- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An insightful observer

- Article Subtitle: An intellectual portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Alexis de Tocqueville was born in 1805 into an eminent Norman aristocratic family, with ancestors who had participated in the Battle of Hastings and the conquest of England in 1066. This was a family and social milieu that was to be deeply scarred by the French Revolution of 1789–99. His parents were Hervé, Comte de Tocqueville, formerly an officer of the personal guard of Louis XVI, and Louise Madeleine Le Peletier de Rosanbo, a relative of the powerful political figures Vauban and Lamoignon. The couple married in 1793; the following year they barely escaped the guillotine. Louise’s grandfather Malesherbes (Louis XVI’s minister and defence lawyer at his final trial) and both of Louise’s parents were condemned to death, as were her elder sister and her husband.

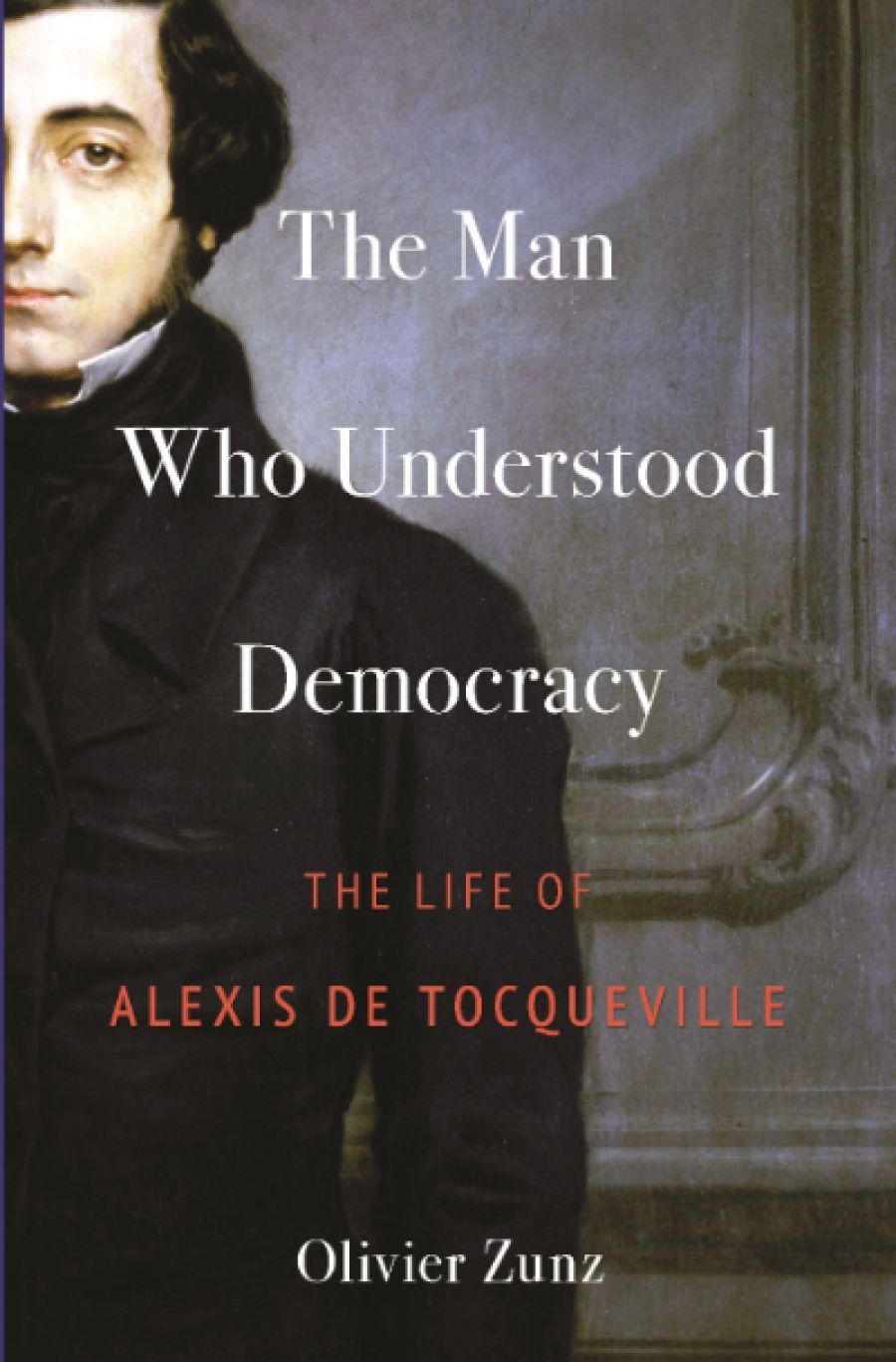

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

%20(1)%20copy.jpg)

- Article Hero Image Caption: Portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville by Théodore Chassériau, 1850, at the Palace of Versailles (Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Portrait of Alexis de Tocqueville by Théodore Chassériau, 1850, at the Palace of Versailles (Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Peter McPhee reviews 'The Man Who Understood Democracy: The life of Alexis de Tocqueville' by Olivier Zunz

- Book 1 Title: The Man Who Understood Democracy

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life of Alexis de Tocqueville

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press, US$35 hb, 472 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/b3o6Wm

Tocqueville’s latest biographer, Olivier Zunz, is the consummate Atlantic liberal intellectual. He was born in France and has a PhD from the Sorbonne, where he met the anti-Marxist historian François Furet during the student revolt of 1968. Furet has remained ‘the surest of guides’ for him. Since 1979, Zunz has been at the University of Virginia and celebrated for his work on the history of US urban society, notably of Detroit, and of US philanthropy, as well as being a leading authority on Tocqueville. His biography of the brilliant French aristocrat is both a homage and a masterpiece. The book is superbly produced and illustrated, as befits Princeton’s reputation and Zunz’s achievement.

