1939–2013) might have been a man of the world, but he was rooted half a world away.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Seamus Heaney, 1994 (Juno Gemes)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Seamus Heaney, 1994 (Juno Gemes)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): '"The verity of his company": Seamus Heaney in Australia' by Tara McEvoy

To Irish eyes, the landscape bore the mark of unreality: palm trees lining the promenades, possums peering out from gum trees, those rows upon rows of Victorian houses with their verandahs, their ornamented parapets. I’d never before seen an Australian Magpie, a Myna, or a Fairywren; I googled their names frantically on my phone as they flitted by me in the streets (‘Australian Birds’, ‘Birds in Melbourne’). At home, it was the peak of summer, one of the hottest on record, but here it was ‘Christmas in July’: mulled wine and gingerbread hawked from carts; fake snow pumped out of machines. As Melbourne was waking up, my friends and family were going to the pub or going to bed. Heaney had visited the city once, in the mid-1990s, and I would wonder, as I walked around (from Newman College to the State Library, down Swanston Street; around Princes Park or Carlton or Brunswick), what he must have thought of it then.

Through the tight-knit Irish studies community in Melbourne (and largely thanks to the generosity of Dr Val Noone), I began to get some sense of Heaney’s relationship to Australia, the broad brushstrokes. In the archive at the St Mary’s and Newman College Academic Centre, I came across one of the earliest Australian critical engagements with Heaney’s work: an MA thesis by Helen O’Shea, under the tutelage of Vincent Buckley. She had submitted the thesis to the University of Melbourne in 1980. By this stage, Heaney had published five collections: Death of a Naturalist (1966), Door into the Dark (1969), Wintering Out (1972), North (1975), and Field Work (1979). Internationally, his star was rising. Helen later told me: ‘I first encountered Heaney’s work in 1977, when a friend lent me a copy of Death of a Naturalist. I had begun a part-time research MA on William Blake’s poetry, but immediately decided to change topics. I was enchanted by Heaney’s work.’ Further, she told me that during a research trip to Ireland, the Heaneys (Seamus and his wife, Marie) had become to her ‘a kind of surrogate family. They welcomed me into their home and from January 1979 I and Marie Heaney’s sister minded their Dublin house while they spent spring semester in Boston, during Seamus’s first appointment at Harvard.’ An interview with Seamus Heaney, conducted during Helen’s time in Ireland, appeared in Quadrant in 1981.

With an Australian minding their house in Dublin, the Heaneys forged a friendship with another Australian couple in Massachusetts: Peter Gebhardt, a teacher from South Australia (later a renowned judge) who had gone back to study at Harvard and wound up in Heaney’s classes, and his wife, Christina. Peter would later commemorate the period in a poem, ‘Seamus Heaney’s Poetry Workshop’: ‘So I went away and began / To do what he had called me to do, / Seize the word and make palpable / The lives and lines we take ...’ Other connections emerged. I learned of a number of significant poetic cross-currents between Ireland and Australia, beginning in the 1970s and continuing right up until Heaney’s death.

Some examples: in 1978, Rosemary Wighton extended an invitation to Heaney to travel to Australia and participate in the Adelaide Festival; Heaney initially accepted but, as the pressure of numerous other commitments mounted, he withdrew (stating, in a letter to Wighton, ‘The chance to visit Australia probably only comes once, and I did not withdraw lightly.’) In 1980, Heaney contributed a long piece on A.D. Hope to the London Review of Books, in which he revealed his broader knowledge of, and deep engagement with, Australian poetry: ‘Australian poetry is stronger now than it has ever been, and talking to Australian poets one gets an impression of renewed confidence in their separate, even separatist, enterprise.’ (He later selected Hope for inclusion in an anthology he co-edited with Ted Hughes, The Rattle Bag (2005), another sign of his admiration.)

In 1981, the Irish-Australian literary critic D.J. O’Hearn wrote on Heaney for the first issue of Scripsi, the influential journal published from the University of Melbourne. Peter Steele, a poet and academic who resided at Newman College, wrote extensively on Heaney’s work, and dedicated the poem ‘Horse’ to his Irish friend. A cursory perusal of the ABR archive revealed that it was littered with references to the poet, and a Google search for ‘Seamus Heaney and Robert Adamson’ threw up an early 2000s photo of both writers, alongside the photographer Juno Gemes, in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin. As you can see, links proliferated.

Perhaps Heaney’s most significant ties to Australia, however, came in the form of his friendships with three Australian poets: Vincent Buckley, Les Murray, and Chris Wallace-Crabbe. Heaney met Buckley in 1973, at the Yeats Summer School in Sligo; Murray at Rotterdam Poetry Festival in 1977; and Wallace-Crabbe in 1987, when he joined Heaney on the staff at Harvard as Visiting Professor of Australian Studies. Each of them stayed on friendly terms with Heaney after their first meetings. Heaney and Buckley spent further time together in Ireland, along with Buckley’s wife Penelope, and kept up a correspondence – selected letters are now housed in the archives of UNSW Canberra. In a letter to Penelope after Vincent’s death in 1988, Heaney wrote, ‘I loved the verity of his company, and always felt that his approval was worth more than most clamours of reputation.’ Heaney saw Murray occasionally at professional events over the years, and later championed him as ‘very much a presence’ on his imaginative landscape, ‘one of the “ironic points of light”’. Murray’s work, Heaney noted, was ‘original, obstinate, word-hoarding, wild-ranging, regenerate’. He stayed close, too, with Wallace-Crabbe, who later acted as a guide for Heaney when he visited Melbourne. Wildly different in terms of poetics, politics, and personality, each of these three men would nonetheless have some marked influence on their Irish contemporary.

