- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: The Museum of Mankind

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Museum of Mankind

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Algeria, June 1835. General Camille Alphonse Trézel’s expedition to pacify the western tribes had failed. Under the leadership of Emir Abdel Kader, Commander of the Faithful, the Algerians had bloodied the French invaders badly. Outnumbered and compelled to withdraw to the port of Arzew to resupply, Trézel’s column fought desperate rearguard actions for three days and nights. On the fourth day, the Algerian cavalrymen outflanked the exhausted French and were waiting in ambush on the edges of the Macta marshes.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 'The Museum of Mankind' by Michael Garbutt

Paris, 2020. The fluorescent lighting in the basement of the Musée de l’Homme, the Museum of Mankind, in the Place du Trocadéro, is less dramatic than the burning torches of Macta, but the 18,000 skulls under its cold white glow would make a far more impressive pyramid. Naturally, the Museum employs a storage method that avoids any hint of ‘promiscuous piling’. Each skull occupies its own hand-numbered cardboard box, neatly lined up with its neighbours on the multi-level rows of steel shelving that fill the Museum’s vast basement. On the front of each box, a transparent plastic window allows staff to see the contents at a glance.

The skulls come from many different parts of the world, united by the fact that at some point over the past three centuries they had the misfortune to come into contact with French civilisation. Some of these forlorn remains may finally be returned to their countries of origin. Researchers have established the identities of the contents of five hundred boxes, including those of thirty-six Algerians. Pending identification, the rest will remain in the basement. In response to concerns raised on social media, the manager of the collection is at pains to stress that the skulls and human heads (some retain hair and skin) are not on public display.

¥

The strength of the Museum’s commitment to preserving human dignity was demonstrated in June 1940. After Paris fell to the Germans, Paul Rivet, the Museum’s founding director, and his staff established le Réseau du Musée de l’Homme, the Museum of Mankind Network. It was the first organised group in France to resist Nazi occupation. The Museum Network set up escape lines for refugees, allied airmen, and prisoners of war. It also published the clandestine Résistance and Vérité Française newspapers, and supplied the British with military intelligence. By mid-1942, the Network had been shut down, betrayed by a double agent working for the Germans. Ten members of the Museum staff – seven men and three women – were sentenced to death. The men were executed by firing squad, the women deported to concentration camps.

The Nazis tortured, shot, or enslaved the staff at the Museum of Mankind, but they left the collection intact. Half a century later, President Jacques Chirac adopted the opposite strategy: he left the staff intact – completely ignored them in fact – but eviscerated the Museum’s collection of ethnographic artefacts. It was part of a long-overdue historical accounting. As Chirac explained in 2006 at the opening of the Musée du Quai Branly, where much of the Museum of Mankind’s collection had by then been relocated, ‘France wished to pay homage to peoples to whom, throughout the ages, history has all too often done violence’.

Chacapoya mummy at the Museum of Mankind (photograph by Velvet via Wikimedia Commons)

Chacapoya mummy at the Museum of Mankind (photograph by Velvet via Wikimedia Commons)

The president’s use of the word ‘history’ was adroit. It allowed him to avoid saying ‘France’ twice in the same sentence. Try replacing ‘history’ with ‘France’. It doesn’t sound as elegant. M. Chirac also explained who these peoples were to whom France wished to pay homage, and what ‘history’ had done to them:

Peoples injured and exterminated by the greed and brutality of conquerors. Peoples humiliated and scorned, denied even their own history. Peoples still now often marginalised, weakened, endangered by the inexorable advance of modernity. Peoples who want their dignity restored.

It was a powerful speech. The word ‘history’ also implied that the greed and brutality belonged to a distant past. President Chirac did not mention his own decision in 1995 to give the inexorable advance of modernity a nudge by resuming nuclear testing at Mururoa Atoll in French Polynesia.

