- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Weaving and brewing

- Article Subtitle: A lifetime of bookish immersion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On 1985, the American poet and essayist Susan Howe deftly jettisoned any pretensions to objectivity in the field of literary analysis with her ground-breaking critical work My Emily Dickinson. The possessive pronoun in Howe’s title says it all: when a writer’s work goes out to its readers, it reignites in any number of imaginative and emotional contexts. What rich and varied screens we project onto everything we read.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gregory Day reviews 'Telltale: Reading writing remembering' by Carmel Bird

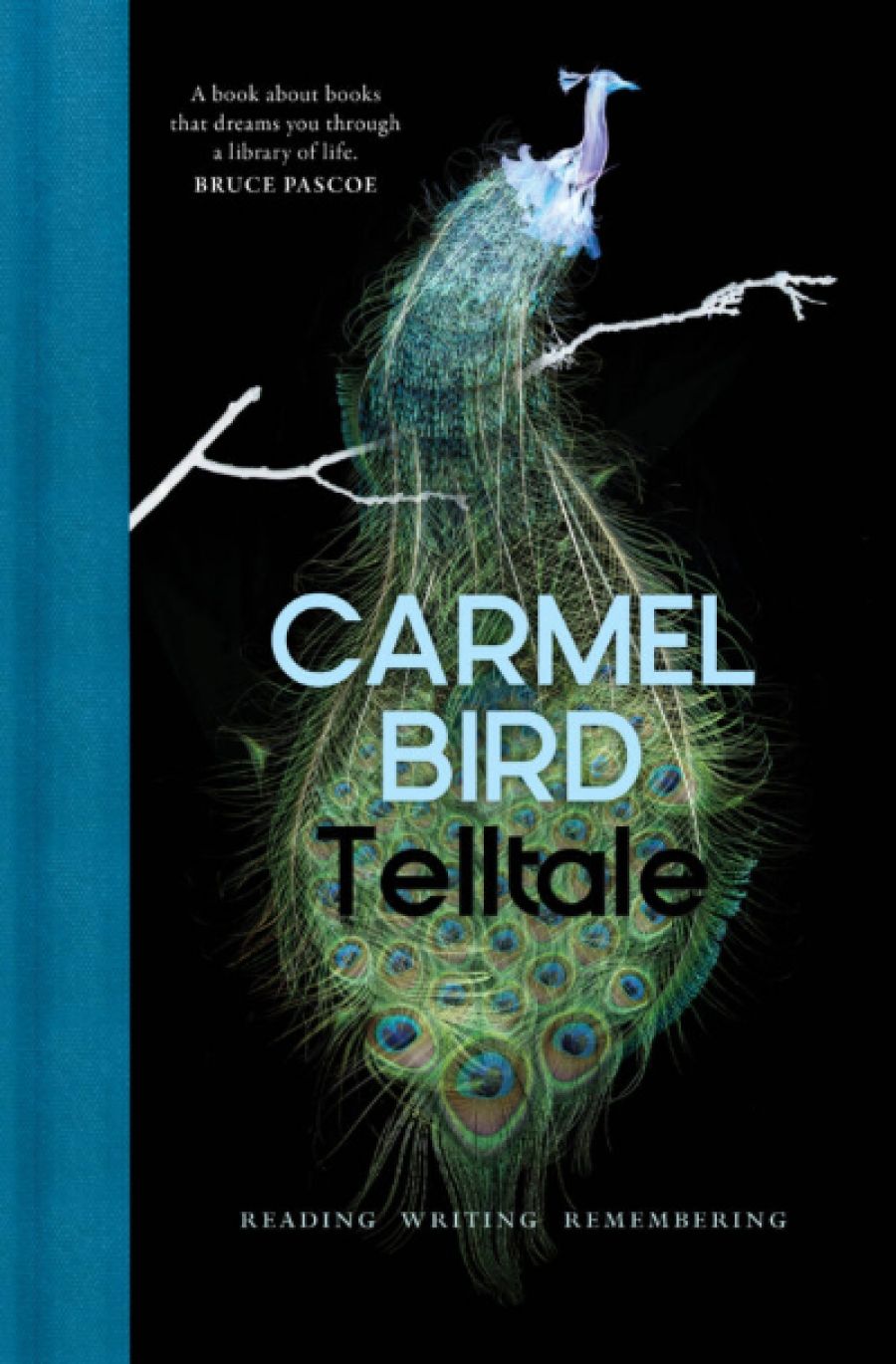

- Book 1 Title: Telltale

- Book 1 Subtitle: Reading writing remembering

- Book 1 Biblio: Transit Lounge, $32.99 hb, 274 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/jW0K9Z

Fast forward to 2020. Carmel Bird is locked down in what she calls ‘the great Covid enchantment’, confined to her home full of the objects of her life, including many, many books. With more time than usual to contemplate editions she hasn’t looked at for a long time, she rediscovers her library as a sanctuary of highly personal artefacts, an intimate archival site of the various selves she inhabited when she first read each volume: the joyful, intuitive girl of eerie 1940s Tasmania; the cosmopolitan student of French at the Sorbonne in the 1960s; the married writer living in Los Angeles in the 1980s; the prolific novelist and short story writer of renown here in Australia; author of Cherry Ripe (1985), Cape Grimm (2004), Field of Poppies (2019), and many other books. Detecting the spark of a fresh narrative method in the history of her reading, Bird decides to tackle the retrospective process head-on, to stalk her own past selves through the rooms of her library in order to discover ‘the story of the story’.

