Following the recent federal election, we invited several senior contributors and commentators to nominate one key policy, direction, or reform they hope the Albanese government will pursue.

Joy Damousi

The one single policy decision that would send a powerful message to Australia’s research community would be to abolish the law that currently permits a government minister to veto Australian Research Council grants.

The independence of research in any field is core to a thriving, healthy, and robust democracy. It is a fundamental principle of best practice in research that scholars are allowed to work rigorously and fearlessly – free of any threat of government intervention that might shape or determine it. And yet, under the Australian Research Council Act 2001, the minister of the day has the power to overturn the decision made by a panel of experts to fund research projects. This ministerial intervention is unprecedented in countries that fund research activity and that value the vital importance of independent thought, the pursuit of new knowledge, and vigorous critique: principles that underpin the most outstanding and distinguished research projects.

The Haldane Principle has been invoked in these discussions. The Haldane Principle states that funding decisions on research grants should be made by independent research councils, free of any intervention by politicians. Since 1918, when it was enshrined in British government policy, it has been one of the guiding principles of research in the United States and in countries across Europe.

After the most recent intervention by acting education minister Stuart Robert on 24 December 2021, when six projects were vetoed on the grounds that they did not represent value for money and were not in the national interest, the research community across Australia covering all fields in STEM and HASS called for the abolition of this law. Professional bodies, the learned academies, and individual researchers were vociferous in their denunciation of Robert’s use of the veto. An open letter expressing indignation and concern about the veto was signed in January 2021 by over 140 members of the ARC College of Experts; two resigned as an act of protest. A parliamentary inquiry was held where there was overwhelming opposition expressed against the continued use of the veto. Although only one side of politics has exercised the veto, both support its existence. When the Greens education spokesperson Senator Mehreen Faruqi tried to amend the Act to repeal the veto, her Bill was defeated when both Liberal and Labor parties voted against it.

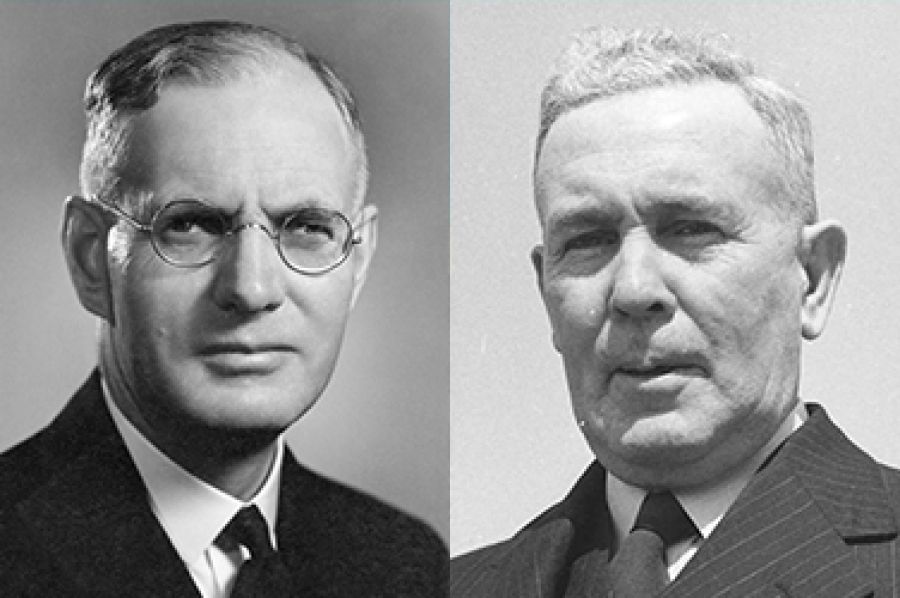

Since the establishment of the ARC in 2001, a minister has exercised a veto over grants on four occasions. The ministers, all from the Liberal–National Coalition – Brendan Nelson, Simon Birmingham, and Stuart Robert (with Dan Tehan upholding Birmingham’s decision) – intervened to stop grants that the ARC peer review process involving expert assessors in the field had recommended to the minister for funding. It is incumbent on the new Labor government to show leadership for the future in ensuring independence for researchers by abolishing this draconian legislation. The argument put forward by successive governments is that the veto is necessary because it ensures ministerial oversight and accountability of the use of public funds.