The Quai Branly Museum was the president’s personal legacy project. Its mission to ‘study, preserve and promote non-European arts and civilisation’ would help restore the dignity of all those people to whom ‘history’ had done violence. The new museum was designed by French super-architect Jean Nouvel. ‘It is a building,’ M. Chirac noted with justifiable pride, ‘of masterful architecture, suffused with respect for the visitor, the environment, the works and the cultures that produced them.’

The artefacts installed at Quai Branly came from institutions where their cultures had not always enjoyed such respect. One was the National Museum of the Arts of Africa and Oceania, formerly known as the Museum of France Overseas, the supposedly permanent home of what had started out as the no-need-for-euphemisms Colonial Exhibition of 1931. The Museum achieved a final act of expiation for its colonial past by closing down and transferring its collection to Quai Branly.

The rest of the Quai Branly collection came from the Museum of Mankind, another institution that Chirac evidently decided should make amends for its past associations with the French colonial project. Perhaps it was the memory of the Museum’s heroic role in the Resistance that saved it from being completely shuttered. Its continuing existence also resolved the inconvenient question of what to do with the 18,000 skulls and other human remains, whose presence at Quai Branly would have jarred with the new museum’s mission to pay homage to peoples to whom, throughout the ages, history had all too often, etc. etc.

So the Museum of Mankind survived, but it faced an uncertain future. Most of its collection was gone and what remained largely consisted of unexhibitable body parts. A less resolute management might have despaired, but this was an institution whose staff had shown indomitable courage and resourcefulness in the face of Nazi terror. It would not be daunted by the challenge of reinventing itself merely because it had nothing to exhibit. The Museum closed its doors to the public and began a period of intense self-reflection, grappling with the three fundamental questions every organisation at a crossroads must address: Who are we? Where did we come from? Where are we headed?

After six long years of intense discussion, debate and stakeholder consultation, the Museum was able to give three unequivocal answers, and thus articulate its vision for the twenty-first century. The years of self-interrogation had not been wasted. As its website boldly states, the Museum’s mission is to address three important questions: Who are we? Where did we come from? Where are we headed?

It was a stroke of genius. ‘We’ no longer referred to the Museum of Mankind but to All Mankind. In 2015, the Museum finally reopened its doors to the public, revealing a €92 million renovation of its interior and a completely new exhibition design. The exhibits are divided into three sections: ‘Who are we?’ ‘Where did we come from?’ ‘Where are we headed?’

In ‘Who are we?’, visitors discover that we are human beings and that our scientific name is Homo sapiens. The key message of this section is that we are a species of great diversity, as illustrated by various images and busts on display. But in the end, we learn, there is far more that unites than divides us.

The answer to ‘Where do we come from?’ is that we evolved from proto-hominids, and other pre-human ancestors. From a curatorial perspective, the beauty of this section is that real skulls and bones from the Museum’s collection can be displayed and no one is going to complain about the indignity they suffer.

‘Where are we headed?’ is the most speculative section. Catastrophic climate change, nuclear holocaust, and universal peace and harmony are mooted options.