Carmel Bird (photograph via Transit Lounge)

Carmel Bird (photograph via Transit Lounge)

What ensues – Telltale: Reading writing remembering – has been described by Hilary McPhee as ‘a rare thing, an ingenious memoir’. The books in Bird’s library, in all their aromatic, tactile physicality, provide the impetus, but more than that it is the bridge between individual imagination and published text that shapes this superbly dialectical deep dive.

Fittingly, the chronicling of Bird’s reading life is framed by the motif of a bridge, the Kings Bridge at Cataract Gorge in Launceston, where she pictures herself, on 9 March 1945, as a young girl, going for a picnic with her family. Cataract Gorge is a landscape Bird has written about before, perhaps most notably in her tricksterish novel The Bluebird Café (1990), and here again she meditates on the idea of the trickster in literature, which she encounters for the first time via the character of Brer Rabbit in a ‘racially stereotyped’ wartime edition of Stories From Uncle Remus, given to her by her aunt as a birthday present. The copy is still on her shelves, easy to find ‘with a lot of other green books’. As she takes it down, the signature chiaroscuro that has defined so much of her writing once again takes flight. ‘How innocent children are in the hands of authors who teach and entertain them,’ Bird remarks, reflecting on her first reception of Uncle Remus and the facts she subsequently learnt about the sinister nature of its production. ‘I see the clear racial stereotype and prejudice now,’ she says, while noting that ‘the tales themselves are still alive and fascinating’.

This willingness to allow for alternative, contradictory, and co-existent perspectives is a feature of Telltale. It is particularly focused in the recurring flashback of that small child crossing the bridge with her family at Cataract Gorge. Bird braids the seemingly innocent prospect of a picnic in a park full of peacocks with the chthonic terror that possesses her as she crosses the ancient river. Dark atavistic rock is everywhere, the tragic silencing of local culture too. It is also the day when the United States will air-bomb Tokyo. Suddenly, even to the child, what appears peaceful – the picnic basket, the tollbooth, the prospect of the flamboyant peacock tail – seems the result of the decisive operations of a merciless power.

This kind of wrangling with Bird’s own enculturation via a lifetime of bookish immersion gives Telltale its layered and properly complex traction. As she proceeds randomly through her library, we encounter a range of voices, every one of which is determined by the evolving textures of her eclectic mind. In her love of fairytale we find a template of her vivid yet noirish aesthetic; in her appreciation of writers such as Vladimir Nabokov and W.G. Sebald we see the enthusiasms of the literary formalist. Accordingly, Telltale becomes a fine balancing act between Bird’s insouciant creativity and her intuitive thirst for truth and justice. Thus the stories accrue, as have the books, with each of them having at least two sides, just as the places of her childhood have at least two names. ‘I am mining and I am weaving and I am brewing’, she tells us, as her past comes alive again in her hands.

At the heart of Bird’s method is the time she takes to immerse us in the provenance of specific illusions she inherited in her youth about the brutal history of the island where she grew up – lutruwita – Tasmania – Van Diemen’s Land. She also admits the pleasure she takes in the cultural products of that self-same colonial empire she is native to. That she still delights in a variety of Edwardian-inflected aesthetics speaks honestly to how, for better or worse, a large portion of who we are is culturally determined, and therefore hybrid. Bird’s self-interrogating approach shows how any wholesale denial of inheritance is a thing to be wary of and in this way she stands as a mature and resolutely playful thinker about her own complex slice of human history.

It is clear that Bird’s Brer Rabbit would certainly not be the same as that of the African-American slaves whose stories it purports to tell. Likewise, the night sky of Bird’s Tasmania has peacock constellations along with emus, another numinous detail of the kind of hybrid haunting unleashed by the book-obsessed, bird-loving, violent British Empire. It’s what Telltale manages to do with such dark materials that makes it so engaging, especially right now, as Australia moves finally towards a more regenerative relationship with the country’s First Nations. And therein lies a key stimulus in Bird’s oeuvre, as well as here in the teeming reflections of Telltale. What claims to be singular is never so. One nation is actually hundreds, one book a universe, and a different universe in each person’s hands.

Comments powered by CComment