There are three further aspects of this argument that require interrogation:

First, the grants in question are all in the humanities disciplines. This suggests an insidious bias against humanities research conducted in areas and on topics conservative politicians believe are not worthy of study, and/or the individual minister believes should not have access to funds. These include topics such as various aspects of climate change; studies of sexuality; Cold War politics; work on China; and gender studies. All the projects affected were examined and assessed by an expert panel and subject to the most rigorous examination by peer review. The political implications are clear when on a minister’s whim a research grant is dismissed, raising concerns about censorship, academic freedom, and the integrity of the review process.

Second, and relatedly, a ministerial veto does not apply to grants awarded by the National Health and Medical Research Council. It is to be applauded that medical research is not subject to a veto. But this inconsistent position is inexcusable; it is difficult not to conclude that humanities research in the ARC scheme is intentionally targeted.

Third, accountability of public money is imperative in the use and dispensing of ARC funds. There is no argument with this principle, and it is one that all researchers must uphold. Public accountability, however, cannot be used as an excuse for an individual minister to allow their personal judgement to cloud what research is appropriate for funding and what is not. Other measures currently exist through the Excellence in Research exercise, which demonstrates the quality and quantity of research being produced through funded projects.

As the nation moves to a more positive and optimistic political landscape after nine years of conservative rule, the research sector looks to the Labor government to abolish this invidious law.

Joy Damousi is Director of the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences at Australian Catholic University. She was President of the Australian Academy of the Humanities from 2017 to 2020.

Stephen Charles and Catherine Williams

If the Labor Party’s resounding win at the election was a considerable surprise, so was the number of independents who took seats formerly considered safe by Liberals. The teals, as most of these independents are known, proclaimed support for climate action and a strong National Integrity Commission (NIC). In doing so, they shared the views of a large proportion of those elected, since Labor and the Greens, along with most of the former crossbench, certainly support such action. Only the former Coalition members were laggards. Since the election, the new Coalition leaders, Peter Dutton and David Littleproud, have both asserted support for a robust integrity commission. The new parliament is expected within a year to establish a much stronger NIC than Christian Porter proposed in 2018, as well as a series of crucial reforms to accompany it.

Robert Gottliebsen in The Australian (May 25) wrote that the Integrity Commission will be ‘a game-changer’, noting that it will ‘dramatically improve the way both the Australian public service and Canberra politicians operate’, which is precisely what those arguing for an NIC hope to see. There remain, however, difficult questions for the new parliament to settle.

First, it will be necessary to decide the jurisdiction of the NIC, including the ambit of the term ‘corrupt conduct’. The definition will be broader than just the criminal offences that the Porter model insisted on for politicians and most public servants. That model would have seriously limited the NIC’s jurisdiction, as well as providing a threshold which created obstacles to impede the investigation of programs such as the Community Sports Infrastructure Program (known later as the Sports Rorts scandal). Much governmental impropriety does not, at least at the outset of an investigation, include criminal offences.

Secondly, the NIC’s ability to hold public hearings must be considered. No one suggests that all the NIC’s investigations should take place in public, rather that only after detailed, often prolonged, secret hearings and other examination of material will a conclusion be reached as to whether it is in the public interest to conduct a public hearing. In this way, the subject’s reputation will be protected.

Next, it will be necessary to insist on the fairness of any investigation, which can be provided for in various ways: by virtue of the oversight of the Federal Court, or by a provision which requires natural justice to be given to a witness or suspect, or by explicitly requiring certain steps to be taken by the NIC.

