- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Australia’s fraught relations with China

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A long way to go

- Article Subtitle: Australia’s fraught relations with China

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

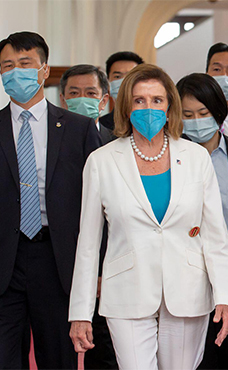

Australia’s fraught journey with China continues. The Albanese government now wrestles with the same harsh global and regional realities as its predecessors. The crisis brought about by US House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in early August now appears to have ruptured much of the initial attempts on both the Australian and Chinese sides to at least begin talking to each other again.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Nancy Pelosi and President Tsai Ing-Wen at the presidential palace in Taipei (Image credit © Taiwan Presidential Palace via ZUMA Press Wire/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 'A long way to go: Australia’s fraught relations with China' by James Curran

On being elected in May, Anthony Albanese and his ministers moved quickly to strike a new tone for Australian diplomacy. They declared ASEAN centrality the lodestar of their regional approach and moved to assuage anxieties in the Pacific over China’s strategic reach and climate change. While the fledgling government has broken with the Morrison government’s tendency to shout at China, it does not wish to be wedged by its political opponents on national security matters so early in its term.

This means that Canberra and Beijing are once more talking past each other. The crisis over Taiwan has only sharpened the rhetorical swords. When Foreign Minister Penny Wong joined with her American and Japanese counterparts to condemn China’s display of brute force over the Taiwan Strait – in what amounted to a virtual blockade of the island – the Chinese embassy in Canberra resorted to its ‘wolf warrior’ diplomacy, demanding that Australia treat its handling of the ‘Taiwan question with caution’, and reminding Canberra of Japanese aggression towards Australia during World War II.

Before this crisis erupted, Albanese said there is still a ‘long way to go’ with China and that the relationship will remain ‘problematic’. In the wake of Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan and its emboldening effect on belligerents in both Beijing and Washington, those words now seem quaint. Australia is now intimately linked to possible war in the Taiwan Strait by bipartisan policy.

Thus Wong’s earlier talk of ‘stabilising’ the Australia-China relationship may well prove to be a forlorn hope. In her early weeks in the job, Wong engaged in an awesome schedule of shuttle diplomacy across Southeast Asia and the Pacific to promote a renovated image of Australia to the wider world. But the prevailing climate of a ‘new Cold War’ with its decreed fault-line of autocracies versus democracies has the stronger hold. Indeed, on a visit to Madrid for the NATO summit in July, Albanese appeared to give at least rhetorical support to the idea that the world was now a ‘single theatre’ of operations, with the ‘West’ facing Russia in Europe and China in Asia. He hoped that Beijing would learn the lessons of Russian aggression. He seems to buy the line that the West must defeat Vladimir Putin in Ukraine so that it stands as a warning to Xi Jinping.

Then Defence Minister Richard Marles, having preached the virtues of ‘reassuring statecraft’ in a major speech at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June, showed his true colours during a visit the following month to Washington for talks with US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin. While there, Marles delivered a major speech on the relationship between Australia and the United States. He spoke of the alliance in terms much like his predecessors did in London at the height of the British Empire. The relationship was not only bound by the ANZUS treaty, he said: it was a ‘network of people’ committed to a ‘shared project’.

But he went further. Marles ushered in a new concept for the alliance. Australian and US military forces would henceforth be not only interoperable but ‘interchangeable’. Spelling it out, he said the two forces could then ‘operate seamlessly together, at speed’. Marles is still sending former defence minister and now opposition leader Peter Dutton’s message (albeit a little differently) that Australia is readying for war.

All of this shows just how much Australian relations with China continue to represent something of an odyssey. As former Prime Minister Gough Whitlam instructed Stephen FitzGerald, the first Australian Ambassador to China in 1973: the new envoy would have to ‘steer a course between the Scylla of unnecessary suspicion … and the Charybdis of apparent carelessness’. Whitlam was stretching out the tightrope that subsequent governments would have to traverse.

