- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The construction of history

- Article Subtitle: Exploring the impact of colonialism

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

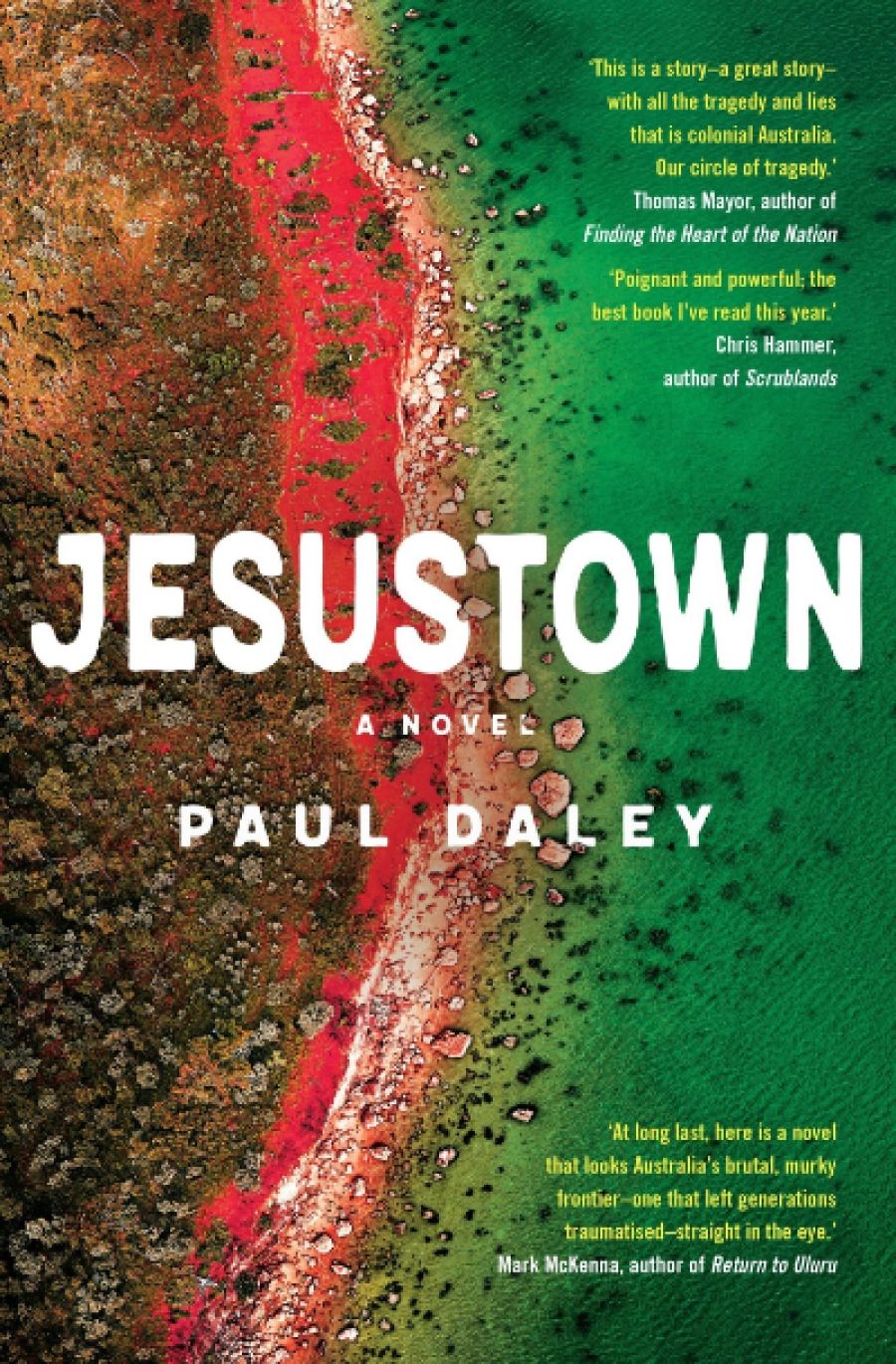

Paul Daley will be familiar to many readers as a respected journalist expressly committed to exposing the blind spots of white culture’s dominant myths about Indigenous history and Australia’s national identity. Daley is perhaps less well known as a novelist and playwright. These two interests in his work – historical research and imaginative writing – inform his powerful second novel, Jesustown, Daley’s seventh book, and one which he felt ‘compelled’ to write.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Midalia reviews 'Jesustown: A novel' by Paul Daley

- Book 1 Title: Jesustown

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 364 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/kjqmNV