The NIC must then be able to make public findings of fact, including of corrupt conduct. It may be expected that the emphasis of the NIC will, as was suggested in The Australian, be on integrity rather than on corruption. Examples of what Transparency International regard as corruption include matters such as the Sports Rorts and the Car Park Rorts. Most politicians and public servants are not corrupt, but an NIC will in future foster the expectation that they must act with integrity. This means that before deciding to award a contract or other position, those involved must have made a careful study of all relevant factors and must have given proper opportunity for competitive tenders to be received and fairly considered. Frank and fearless advice on these issues must be given by senior public servants to politicians and acted upon by them.

Oversight will be a critical matter, including by an inspector, by a bipartisan parliamentary committee, and by the Federal Court, and it will be necessary to consider whether there should be a means of appeal, or rectification, if a reputation has been damaged by a finding which is wrong or unfair.

These are only some of the issues that parliament must consider in the establishment of the NIC, and there are many other matters that require consideration and action. Codes of conduct for public servants, parliamentarians, and ministers must be in place and made effective by enactment. Ministers’ diaries must be made public. Lobbying must be properly regulated. Political donations pose a direct threat to the integrity of Australian democracy and should be capped, as should expenditure by parties and candidates before an election. The issue of a revolving door should be resolved by, say, legally prohibiting politicians and public servants from accepting private sector positions in areas in which they had previously worked officially.

The Labor Party, before the election, positioned itself as intent on renewal and integrity, determined to rid Australia of rorts and programs that misuse vast amounts of taxpayers’ funds for improper electoral purposes; and also to tackle other misconduct such as favour for favour, returning benefits and access to large donors, and giving contracts to friends and allies.

Now is this government’s chance to demonstrate real integrity. We look forward to the result. Our democracy, judged in 2022 world rankings (Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index) to be among the fastest decaying from integrity into corruption, must be defended and rebuilt, whatever the cost.

Stephen Charles and Catherine Williams co-authored Keeping Them Honest: The case for a genuine national integrity commission and other vital democratic reforms (Scribe, 2022).

Frank Bongiorno

It took me until 19 May to see that a change of government might offer something better than relief from the nightmare of the Abbott–Turnbull–Morrison era. At a Labor doorstop in Sydney, a journalist questioned the value of offering a childcare subsidy to people earning more than half a million dollars a year. As usual, in responding, Anthony Albanese took a while to get there, lurching this way and that like a plane negotiating turbulence on its course towards the runway. But once he landed, it began to seem that he might lead a government with a Labor soul.

At first, he started talking windily about ‘class warfare’, the implication being that no one could accuse him of that, given that benefits were being offered to the wealthy. That made him sound like a Hawke-era Labor leader. No thanks.

Then he started talking the language of feminism: a woman wanting to work full-time should not suffer on the basis of her husband’s income. That was better, signalling Labor’s support for women’s rights and opportunities. Good, but no surprise.

But then Albanese started to talk a language that has been less familiar among Labor leaders since Gough Whitlam’s day. He started to talk in the language of universalism. Once the effects of Labor’s childcare policy had been reviewed, he said, the government would consider moving to ‘a universal subsidy’.

Then a personal story. Albanese likes these – especially involving his mum. When Kerry Packer had a heart attack, Albanese recalled, he went to Royal Prince Alfred Hospital Emergency Department, the same place that looked after Albanese after a car accident, and the same place his mother attended as an invalid pensioner – sadly, she never made it home. ‘I literally was in the same room,’ he added. ‘Public services which are universal make a difference to strengthen our society. They do. Our medical system is a public universal service. And I have said quite clearly that childcare is something that we should consider as a service that benefits the entire society.’

Talk is cheap, but this is quite different from the language of targeted welfare that increasingly became the norm in the Hawke era, building on an older Australian tradition of means-tested social security funded out of consolidated revenue. There was always another strand to Labor thinking: a universalist one. It was in play in 1912, when the Fisher Government introduced a maternity allowance of £5 on the birth of a child, in or out of wedlock, alive or stillborn. It was, like the Albanese policy on childcare, feminist – the payment went to the mother, as an assistance to her – and it was universal for white women (in line with the racism of the times, it excluded Indigenous women). The Whitlam era saw a boost to ideas of universal provision and the Hawke era a retreat; although Medicare, which revived the Whitlam government’s short-lived but popular Medibank, embodied the principle.

Labor is not offering free and universal childcare. But its subsidies for low- and middle-income earners are substantial, with significant increases on the current rates for the first child in the family in care. For families earning $75,000 or less, the subsidy is set at ninety per cent. That rate declines as incomes rise but remains generous well up the ladder – a family on $200,000 would still get back almost two-thirds of the cost. The policy is progressive and redistributive, while being designed to lift workplace participation and productivity. It will, of course, encounter the challenges that all governments now face, in terms of both cost and quality, when pursuing policy goals through marketised social services. And the fiscal and economic environment will pose many difficulties. In particular, Labor is constrained by the revenue hit that will come from the third stage of the massive income tax breaks recklessly initiated by the Morrison government, and which a humiliated Labor opposition agreed to soon after its 2019 defeat. These sit alongside the many other tax benefits that this country offers its wealthiest, from superannuation concessions through negative gearing on investment properties, to franking credits on shares to people who pay no tax.

Albanese is a child of the Whitlam era. While he was raised in straitened circumstances, he benefited from public provision: in housing, pensions, and education. Tom Uren, doyen of the New South Wales left and Minister for Urban and Regional Development in the Whitlam government, was his mentor, a ‘father figure’ to him, and, for a time, Albanese’s employer. His dilemma will be that of pursuing a path towards the universal provision of services that he sees as being for the public good in a constrained economic environment – and with a structurally hostile media – mainly quiescent during years of Coalition profligacy, allowing Labor little leeway, however cautiously it proceeds.

Frank Bongiorno is Professor of History at the Australian National University.

Dennis Altman

Not since John Curtin came to power during World War II has a newly elected prime minister or his foreign minister been so swiftly immersed in international affairs. When Anthony Albanese flew to Tokyo on his first day in office, President Joe Biden remarked that he would be excused were he to fall asleep during the meetings. No sooner back in Canberra, Penny Wong flew off to Fiji, clearly a response to China’s courting of the region. While there were good reasons for this frenetic activity, it hardly replaces the need for a deep repositioning of Australia’s place in the world.

The incoming government shares two central assertions with its predecessors: faith in the US alliance and distrust of China’s ambitions. It has one striking difference, and that is a willingness to make climate change central to its domestic and foreign policies. This alone should ensure that Wong can establish a better rapport with Pacific Island states than could the Morrison government.

The underlying assumption of Australian foreign policy remains supporting American efforts to limit the influence of China, with the hope of retaining the ‘rules based international order’. Undoubtedly, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made this a popular position, although there is a certain hypocrisy in denunciation of China’s ties with Russia while passing over those of India.

Reappraising Australia’s role in the world might begin by questioning the centrality of the US alliance. It would mean greater attention to the attitudes of the countries of Southeast Asia and less willingness to echo the rhetoric of Washington and London.

To proceed on the assumption that growing hostility with China in inevitable is likely to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. While China is an autocratic and brutal dictatorship, it is also behaving as do all great powers in seeking dominance within its region. Liberal democracy at home restrained neither Britain nor the United States from pursuing imperial ambitions abroad.

In her pre-election speeches, Wong reasserted the importance of relations with Southeast Asia, a welcome shift from the bizarre Anglospheric preoccupations of the Morrison government. The countries of ASEAN range from corrupt autocracies to populist democracies, but they all seek to balance the clout of China with the need for national autonomy. Closer relations with Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, etc. might require Australia to speak less of its partnership with Western democracies and more about genuine global inequities.

Warm rhetoric about shared democratic values cannot disguise the reality that many countries in our region have appalling records in human rights. Nor will language about our ‘Pacific family’ prevent small Pacific countries from balancing their reliance on Western powers by creating ties with China, however distasteful we find them. The realities of geography and trade mean that Australia, too, needs to find ways of coexisting with China, even if this distances us from the United States.

Labor has supported the AUKUS arrangement, which presumably means that nuclear submarines will arrive in Australia sometime after the next election but four. Sadly, it seems that Labor is as willing as the Coalition to assume that Robert Menzies’ appeal to our great and powerful friends in the Atlantic north remains an eternal guarantee of Australian security.

Albanese is likely to establish a close relationship with President Biden, as did John Howard with George W. Bush and Julia Gillard with Barack Obama. After a rocky start, both Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison did well to maintain relations with the Trump administration, although in ways that may have reinforced regional perceptions that Australia was too subservient. But if Trump is re-elected in 2024, there may be real costs to that closeness.

It is impossible to predict whether a future United States will move towards greater belligerence or greater isolationism, but a prudent Australian government should prepare for both possibilities. Our security would be greatly enhanced if we balanced growing military expenditure by investing more heavily in diplomacy and international development. The more we identify with ‘the West’ and the more deeply we incorporate ourselves within US military planning, the more difficult it will be to manage a radically different international environment.

During the campaign, Albanese was careful to distance himself from Paul Keating, whose disdain for current foreign policy orthodoxies was seen as electoral suicide. Now in office, Labor might well reflect on Keating’s warning that the previous government displayed ‘a monster level of incompetence to forfeit military control of one’s own state’ (The Age, 22 September 2021).

Dennis Altman is a Professorial Fellow in the Institute for Human Security at La Trobe University.

David Latham

Having a government that supports the role the arts play in our cultural and social life is a welcome change, but the uncertain economic situation for artists is one that needs to be addressed by Labor in funding and in policy.

