- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Poetic choreography

- Article Subtitle: A further Selected Poems from Robert Gray

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

According to his author’s note, Rain Towards Morning is ‘a definitive book’ of the poems Robert Gray wishes to preserve. Nameless Earth (Carcanet, 2006) is the most generously represented of Gray’s previous eight books. This is followed by his mid-career volume Piano (1988) in which he first began to publish a range of poetry with tight rhyme schemes and controlled rhythms. More than a third of the poems Gray has chosen for Rain Towards Morning are these formal or semi-formal compositions, indicating that he wishes to showcase this aspect of his work. Fewer poems have been chosen from his free verse books Grass Script (1978), The Skylight (1983) and Afterimages (2002), arguably his best books.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

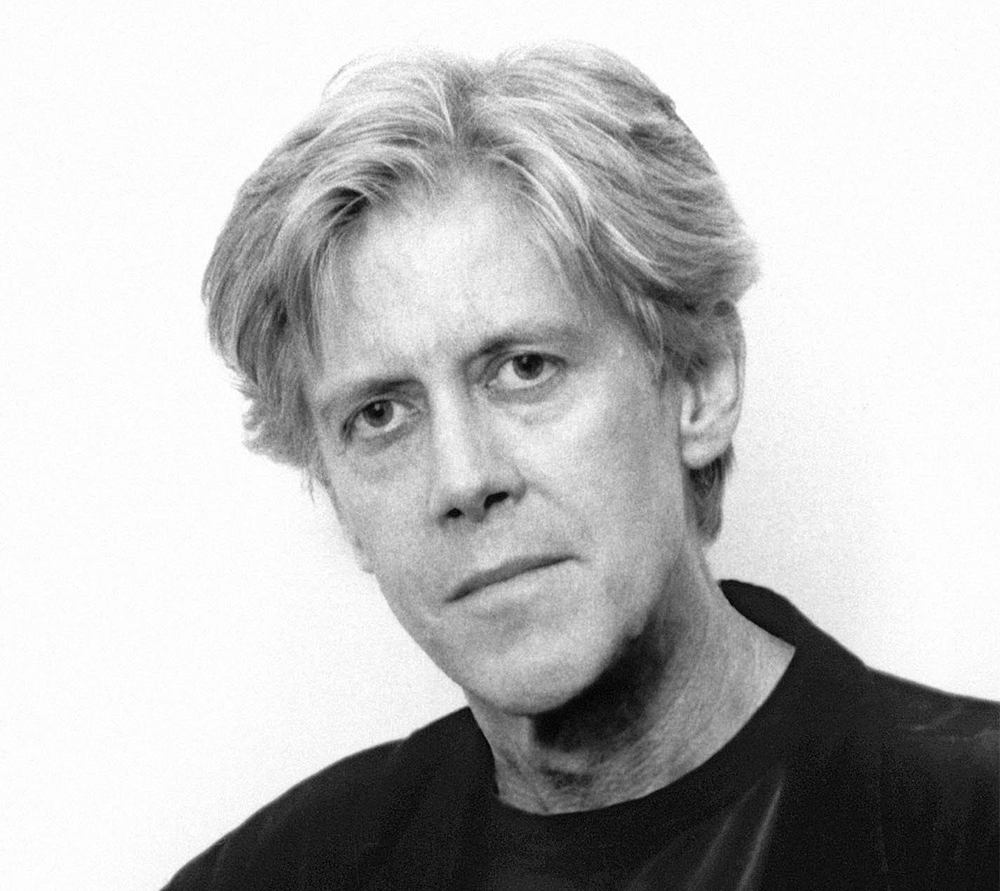

- Article Hero Image Caption: Robert Gray (photograph via Giramondo)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Robert Gray (photograph via Giramondo)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Judith Beveridge reviews 'Rain Towards Morning: Selected poems and drawings' by Robert Gray

- Book 1 Title: Rain Towards Morning

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected poems and drawings

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $29.95 pb, 238 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/NKq5nP

Readers will find a great many of Gray’s most admired works included in this new selected: ‘The Meatworks’, ‘For the Master, Dōgen Zenji’, ‘Late Ferry’, ‘Flames and Dangling Wire’, ‘Dharma Vehicle (but only part 1), ‘The Dusk’, ‘Diptych’ , ‘Memories of the Coast’, ‘Curriculum Vitae’, ‘Harbour Dusk’, ‘Life of a Chinese Poet’, ‘After Heraclitus’, ‘In Departing Light’, ‘The Drift of Things’, ‘The Fishermen’, ‘Flying Foxes’, ‘Wing Beat’ – poems which have established Gray as one of the finest free verse poets in English over the past fifty years. However, I regret the omission of such poems as ‘A Sea Shell’, ‘Pumpkins’, ‘The best place …’, ‘Bondi’, ‘Mr Nelson’, and especially the magnificent ten-and-a-half-page, free verse poem ‘Under the Summer Leaves’ (surely the best poem in Piano), which he dramatically reduced to thirty-four lines in Cumulus: Collected poems (2012). These would be much better inclusions than some of the rhymed poems, as only a few of these, I believe, are successful.