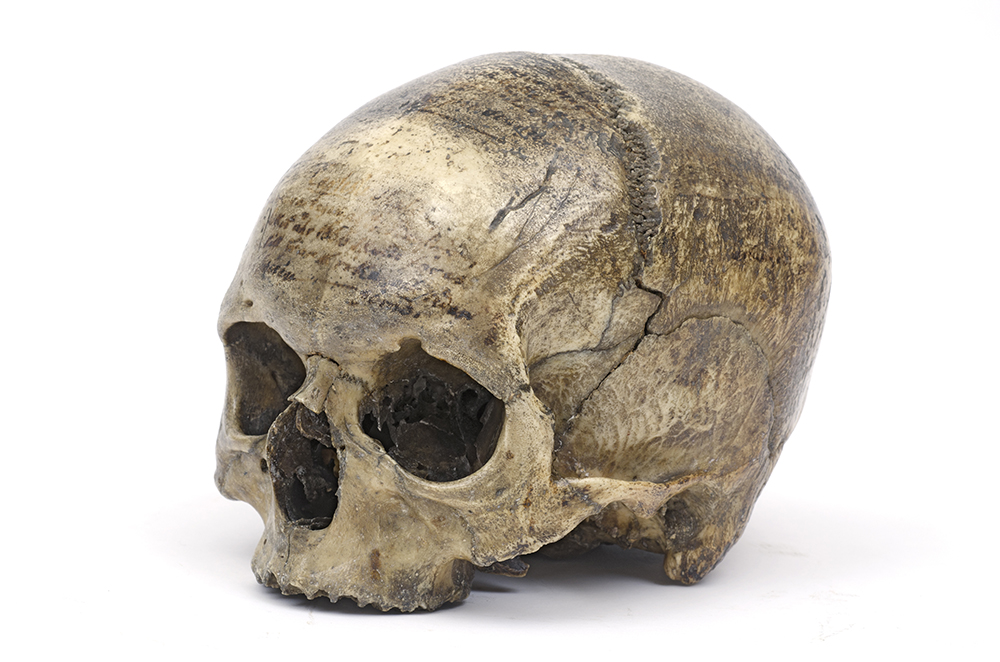

This still leaves the 18,000 human skulls in the basement, a few of which will be returned to their countries of origin, while the rest languish in cardboard boxes awaiting identification and repatriation. In the meantime, one distinguished specimen is already at home. It’s on permanent display among the ‘Who are we?’ exhibits on Level Two.

The skull of René Descartes (©MNHN/JC Domenech)

The skull of René Descartes (©MNHN/JC Domenech)

The skull of the philosopher René Descartes, missing its jawbone and upper set of teeth, rests on a plinth between the cranium of a 30,000-year-old Cro-Magnon Man and a plastic bust of the retired footballer Lilian Thuram, the most capped player in the history of the French national squad. Apparently, this arrangement compromises no one’s dignity. The three exhibits reinforce the important message that we humans are on a journey that has seen us progress from club-wielding troglodytes to philosophers and soccer stars. The sign underneath the philosopher’s skull states that it belongs to ‘René Descartes (1596–1650) Homo sapiens’.

As it happens, the literal translation of Homo sapiens is ‘wise man’, which is a good description of one of the most influential thinkers of the past half millennium. The label on the plinth offers more information.

Descartes was buried in Stockholm, where he had been invited by Queen Christine. During the exhumation of his remains in 1667, with a view to their transfer to the church of Saint-Germain-des-Près – where they would only be re-interred in 1819 – it was noticed that the skull was missing. After many transfers from collector to collector, it was spotted at an auction in 1861 and sent by the chemist Jons Jacob Berzelius to Georges Cuvier. An inscription on the skull shows that it was stolen by the captain of the guards who was in charge of the exhumation.

‘An inscription on the skull …’ Now that so many of us have texts inscribed on our bodies, and even facial tattoos hardly attract a second glance, the fact that the whole of Descartes’ frontal bone is covered in handwriting seems unremarkable. Like old tattoos, the ink has faded with the centuries, though unlike ageing skin, the skull is still taut and firm. The inscriptions were written by former owners of the skull, with the notable exception of Descartes himself. Disappointingly for fans of irony, the philosopher’s most famous dictum – Cogito ergo sum – ‘I think therefore I am’ – is not among the inscriptions. Like tourists with Sharpies at a historical monument, most collectors just wrote their name and added a date, though a more erudite vandal contributed some Latin verse.

Parvula Cartesii fuit haec calvaria magni,

exuvias reliquas gallica busta tegunt;

sed laus ingenii toto diffunditur orbe,

mistaque coelicolis mens pia semper ovat.(This small skull once belonged to the great Cartesius,

The rest of his remains are hidden far away in France;

But all around the circle of the globe his genius is praised,

And his spirit still rejoices in the sphere of heaven.)

There may be many reasons why Descartes’s spirit still rejoices in the sphere of heaven, but having his scribbled-on skull exhibited at the Museum of Mankind is probably not one of them. On the other hand, as a man of science, Descartes would recognise the potential value of the forensic studies that have recently been conducted on the skull. He believed that the soul acted through the pineal gland and would be curious to learn about his post-mortem involvement in the field of mind, brain, and cranial studies. The Museum of Mankind has been associated with this research ever since it acquired the Gall Collection.

