- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Custom Article Title: Three bold new short story collections

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Strange and unfamiliar terrain

- Article Subtitle: Three bold new short story collections

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

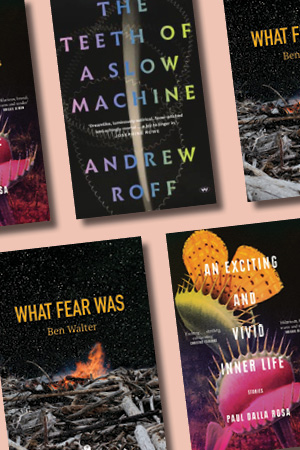

In the wake of other recent compelling débuts – Paige Clark’s meticulously crafted and imagined She is Haunted being a standout – three new short story collections, varying markedly in tone, style, and setting, offer bold and unsettling visions of twenty-first-century life.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Anthony Lynch reviews 'The Teeth of a Slow Machine' by Andrew Roff, 'What Fear Was' by Ben Walter, and 'An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life' by Paul Dalla Rosa

Yet it is the mechanical nature of behaviours and external forces that drives many stories in this collection. The title is drawn from a description of jagged cliffs met by ocean in the second story, ‘Pigface’, where an island tour guide is bound by her employer’s rigid rules as well as by sea. Elsewhere, the ‘machine’ takes on a literal aspect, as in ‘Early Adopter’, in which the narrator, Icarus-like, purchases wings that enable flight; and ‘Else/If’, written in a programming code of comments and inputs that assesses the likelihood of surviving the ‘pandemic-du-jour’.

‘Science gave her what she needed’, we learn in ‘Leibniz and Newton Take the Train’, which holds true for many characters here. So, for example, in ‘The Mind–Body Problem’, a researcher – with the demeanour of an old-fashioned, white-coated boffin – detachedly studies human subjects bearing a striking resemblance to those cruelly detained in Australia’s offshore detention centres.

Quieter stories are among Roff’s best. ‘A House, Divided’ articulates the physical division of a house by a sadly divided couple. In ‘Third Heaven’, the protagonist lives a kind of afterlife in a situation only gradually, but movingly, revealed. From there, the collection evolves rewardingly. ‘Reality Quest’ offers a wry online gaming script set in medieval times in which the gamer’s ‘progress’ becomes ever more dire. ‘Camelopard’, in which the protagonist merges with his team mascot alter ego, underlines the collection’s established themes with an inspired portrait of loyalty and servitude.

Building in imaginative and emotional impact, many of Roff’s stories have a touch of J.G. Ballard – and that’s no bad thing.

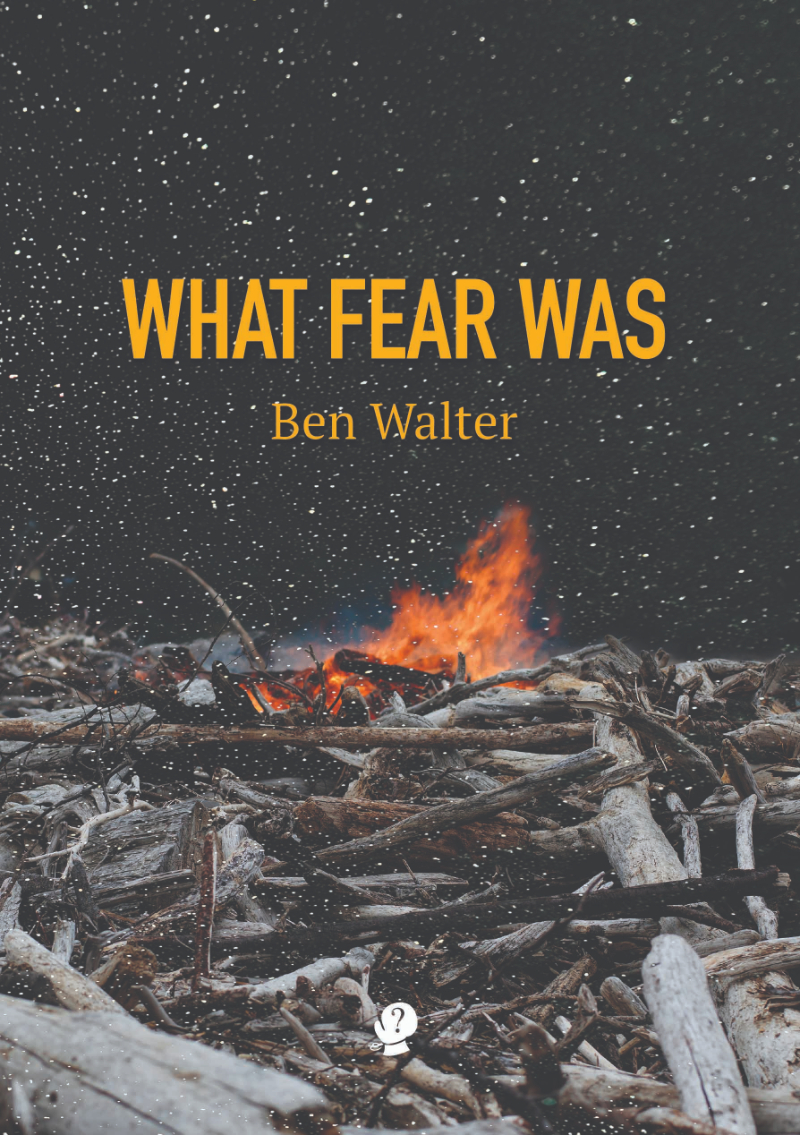

What Fear Was by Ben Walter

What Fear Was by Ben Walter

Puncher & Wattmann, $29.95 pb, 174 pp

Ben Walter’s What Fear Was traverses what one story calls ‘Strange and unfamiliar terrain’. We enter a world where doomed fish address a human, the dead warn the living, and hikers literally and metaphorically struggle for a foothold.