The measure of Tocqueville’s intellectual eminence is that he was able to rise above the traumatic history of his own family to reflect incisively on the social and political changes through which he was living. Dismayed by the Revolution of 1830, which overthrew the Restoration monarchy of Louis XVI’s younger brothers, Tocqueville arranged to travel to the United States in 1831–32 with his close friend Gustave de Beaumont. Throughout his travels, his passion for personal freedoms was confronted by his hard-headed realisation that he was observing an evolving new world. At the heart of his quest was, as he wrote to his celebrated uncle Chateaubriand in 1835, ‘a feeling carved deeply into my heart: the love of liberty [and] an idea that obsesses my mind: the irresistible march of democracy’.

The trip, ostensibly to study penitentiary systems, was also to result in one of the classics of early sociology, Democracy in America (2 vols, 1835, 1840). In the conclusion, Tocqueville reflected on the fundamental changes he was observing across the Western hemisphere, but worried about where these might lead: ‘The nations of our time cannot prevent the conditions of men from becoming equal, but it depends upon themselves whether the principle of equality is to lead them to servitude or freedom, to knowledge or barbarism, to prosperity or wretchedness.’

By ‘equality’, Tocqueville meant democracy, or at least white manhood suffrage. The central conundrum for him was how to avoid democracy becoming ‘the tyranny of the majority’, or worse: his family’s trauma was embedded in his anxiety. His optimism for the United States was based on his admiration for Americans’ enterprise, community spirit, and scepticism about the role of government, despite the drab conformism of public opinion.

Tocqueville’s command of English was improved by his nine months in North America. His views were also formed by subsequent travels and acute observation of poverty in England and Ireland. After a series of desultory relationships, in 1835 Tocqueville married an older and middle-class Englishwoman from Portsmouth, Mary Mottley, with whom he evidently had a companionate and happy, if childless, life. Zunz’s biography, however, is very much an intellectual portrait: the individuals of Tocqueville’s milieu are all there in careful detail, but this erudite volume explores the complexities, hesitations, and passions of Tocqueville’s mind rather than his personal emotions and relations. He seems to have been a shy and reserved man, more at home with writing earnest letters than exchanging pleasantries.

Tocqueville was intransigent about abolishing slavery – which he saw as ‘violating the most sacred rights of humanity’ – and was proud that France had done so during its revolution. But the lifelong struggle between his heart and head was to be evident in his emotional responses to suffering – his disgust at the treatment of Native Americans, Algerians, and the poor in England and Ireland – but also in his hard-headed acceptance of such cruel hierarchies as embedded in all societies. Despite castigating the horrors of President Andrew Jackson’s forced deportation of the Chocktaw Nation from Alabama and Mississippi in 1831, the ‘Trail of Tears’, Tocqueville concluded that the ‘Indian race’ was both inferior and ‘doomed’. Indeed, he came to see the colonisation of Algeria and a forced separation of colonists and Algerians as the French equivalent of the US frontier, promising the flourishing of the ‘small-scale capitalists’ he so admired.

At times, the understandable esteem in which Zunz holds Tocqueville leads him to soften his superb portrait of a brilliantly insightful observer who also accepted social and racial cruelties as the price of social order. Nowhere was this more apparent than in Tocqueville’s admiration for General Léon Lamoricière, notorious for his uncompromising, even exultant, killing of resistant Algerians after 1830 and of insurgent Parisian workers in June 1848. Democracy may have been one manifestation of the modern world that Tocqueville accepted as inevitable and manageable, but ‘socialism’ was not. The insurrection of impoverished Parisians in 1848, calling for a ‘social republic’ and unemployment relief, was described by him as a battle over ‘property, family, and civilisation – in short, everything that makes life worth living’.

Under the July Monarchy (1830–48) and Second Republic (1848–51), Tocqueville personally sought to embed the practices of constitutional government and electoral politics in French political life. He was a parliamentary deputy and minister before abandoning public life after Bonaparte’s nephew Louis Napoléon seized power with the army in December 1851. He then devoted himself to writing The Old Régime and the Revolution, one of the great classics of historiography, a work unfinished at his early death from tuberculosis in 1859.

Tocqueville’s main argument about the French Revolution was the continuous power of central authority, from the centralising state of Louis XIV (1638–1715) to Napoleon Bonaparte, who seized power with the army in 1799. The most radical change through the Revolution, according to Tocqueville, was the destruction of the institutions of feudalism, both the traditional institutions dominated by the nobility and the vestiges of the feudal or seigneurial system in the countryside. The Revolution sought to replace the ancient feudal structures with new institutions based on popular sovereignty, civic equality, and liberty. Unlike the United States, however, where a society developed based on private property, pragmatic religious pluralism, and individual freedoms, he argued that in France people still relied too much on central authority.

Zunz shares Tocqueville’s judgement that greater social equality is inherently threatening for liberty and that the strength of the United States’ ‘democratic experiment’ stems from economic freedoms. There are many who would contest such a premise. Certainly, however, Tocqueville’s untimely death spared him from witnessing the socialist Paris Commune of 1871, which would have reinforced his worry that democracy and liberty could not coexist, and the American Civil War, where his satisfaction at the survival of the Republic and the abolition of slavery would have been tempered by his dismay at the carnage of racial hatred and civil discord.

Comments powered by CComment