While many commentators in Australia hoped for an immediate reset with Beijing with the coming of the new Labor government, such expectations were both undefined and unrealistic: the ‘China threat’ narrative and rhetoric still pulse strongly through the security and intelligence apparatus so dominant in Australia’s global outlook. The key advisers who shaped the policy response to China under Scott Morrison have been left in place. That means the harder thinking about the connection between economic and national security is not being done at the highest levels.

Negative attitudes towards China in the political culture and populace are now entrenched. Over the preceding four years, the chief proponents of the view that Australia faces an existential threat to its security and prosperity – particularly those in the press, security services, intelligence agencies, and government – marshalled an array of slogans that touched on powerful memories in the national psychology. They put historical experience into a straitjacket and indiscriminately applied the supposed lessons of ‘Munich’, ‘appeasement’, and the Cold War.

The Australia–China relationship has enjoyed three sustained periods of political and diplomatic sunshine: from the 1970s to the late 1980s, from late 1996 to 2007, and then again from the end of 2009 to 2017. These high points of the relationship occurred not only because of astute management by successive governments in Canberra, which recognised that China’s opening was a positive for the national and global economy, but because China was broadly set on a path to gaining global acceptance as a major economic and political power.

During these periods, too, Washington was either distracted by the Soviet Union and then the hubris of its unipolar moment at Cold War’s end or focused on the Middle East in the War on Terror. Even so, at nearly every point, even in the late 1950s, the Americans dropped enough hints – privately and publicly – that revealed nervousness about the warmth of Australia’s China embrace. From the election of John Howard in 1996, successive Australian governments made sure that the US alliance was reinvigorated – structurally, institutionally, and emotionally.

The US alliance has become a path to safety and reassurance for both sides of Australian politics. A bedrock reality in Australia’s strategic past and present is that it has no real alternative to the US security relationship. But since at least the late 1990s, the task of defining the parameters of self-reliance has been discarded.

Doing more for the United States, irrespective of whether the Americans will ever concede they are satisfied, has become a default policy setting for both major political parties in Australia. The result is that Australia is little more than an auxiliary in whatever strategic decisions the United States makes. For many in the national security community in Canberra, the US alliance has become a way of life. As Marles’s visit to the American capital shows, there is now an official and formal Australian policy of ‘alliance maintenance’.

This is a strategic gamble, possibly the greatest in the history of Australia’s relations with the world. Its politicians bank on a hope that the internal strife in the United States is but a passing phase, that once again America, as it has in the past, will recover its purpose following a period of drift and chaotic introspection. Yet the socio-cultural conflict that predated the coming of Donald Trump, and which he exploited while in power, has thrown doubt on America’s resolve to once more assume the role of world leader. The United States will not turn away from the China challenge – that would be against its very nature, and its primacy is at stake. But it may well find that the gap between its resolve and its capability has widened.

If the past four to five years have been challenging, the next few will very likely be harder. In all likelihood, Australia will be dealing with a president who has lost control of Congress. The discipline of the Biden administration in resisting the policies and intellectual environment of a new Cold War will likely be eroded. Then, within the next term of the Australian electoral cycle, the prime minister will need to deal with a United States conceivably led from the White House by Trump himself or a Trumpian figure in his image. It is possible that this would follow a tightly contested presidential election, with the potential for yet more domestic disarray in the United States. The Trumpian obsession is a managed trade with China, where the United States can deal with China, to the exclusion of its allies. This would not only bring further economic costs to Australia; it would also have the potential to inflame the European Union and damage US alliances with Japan and Korea.

The inescapable reality, however, is that Labor – as much as its political predecessor – has banked on American resolve in resisting China. More than at any point since World War II, Canberra is tucked into the blanketing embrace of US Asia policy, a policy that is still in formation. The Albanese government endorses that stance even as it continues to craft a new language to set out Australia’s role and place in the world.

Comments powered by CComment