Landscape – most often Walter’s native Tasmania – emerges in rich and intimate detail, yet remains unknowable. Settings possibly recur across stories, but it’s difficult to be certain. And that, perhaps, is the way it should be. Disorientation looms large in these imaginatively constructed narratives. Like the bamboozled bushwalker, can we be sure we’ve hiked this track, visited this hut before? Could we find it again?

The title story is a one-paragraph, two-sentence, three-page wending through landscape that’s as much prose poem as story. A boy and girl set out ‘to learn what fear was’. A bushfire approaches, but as he does elsewhere, Walter neatly sidesteps melodrama. Despite the sense of foreboding coursing through the long, breathless sentences, the two hikers – in denial and conversing with fleeing animals – continue. Counterpointing their journey through ‘the argument of mountains’ is an unidentified ‘us’, on safer ground but knowing peril: ‘we are fearful, we are scared’.

Fear – unspecified, unnamed, and countered by narrative and perspectival play – informs much of this collection. The voice that repeats ‘we’ll be alright’, ‘it’s going to be fine’, becomes a mantra for all that is not fine, for when you have ‘wondered off the route’ and ‘your breath is a poor and fading engine’ (‘Wrapped in Ice, Speaking’).

Lest this seem like an unrelenting slog through hostile terrain, stories such as ‘We are All Superman’ and ‘It’s all Happening Here’ (in which the late cricketer and commentator Tony Greig is seemingly back to life) offer light relief, albeit with the former story’s mixed and menacing endnote.

The extended realist story ‘Conglomerate’ is a superb poetic set piece. A group of friends go hiking together. They have done so for years, and are experienced walkers. One hiker muses, presciently, over what it would mean if one of them should die. The title alludes to this tight-knit group but also to the rock that will undo one of them. By story’s end we see the figures as if from a distance, engulfed in the landscape they love and which, in so many ways, claims them.

Unafraid of ventures into uncertain landscape and innovative form, Walter’s is an impressive, sure-footed début.

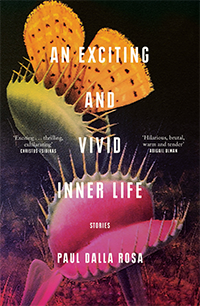

An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life by Paul Dalla Rosa

An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life by Paul Dalla Rosa

Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 220 pp

Unlike Roff and Walter, Paul Dalla Rosa remains in realist mode in An Exciting and Vivid Inner Life. But for Dalla Rosa, ‘the real’ is disturbing enough. The worlds of high-rise Dubai, hypercapitalism, menial work, retail, Amex cards, and online sex prove both immersive and alien.

The typical Dalla Rosa protagonist – often also narrator – is young, gay, male, single or in a disintegrating relationship, short on funds, impulsive, wrestling with near-addiction (alcohol, phones, sex), vain, delusional, and uncertain of his (occasionally her) future. Unreliable, given to misleading others (‘I lied but only about the things everyone lies about’), most often they deceive themselves.

These stories of stalling ambition are sharp, dark, and darkly funny. Beneath a very flattened, deadpan humour, they are also profoundly sad. The opening story, ‘The Hard Thing’, sees a young Melbournian living a dissolute life in Dubai following a split with his ex. Elsewhere, a staffer keeps a precarious hold on his management of an ultra-cool clothing store (‘Comme’); a young man stumbles back and forth between the confines of his apartment and the pancake parlour at which, failingly, he works, being ‘overly enthusiastic in the way most people mistook as mild developmental problems’ (‘Short Stack’); and another has travelled to the Gold Coast convinced that fame awaits him: ‘I focused and visualised myself surrounded in bright, flashing light’ (‘The Fame’).

Characters observe themselves as if from afar. This can manifest as vanity (‘I was pretty … My body was the kind of body that things were designed for’), but also as if they are watching themselves perform in ways in which they excel but which threaten to unravel.

These stories eschew off-the-shelf victimhood. Even in a city such as Dubai, where non-heterosexual relationships are deemed criminal, protagonists largely proceed in undoing themselves through sad, vainglorious quests for recognition. ‘In Bright Light’, the final story, provides a telling counterpoint, seeing a Los Angeles-based actor ‘between jobs’ who, as a female victim of abuse who classically cops the blame, seems destined to remain between jobs for a long time.

Conveyed in short, remarkably punchy sentences, this brilliant collection reveals sometimes tragically capricious and mercurial characters whose aspirations are exciting and vivid, and whose inner lives approach the void.

Comments powered by CComment