Part of the problem with Gray’s adoption of formal procedures is that the ear competes with the eye. Hardly anyone can match Gray’s resplendent imagistic acuity, his ability to draw out details and scenes with immense depth and perspective, his persuasive and startling comparisons, his moral and philosophical enquiry, his use of both loose and taut lines to pull a reader through his cadences and movements of thought. Unfortunately, his formal templates draw too much attention to themselves and put his natural voice under pressure with rhymes that are often weighty and overdone. The poem ‘Black Landscape’, after a description of cicadas, ends with: ‘if you tilt your hand, you can make / a light, pale blue and frail / as after sunset. I told a girl once, in Ireland, of cicadas; / she said, ‘We only ever had a snail.’ Or this from ‘The Circus’: ‘I look back and there is an elephant / being hosed, that’s lambent’.

Too often the rhymed poems haven’t come to terms with constraints of the rhymes or heaviness of syntax. The syntax in Gray’s free verse poems is more effortlessly yoked to his observations and thoughts. Compare these lines from the heavily rhymed, ‘Description of a Walk’ to the rhythmic flow of lines from ‘The Creek’:

Uphill, warped arcades of bush, rack on rack;

reiterative as cuneiforms. Bacon redness of bark,

or smooth wet trunk of caterpillar green,

and some with a close dog’s fur, greyish black.Grey weather between the high-grown, thickly gathered trees,

the lean

sparse-leaved eucalyptus poles,

parsley-

shelved, but with frail

grey-green leaves, and down the slope the kettle-black

lower boles

among which the water’s glimpsed – the secret creek in khaki

that beats

like a vein at the throat

of someone

who’s lying hidden.

The first example loses energy because of the easy rhymes and lack of enjambment. Gray’s visual fluencies need the freedom that free verse offers, not the restrictions of rhyme. The rhythms in ‘The Creek’ are so much more poised, even restful as compared to the constricted flow in the former poem.

Rhyme in the right hands can be glorious, but often in Gray’s poems the rhymes struggle. One wonders what might have become of poems such as ‘The Shark’, ‘Description of a Walk’, ‘To John Olsen’, ‘The Circus’, and ‘Ekphrasis’ had they been written in free verse. The formal poems which are more successful – ‘Harbour Dark’, ‘In one ear …’, ‘Wing Beat’, ‘Thomas Hardy’, and ‘The School of Venice’ – work because they employ clearer rhythmical structures. ‘The School of Venice’ succeeds because the lines are of varying lengths, the enjambment makes the syntax more fluid, and consequently the lyrical intensity is less forced and carried by the flow of thought.

Gray is not an innately lyrical poet; his strengths lie in narrative, description, juxtaposition, exposition, and in noting and appreciating phenomena. His imagery achieves an exactness and inventiveness which brings both mind and matter into powerful cogency. He will often evoke sensual panoramas to explore abstract questions, mostly involving principles of morality and the nature of reality, or create tableaux of rumination and mood, the subtle nuances of which can be most compelling. Many poems are transactions between human sentience and insensate landscapes, most memorably the mid-north coast of New South Wales. His work glories in what can be seen and apprehended by the senses, and while his earlier poetry resonated with Buddhist ideas, his later work is more linked to Western philosophers and is more expository.

Certainly, this volume shows the breadth of Gray’s poetic enterprise throughout his career, and I imagine this has been a strong impetus behind the choices. He has not been one to rest on his haunches and repeat the same compositional procedures, even if his foray into formal poetry has not been entirely successful. He has tried to replenish his approaches and extend his range of skills by employing both short- and long-form free verse, haiku-

like vignettes, prose poems, syllabics, formal and semi-formal constructions. However, it appears that Gray has an unsettled relationship to his work, given that he has published a number of ‘Selecteds’ over the years (more than any other Australian poet), which often contain (sometimes substantial) revisions of poems. Some of the poems in this latest volume have had changes, albeit only minor ones, made to them since their appearance in Cumulus, which Gray also described as the decisive versions.

This said, Rain Towards Morning is a book of immense pleasures. The best poems are wonderfully evocative and impressive for their supple and kinetic free verse style, their incomparable imagistic choreographing set alongside profound philosophical exploration.

Comments powered by CComment