¥

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, Dr Franz Joseph Gall, a German-born neuro-anatomist practising in Paris, introduced the world to the science of cranioscopy, subsequently known as phrenology. (Cranioscopy describes the act of observing and measuring the skull, whereas phrenology is the study of the mind/brain, based on cranioscopic observations.) According to Dr Gall, discrete regions of the brain, acting independently of each other, are the location of specific mental and moral faculties such as ‘Agreeableness’, ‘Acquisitiveness’, ‘Firmness’, and ‘Self-esteem’. Gall’s theory was based on a study of the skulls and the death or life masks of three populations: public figures distinguished by their intellectual, social, or artistic achievements; psychiatric patients; and criminals. Gall bequeathed his own skull to the collection, which now belongs to the Museum of Mankind. On the basis of Dr Gall’s dubious contribution to science, a strong case could be made for classifying his skull as a member of at least two of the three populations he studied.

Gall’s analyses of the relationship between talent, madness, criminality, and cranial forms produced a diagram of the brain that resembled a political map of a nation state divided into thirty-seven regions, each representing a trait or faculty. The phrenologist’s task was to determine the relative sizes of these regions in order to identify an individual’s dominant traits. Since Gall believed that a direct correspondence existed between the surface of the skull and the structure of the brain, a detailed measurement of the former would reveal what lay within the latter. Like a surveyor in uncharted territory, a phrenologist would inspect the contours of the subject’s skull, measuring and recording its topographic features. By cross-referencing these to Dr Gall’s map of the interior, one could then calculate the sizes of the various regions, revealing the character of the individual and the race to which they belonged.

¥

Inspired by Gall’s work, the Edinburgh Phrenological Society was founded in 1820, the first of many such bodies in Europe and North America. The value of the Edinburgh Society’s contribution to knowledge is illustrated by a case study published in its journal of 1827. The Society had a special interest in South American crania and was building a museum for its growing collection of skulls and casts. The members were naturally delighted when a new specimen arrived from their South American agent, Mr Malden. In an accompanying note, Malden explained that the skull had been acquired in Chiloa, where it had been lying in the centre of a circle of other specimens. As the members discovered when they consulted the Encyclopaedia Britannica in the Society’s library, Chiloa is a remote island off the coast of southern Chile.

The phrenologists set to work, studiously following Dr Gall’s methods. They measured the dimensions of the skull’s exterior features and then plotted a chart of the corresponding regions of the brain. The findings were revealing. The Chilote’s brain would have exhibited marked deficiencies in ‘Firmness’, combined with a significant over-development in the areas of ‘Veneration’ and ‘Wonder’. It was doubtless as a consequence of this particular combination of faculties that when the Conquistadores first arrived in Chiloa, the Chilotes prostrated themselves in awe of the white gods who had come to rule over them.

The study was a very satisfying confirmation of the power of the phrenological method. The secretary of the Society wrote to Mr Malden to inform him of their findings. Some months later, when the agent’s letter of reply eventually arrived, it contained disturbing news. He pointed out that the members had misread his handwriting, mistaking a ‘c’ for an ‘o’. The skull was not from Chiloa with an ‘o’, in southern Chile, as they had thought. It was from Chilca with a ‘c’ in Peru, three thousand miles to the north. He only dealt in Peruvian skulls, Mr Malden reminded them.

The members anxiously repaired to the Society’s library to consult the relevant entry in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. They were soon reassured by what they read. In the early sixteenth century, a wandering band of just forty Spaniards had stumbled onto the territory of the 70,000-strong Chilca nation. As any competent phrenologist could have predicted, the Chilcans simply surrendered en masse without a fight.

If the Chilcans had turned out to be a warrior race that resisted the Spaniards to the last man, it would have been very awkward, as one contributor to the Society’s journal freely admitted. Happily, this was not the case. Phrenology had proved its worth again. In the end, the writer noted with an air of triumph, ‘Unwarlike submission in Peru differs not from unwarlike submission in Chiloa.’