Seamus Heaney and Vincent Buckley, 1977 (photograph by Marie Heaney)

Seamus Heaney and Vincent Buckley, 1977 (photograph by Marie Heaney)

Heaney was fond of – and often quoted – one Buckley line in particular: ‘Language is an entry into further language’. (As the critic John Dennison notes, ‘the formulation coincides neatly with his stress on possible pluralistic futures embedded in linguistic origins’.) The line applied to those discussions I had about Heaney during my visit to Melbourne: reminiscences were entries into further reminiscences, anecdotes entries into further anecdotes. Everyone I met, it seemed, had a Heaney story to tell. When the poet Joel Deane introduced me to the editor of this very magazine, I was delighted to find that he, too, had a Heaney connection. Peter Rose showed me a page from his 1994 journal. Heaney was here as a guest of the Melbourne Writers Festival. Rose sat next to him during the Victorian Premier’s Awards dinner:

Kevin Hart came and we talked about John Ashbery. Heaney compared him brilliantly with Swinburne, saying that Ashbery writes a kind of pure poetry. I told Kevin he would have to write the monograph. Heaney’s admiration for Ashbery has increased in recent years. He likes the way he conducts himself, without nonsense or grandiosity.

At the Festival, Heaney appeared in conversation with Wallace-Crabbe at the Merlyn Theatre; on the panel ‘God Moves in Mysterious Metres’ with Robert Gray, Gwen Harwood, and Kevin Hart, also at the Merlyn (the panel was recorded, with clips broadcast on ABC Radio, and later transcribed and published in Eureka Street); and in conversation with Edna O’Brien at the Town Hall. He was interviewed by fellow Irish poet Louis de Paor (then resident in Melbourne) for 3CR, and the interview was subsequently published in the fourth issue of the journal RePublica. He gave an interview to The Age, in which he spoke about his uncle, who had migrated to Australia in the late 1920s; the Australian poets he had read (Harwood, Hope, Judith Wright, Kenneth Slessor, and Rosemary Dobson) and those he’d met (Buckley, Murray, Wallace-Crabbe, O’Hearn, and Evan Jones). Gebhardt accompanied him to the bookshop Collected Works and later wrote a poem about the excursion (‘You were comfortable, at ease among the rows of books, / All friends of yours, going back for years. / And yours, like the “Glanmore Sonnets” / Were welcomed into the company of shelves with cheers.’)

Heaney made it out of Melbourne, too – to Queensland, and to Hobart, where he delivered the 1994 James McAuley Memorial Lecture (‘Speranza in Reading: On “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”’) at the University of Tasmania. In Melbourne, everyone I spoke to about Heaney’s visit to Australia remembered the occasion with great fondness; everyone commented on his humility and benevolence, in addition to his brilliance.

One year after his trip, Heaney received the Nobel Prize for Literature. This happy news was cause for celebration in Melbourne, with an event at the Old Colonial Inn on Brunswick Street including tributes from several locals: among them Gebhardt; Penelope Buckley; Wallace-Crabbe; de Paor; the comedian Mary Kenneally (another former student of Vincent Buckley’s); a schoolmate of Heaney’s, Paddy Donnelly; satirist John Clarke; and the broadcaster Ramona Koval. In 2013, on Heaney’s death, there was once again an outpouring of emotion in Australia. The University of Western Australia hosted an event commemorating the poet’s life; obituaries were published in The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald among a range of other Australian publications. In the Australian Senate, on 12 November, Wicklow-born Senator Ursula Stephens of the Australian Labor Party paid tribute to Heaney, reminiscing about her friendship with the poet and his memories of Australia and perspectives on the country’s politics: ‘In 2008 on a visit to Ireland I spent a lovely afternoon with Seamus and Marie at their cottage in Wicklow […] He talked about coming back to Australia – he had been here in the 1990s – and about how pleased he was by our apology to the stolen generations. It struck him as justice that had waited a long time to be served.’ Two days later, a motion proposed by Stephens – to formally acknowledge Heaney’s importance to Australia and to ensure that the country offered its respects – was passed by the Senate.

Heaney’s last collection, Human Chain, had been published a couple of years before his death, in 2011, but he continued to write individual poems until the end of his life, poems that remain uncollected. One such work is ‘A Section’, the poem which Heaney contributed to Travelling Without Gods: A Chris Wallace-Crabbe companion, produced to celebrate Wallace-Crabbe’s eightieth birthday. The book was published in 2014, after Heaney passed away (in August 2013); as its editor, Cassandra Atherton, notes in the book’s introduction, Heaney’s poem ‘may well have been one of the last he wrote before his death’. It is also notable for being one of very few poems in which Heaney directly discusses Australia:

A section of sugar cane,

a trim short stick I found

in Queensland on cleared groundwhere my letter-writing uncle –

a good hand, stubber of stumps –

wrought in the 1920sa bit of sunburnt stalk,

a flute with its stops all blocked,

I would raise it even soand set it to my lips …

In Melbourne, I strained to hear the echo of this music: a generation later, ten thousand miles from home. How had Heaney’s words reverberated here? Heaney may have spent his life writing about Ireland, but his themes were universal, and his global footprint sizeable. His poetry, it turned out, had resounded in Australia, and it was resounding still.

This article, one of a series of ABR commentaries addressing cultural and political subjects, was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment