- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Serious matters

- Article Subtitle: Two recent medical thrillers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

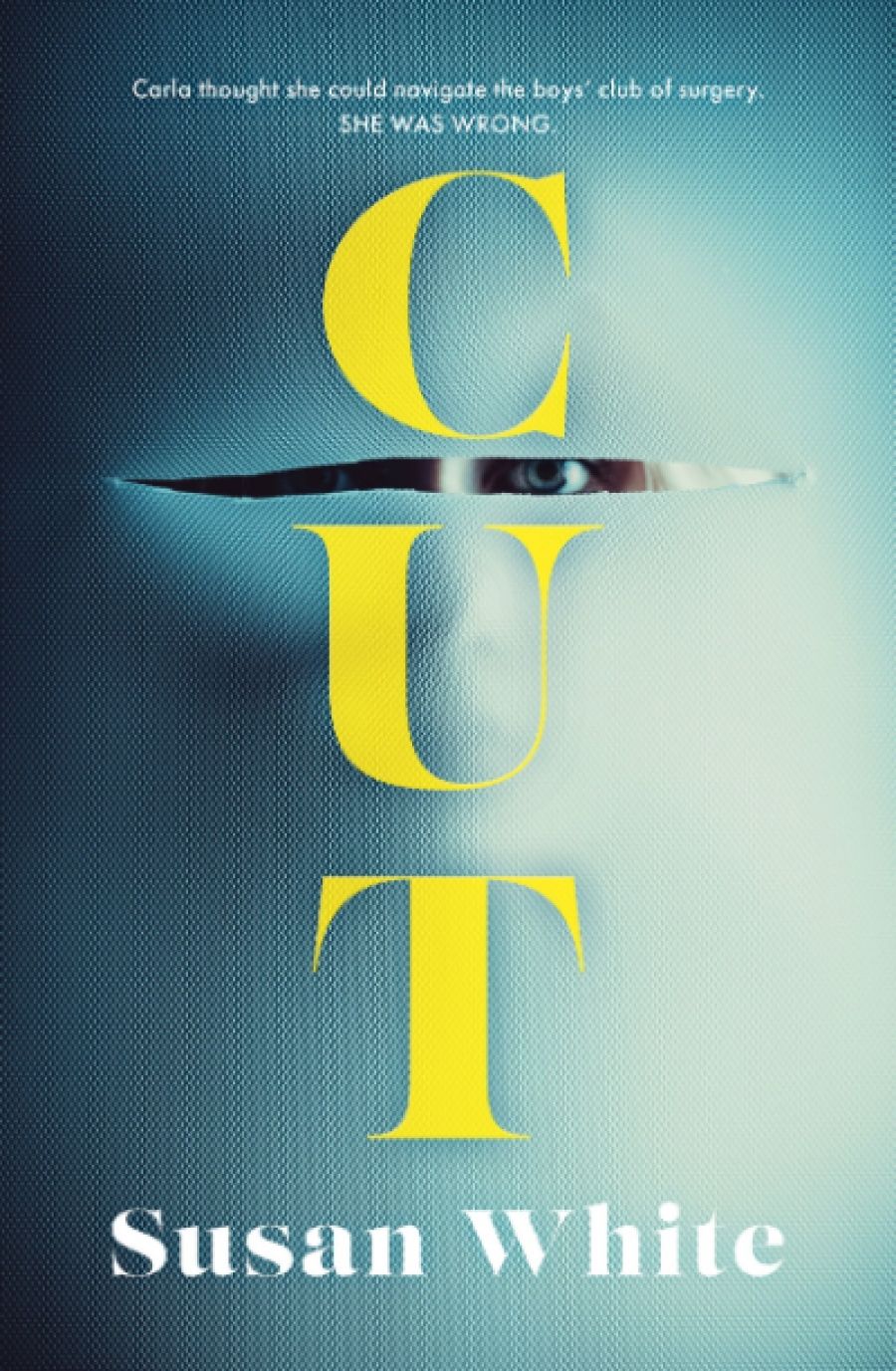

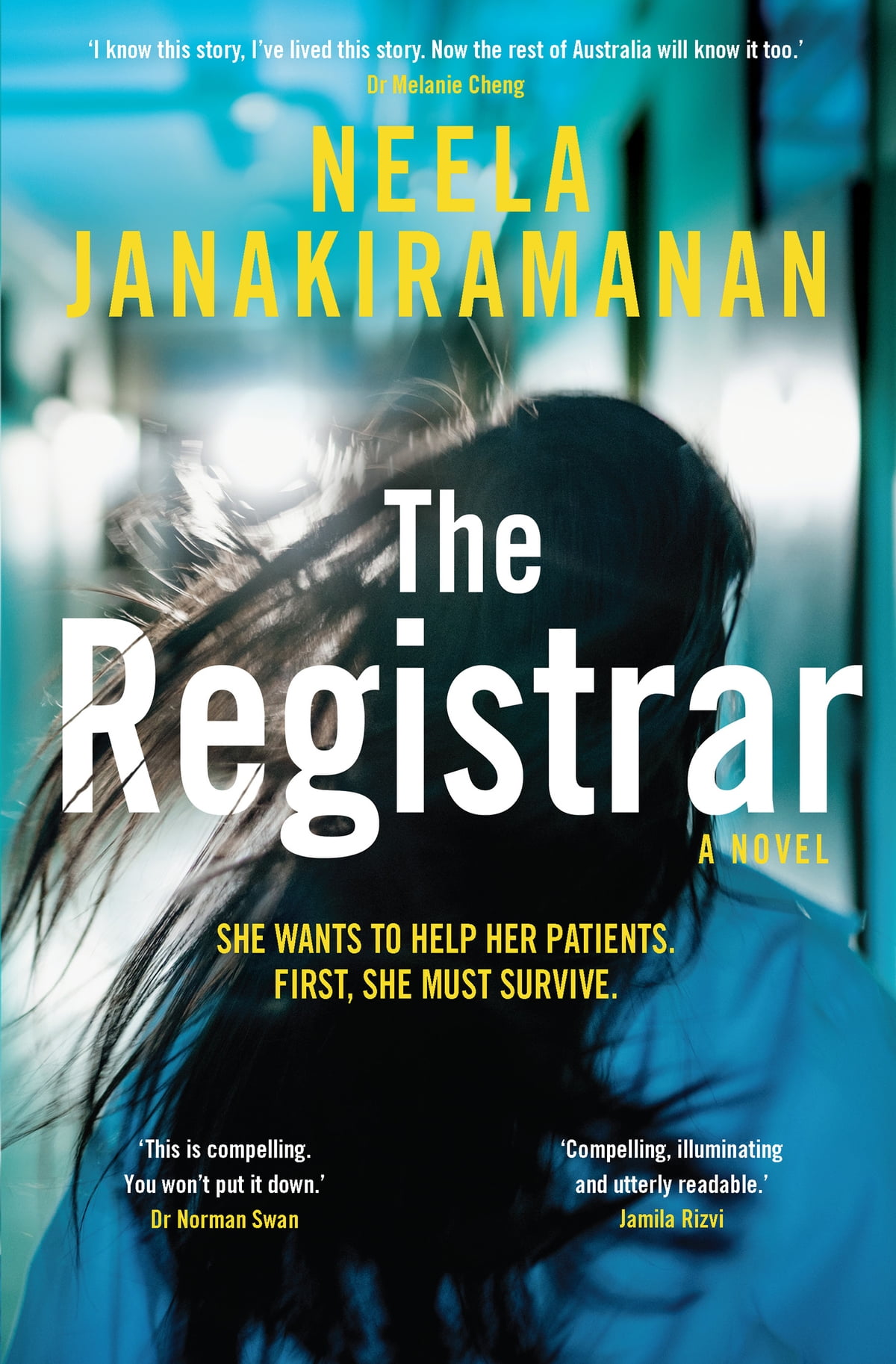

It can only be coincidence that two very similar novels have been produced by contemporary doctors, but the overlapping characters and themes of Cut and The Registrar are so striking that it’s hard not to visualise their authors, Susan White and Neela Janakiramanan, getting together somewhere to sketch out their early drafts. Both novels feature young female protagonists working in teaching hospitals, who are as dedicated to their patients as they are to advancing their careers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Debra Adelaide reviews 'Cut' by Susan White and 'The Registrar' by 'The Registrar' by Neela Janakiramanan

- Book 1 Title: Cut

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $32.99 pb, 328 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/zaV7BW

- Book 2 Title: The Registrar

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin $32.99 pb, 357 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/yRNmjy

Cut’s Carla di Pieta and The Registrar’s Emma Swann are also subjected to punishing work schedules and a patriarchal

misogyny that occasions sexual and other forms of predation. Each novel also includes highly detailed descriptions of hospital and surgical procedures, health conditions, and other medical matters, sometimes possibly too technically precise for the general reader (though the frustrated surgeon in me was fascinated).

Obviously, personal experience has inspired and informed both novels. One can see the writers’ festival panels assembling already. Perhaps these authors have written their books to expose a fractured system, or perhaps they have just identified a good story. Either way, it’s true that popular critical reception of so-called issues-based fiction always focuses on the themes in common, to the extent that the novels themselves are rarely evaluated as novels. More on that shortly.

Both stories deal in urgent and serious matters, at the heart of which are exploitation, sexual assault, and bullying on a major scale. Each of these protagonists is oppressed and abused by the same system they paradoxically yearn to enter. Fierce ambition (albeit coupled with self-doubt) and conflicting experiences lead them to some foolish choices, desperate actions, and, ultimately, painful self-recrimination. If these novels are designed to reveal the truth about the hospital system that devours its best and brightest young trainees then they could hardly have done a better job – any prospective medical trainee, female or not, reading Cut or The Registrar would surely reconsider their career choice, so savage are their portrayals of the abuse of power – but let us proceed on the basis that these are primarily works of fiction.

Cut’s Carla is a mix of vulnerability, innocence, ambition, and ruthlessness. Fellow surgical trainee and secret lover Toby is her ‘dream man – beautiful, clever and with a sureness about him’. Carla allows herself to be distracted and compromised by him at work just before an operation, a brief encounter that initiates a series of events with near-fatal consequences for the patient. Even so, she takes a long time to shake off the odious Toby, only doing so when she sees how deeply invested he is in the boys’ network she is up against.

Susan White (photograph by Marcel Aucar)

Susan White (photograph by Marcel Aucar)

This covert relationship is the spine of the story and as such represents all its strengths and weaknesses. On the one hand, it is a romance to the point of cliché: in one scene, Carla’s heart supposedly skips a beat (and these people are doctors!) when Toby hands her a gift she secretly hopes is a ring. The flaws and imbalance in this relationship flash red lights from the start yet remain unnoticed by the highly intelligent Carla, while Toby himself is too flat and stereotypical to be convincing. On the other hand, the relationship symbolises the perversion of power played out on a wider scale in the novel’s overall project to expose misogyny on the cusp of the global #MeToo movement. Here the young, the female, and in Carla’s case the physically small, junior doctor is perpetually judged by a supposedly objective standard. Her formal complaint to the hospital about two male doctors exercising inordinate powers and either perpetrating or condoning behaviour from the casually sexist to outright sexual abuse seems to be backfiring, but at the end a more resilient and confident Carla soberly makes her way back to the surgical career she loves. Doubtless the story is not so positive in the real hospital world.

Clichés like hearts skipping beats along with problematic villains and stiff, wordy dialogue detract from Cut’s obvious merits. These include an imaginative structure offering short flashbacks to the incident leading to Carla’s breakdown, alternating with chapters named with medical terms that are both poetical and in context sometimes ironic – ‘poor historian’, ‘debridement’, ‘evisceration’, and so on. The Registrar, by contrast, offers a straightforward linear narrative and uses the present tense, which does not necessarily create immediacy, contrary to popular opinion, but risks flatness of expression. The novel also comes with endorsements from nearly a dozen doctors, all testifying to the story’s honesty and medical authenticity. Still, trying to concentrate on the novel as a novel, in which fictional authenticity is something quite different, I find a more compelling storyline, partly due to its less cluttered cast and sharper focus.

In the character of Emma Swann, whose speciality is orthopaedic surgery, once more we find a small female figure adrift in an indifferent to cruel hospital system. The bitter competitiveness and backstabbing among Emma’s colleagues are downright pleasant compared with the structural and personal impediments to the progress of her career. While we all know doctors are not deities, despite the universal reverence accorded them, unfortunately the villains here are also two-dimensional. Emma’s own flaws include a stubborn blindness to flattery from a senior surgeon whose oily manipulation practically oozes from the page. When she eventually submits to her abuser, she tells herself that not only is she unable to reject ‘love and validation, whatever form they take’, but that he has made her ‘feel clever and important and understood in a way no one else has’. This is so not believable: she is, after all, the wife of an adoring and supportive man, the high-achieving daughter of a loving mother (although her father is a driven, callous former surgeon), and the sister to a devoted and helpful older brother whose own story provides another central crisis of near-tragic dimensions. Maybe Emma would succumb to this sexual predator, but for other reasons. Or maybe she simply should explain herself less.

However, The Registrar offers several unexpected twists and revelations, meaning Emma’s own prejudices and ambition-led assumptions are eventually exposed. These include revising her opinions of other doctors whose humanity and compassion offer some humbling lessons before the novel’s end. A confrontation with her ridiculously pompous father is also very satisfying.

Interestingly, neither novel references the greatest health crisis of our time. In the case of Cut, this is due to the story having been written before 2019, while in The Registrar no time is specified. There may be practical reasons for this, yet both books have been published well after the initial pandemic and have still resisted its impact. Perhaps Covid-19 offers such creative and formal challenges that it requires more processing before it can successfully be represented in fiction. If so, then doctor–novelists are just as doubtful and unconfident as ordinary ones.

Comments powered by CComment