Malden’s letter also solved a puzzle. Despite the skull’s late owner’s lack of firmness and his excessive tendency to veneration and wonder, the members understood from the start that its form indicated a mind of considerable intellectual acumen. This was inconsistent with what was known of the history of the Chilotes, a race of poor fisherfolk who spent their lives hunkering before the fierce winds that batter their desolate island. Now the truth was revealed. The skull belonged to a member of the noble Chilca branch of the Inca nation. Boasting palaces and temples of unmatched grandeur, the Incan empire once stretched for a thousand miles, a sizeable chunk of which the Chilcans had meekly surrendered to a handful of Conquistadores.

The members recalled with excitement that Mr Malden had found the skull in the centre of a circle of other specimens, leading them to conclude it had belonged to a Chilote headman. In reality, it was now exceedingly probable that the cranium was instead that of a high-ranking Chilcan, perhaps one of the Incan royal Priests of the Sun. Mr Malden believed it might be possible to acquire the skulls of other Incan royals, if the members so wished. They would of course understand the extreme rarity of such objects and the costs involved in locating and acquiring them.

¥

It is easy to dismiss phrenology as nineteenth-century racist bunkum, but the notion that a skull can offer a key to understanding the brain/mind is not entirely without foundation. These days, our models of neurological structure and methods of investigation are more sophisticated. Descartes and the Museum of Mankind have been at the forefront of this research. In collaboration with the Museum, Professor Philippe Charlier, the director of the medical and forensic anthropology unit at the University of Versailles St Quentin, has conducted two studies of Descartes’s skull. In 2014, as part of a broader investigation of disease, death and its rituals, Charlier and his team published a paper in the British medical journal The Lancet entitled: ‘Did René Descartes have a giant ethmoidal sinus osteoma?’ To answer the question, Charlier ran a CT scan on the skull at the Pitié-Salpêtrière teaching hospital. The result: probably yes. The study also concluded that the tumour appears to have played no role in the philosopher’s death from pneumonia.

In 2017, Charlier and his team published another paper, this time in The Journal of the Neurological Sciences. Dr Gall would have been fascinated. The new study attempted the far more difficult task of determining what Descartes’s skull revealed about the philosopher’s brain. What evidence remained of the ‘I’ that thought and therefore was?

In the past, making an endocast – a cast of the cranial cavity – involved pouring liquid plaster into the upturned cavity, waiting for it to dry, and then carefully sawing the skull in two, removing the cast, and (optionally) glueing the two halves back together. Less invasive techniques now exist. Charlier’s team used the teaching hospital’s General Electric High Speed HAS scanner to run another CT scan. Data were exported as a .obj file to a Zbrush 3D package, which produced a digital endocast of the internal surface of the skull, effectively the external structure of the brain. In the discussion of their findings, Charlier and his team report the unsurprising fact that the endocast displays all the classical anatomical features of Homo sapiens and that its dimensions are within the range of variation observed in a sample of extant modern humans. However, compared to the controls, the endocast exhibits a large expansion on the parietal lobes, an area known to be associated with manual dexterity. Team Charlier asked the questions we would all like to have answered: might parietal lobe expansion have had something to do with the fact that Descartes wrote a compendium of music at the age of eighteen, which suggests that he may have played a musical instrument and therefore enjoyed at least a modicum of manual dexterity? Is the fact that Descartes is thought to have performed autopsies further evidence of keen eye and hand co-ordination attributable to those enlarged lobes? Might they also be associated with the philosopher’s better-than-average grasp of maths and visual ideation? Possibly, Charlier et al. conclude, inconclusively.

¥

One of the most interesting parts of the study is team Charlier’s visualisation of the digital endocast. Six rotated views, rendered in chocolate brown, illustrate Descartes’s brain, from top and bottom, left and right, front and back. Displayed in two rows of three divided by neat black borders, the brain views resemble an assortment of Guylian Sea Shells, and could make an interesting souvenir for Museum visitors. To judge by the large discounts on offer, sales of current gift shop merchandise are sluggish. A nineteenth-century ‘phrenological head’ reproduced in Stratford-style cracked porcelain is a case in point. Described on the Museum’s website as an ‘extremely interesting and original gift, a valuable interior décor’, it would have been snapped up by members of the Edinburgh Phrenological Society. But times have changed. The fifteen per cent discount offered to first-time online buyers suggests that demand for porcelain pseudoscience is in decline. The shop also sells a ‘small plate skull’ – a china dish with a frontal view of a skull on it. The skull’s identity is not indicated, but it has a mandible and full set of teeth, so it’s not Descartes’s’. The dish is on sale for €17.50, reduced from €25.

A ceramic beaker is also available. It features a profile view of a skull, possibly the same one that appears on the plate. The beaker too has been reduced, by thirty per cent. If the discounts encourage a final clearance of existing stock, new, more popular lines can be introduced. One candidate is a no-brainer: miniature praline-filled chocolate endocasts of Descartes’s skull. Professor Charlier’s team already has the 3D digital files.

The packaging could include a short introduction to Descartes’s thought, which is the one thing missing from the current display in the Museum. It would be a challenge to condense a series of monumental philosophical works to a statement that fits onto a box of chocolates, but it’s worth trying. Descartes’s ideas are key to understanding many aspects of contemporary Homo sapiens’ condition, including the reason why institutions like the Museum of Mankind came to exist, why some contain enormous collections of skulls they can’t exhibit, and where we all may be headed.

¥

The Philosophy of René Descartes in Ninety-Nine Words

Consider this thought experiment: suppose a Master Illusionist turned the world into a giant illusion. What could you be certain of?

Nothing. You would have to doubt everything. Everything except the fact that you doubt. Thinking proves that you exist.

Correctly applied, your mind’s power to reason can make sense of everything, because it’s all just dull matter. Even your body. Once you understand matter, you can become its master. Robert Oppenheimer knew this. When the father of the atom bomb witnessed the first nuclear explosion in 1945, he said, ‘Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.’

After Descartes introduced the revolutionary distinction between the conscious, living mind and the dead world of matter, Homo sapiens – in the first instance, Homo sapiens europeensis – embraced the seductive idea that the human mind was the measure of all things. The gods that once inhabited earth and air, water and fire were gone, replaced by Reason. Everything could now be measured and managed according to the demands of the thinking mind. If you had a large enough knife and fork, the world and everything in it could be sliced up and served on a plate. Of course, the application of reason to exploit the environment and its peoples did not begin in 1637 when Descartes published Discourses on Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and Seeking the Truth in the Sciences. The silver mines of Peru, for example, and their ore-refining ponds in which thousands of indigenous labourers were forced to wade knee-deep in mercury-laden sludge, had been operating since the Conquistadores first arrived over a century before. All Descartes did was to provide modernity with a manifesto that privileged the power of reason above all else. It would be wholly inaccurate and, well … unreasonable to blame the man for environmental destruction, imperialism, colonialism, industrialisation, urbanisation, commodity fetishism, capitalism, communism, fascism, genocide, atomic weaponry, phrenology, the patriarchy, the climate crisis, or any of the other ills of the past four centuries. It would, however, be fair to say that the distinction Descartes introduced between the thinking mind and the dead matter it could think about has led us to many unanticipated places, some of which have been dark and very dangerous. Just ask the 18,000 skulls in the basement of the Museum of Mankind.

‘The Museum of Mankind’ was shortlisted for the 2022 Calibre Essay Prize. Publication is generously supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.

Endnotes

The Quai Branly runs along the Left Bank of the Seine between the Beir Hakeim and Alma Bridges, close to the Eiffel Tower. Since 2016 the museum has been officially known as the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac.

An ethmoidal sinus osteoma is a slow-growing neoplasm of the paranasal sinuses, occurring mainly in the frontal and ethmoid sinuses. It is benign and relatively common.

Comments powered by CComment