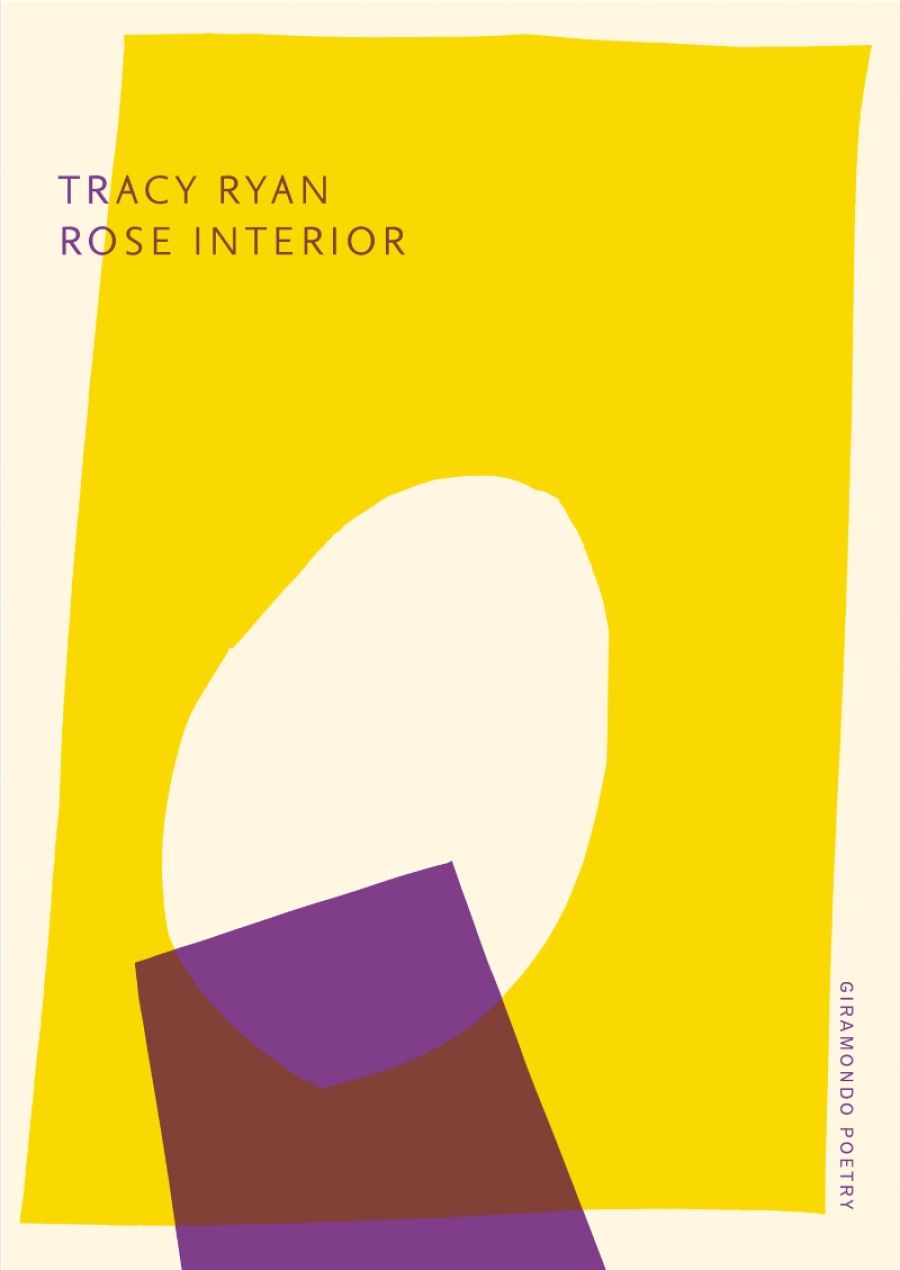

Australian writers, like most artists, live in a precarious financial situation. Australia Council funding for Australian literature was recently cut by the Morrison government by forty per cent, reducing it to a paltry $5 million a year. That’s hardly a platform from which to relaunch an Australian literary resurgence.

Emerging writers, some of them potential prize-winners, find themselves having to work full time to meet the cost of living and attempting to eke out a second or third novel in the hours left to them after a full working week and household responsibilities. Penury is not a recipe for developing a strong literary culture in Australia. Professional writers need time to hone their craft. That’s how the Labor government needs to treat Australian writers who have established themselves as strong early talents.

Fund the Arts would like to see five policy changes to help Australian writers.

During the 2022 federal election campaign, Fund the Arts pushed for Creative Fellowships for talented artists from across the arts disciplines. A modest annual income of $85,000 for three years would allow 300 talented Australian artists to hone their craft and to build an audience for their work.

A second is for government to help promote and sell Australian art (films, music, theatre, visual art, and books) overseas in much the same way the Australian government helps find markets for beef, wine, and cauliflowers. With the right level of energy and investment, we could see a cultural renaissance for Australian stories.

The third policy that would provide a greater reward and opportunity for Australian writers would be to expand the Electronic Lending Rights and Public Lending Rights scheme to include digital. We would like to see that budget doubled to $46 million per annum. More money for translation of Australian novels into other languages and their marketing overseas would also expand the market and remuneration for Australian writers.

The fourth is copyright and intellectual property reform. Novelists and screenwriters need to be better remunerated for the work they produce, especially when a work is adapted for screen. We’d like to enshrine the right to fair remuneration for authors, commensurate with the success of their work.

The fifth policy area we’d like to see change in is funding for our tertiary training sectors that help develop the next wave of Australian screenwriting and novel writing talent. Talent doesn’t drop from the sky: it has to be nurtured and mentored, through greater funding and closer ties with industry.

David Latham is the campaign manager and lobbying strategist for Fund the Arts.

This is one of a series of politics columns generously supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.

![]() Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Want to write a letter to ABR? Send one to us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

%20crop%20copy.jpg)