The title Jesustown both refers to the name of a fictional former mission town in remote regional Queensland and serves as a symbol of Indigenous people’s suffering. Drawing on his wide reading of anthropologists, consultations with national museums, and extensive discussions with Aboriginal people, Daley has produced something akin to an Antipodean version of Heart of Darkness. Like Joseph Conrad’s novella, Jesustown uses a frame narrator and the structure of a literal and symbolic journey from England to Australia to reveal the horrors of colonialism. The novel’s ethical ‘heart’ is a fictionalised version of the collaboration during the 1930s and 1940s between Australian and American scientists, explorers, and adventurers in search of Indigenous cultural material. In the aftermath of Australia’s frontier battles and massacres, these expeditions involved the widespread theft of Indigenous art and the removal from traditional burial grounds of Aboriginal remains. These plunderers either saw themselves as noble chroniclers of the extinction of an uncivilised race or were simply keen to make money. Either way, as the novel insists, the thefts show white culture’s profound disrespect for the beliefs and practices, for the very humanity, of Indigenous people.

Jesustown is not only about history; it is also centrally concerned with the construction of history itself. While the novel uses a range of Indigenous voices, often to criticise white culture’s racism or hypocrisy, its narrative perspective is white. It’s an ethically circumspect decision by a non-Indigenous writer of fiction. The novel’s frame narrator, Patrick Renmark, an expat Australian living in London, is the author of bestselling works of historical biography. His books are designed to ‘make readers feel good about their myths and fables’ by deliberately erasing the ugly facts. He sees no need for his book on Lachlan Macquarie, for example, to mention the fact that Macquarie ‘stole native children from the sites of the massacres he’d ordered’. Patrick’s journey to enlightenment begins when, in flight from the scandal of an adulterous affair and the death of his young son, he reluctantly accepts a publishing deal to write the history of his renegade grandfather Nathaniel (Renny) Renmark. Patrick has long been aware of Renny’s legendary status as a man who lived harmoniously for years with the Indigenous people of Jesustown, but when he flies there to research Renny’s archives, he has no idea of the horrific stories he will discover.

Renny’s journals, photographs, and newspaper articles – the novel’s evidential texts – contain detailed and shocking accounts of the barbarity of white culture. He describes, for example, how the Reverend George Pyle locked Indigenous men in cages and left them to rot in their own filth. He describes savage beatings, systemic rapes, the chaining of Aboriginal people, appalling miscarriages of justice. But his archives, particularly his extensive audiotapes in which we hear his compassionate, angry, and sometimes boastful voice, also reveal his contradictions as a self-styled white saviour. Like several of the historical figures on which his character is loosely based, Renny is both dedicated to ‘saving’ the traditional culture of the Indigenous community and unwittingly complicit in the grievous damage suffered by the people he putatively respects. Renny is no Mr Kurtz – the atrocities are committed by men like Pyle or the aptly named, pathologically narcissistic Fergal Suckler – but his so-called good intentions have had disastrous consequences for those he calls The People. His tapes also, and importantly, express his belated admission of guilt and shame. This is history-as-confession and a rewriting of the self-serving myths of benevolence and progress on which white Australia is founded.

The two male narrators are also psychologically astute studies in a particular version of masculinity. Indifferent husbands and neglectful fathers who egotistically crave public recognition, they are both victims of emotionally stunted or abusive fathers. But the novel scrupulously avoids presenting this cycle of masculine dysfunction as commensurate with the intergenerational trauma experienced by Aboriginal people. Nor does it allow the men’s personal grievances to dominate the narrative or to have the last word. The story that must ultimately matter most is the exploitation and abuse to which Aboriginal people were subjected by a rapacious, uncivilised white culture. I suspect that many white readers will know little about the ubiquitous theft of Aboriginal art, skulls, and bones, the consequences of which are still being suffered by Aboriginal people today. As one such reader, I feel indebted to Daley’s novel for making this aspect of our history more widely known.

As a work that blends history and fiction, Jesustown is also highly readable. While overt political commentary sometimes intrudes into the narrative, the plot is absorbing, the writing stylistically assured. The novel creates a vivid sense of regional and urban spaces, and moves deftly from the sardonic to the melancholy, the visceral to the bitingly satiric. The dialogue is convincingly naturalistic and sometimes caustically, enjoyably humorous. The novel also cleverly combines Patrick’s self-lacerating flashbacks with the forward movement of his discoveries, propelling us to the final revelations and refusing white readers the convenience of moral absolution. Jesustown is an invaluable addition to Daley’s impressive body of work. It is also implicitly asks, as an urgent national issue, white culture to respect the integrity, sense of community, and desire for self-determination of First Nations people.

Comments powered by CComment