- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Reclamation

- Article Subtitle: An affecting memoir of loss and change

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

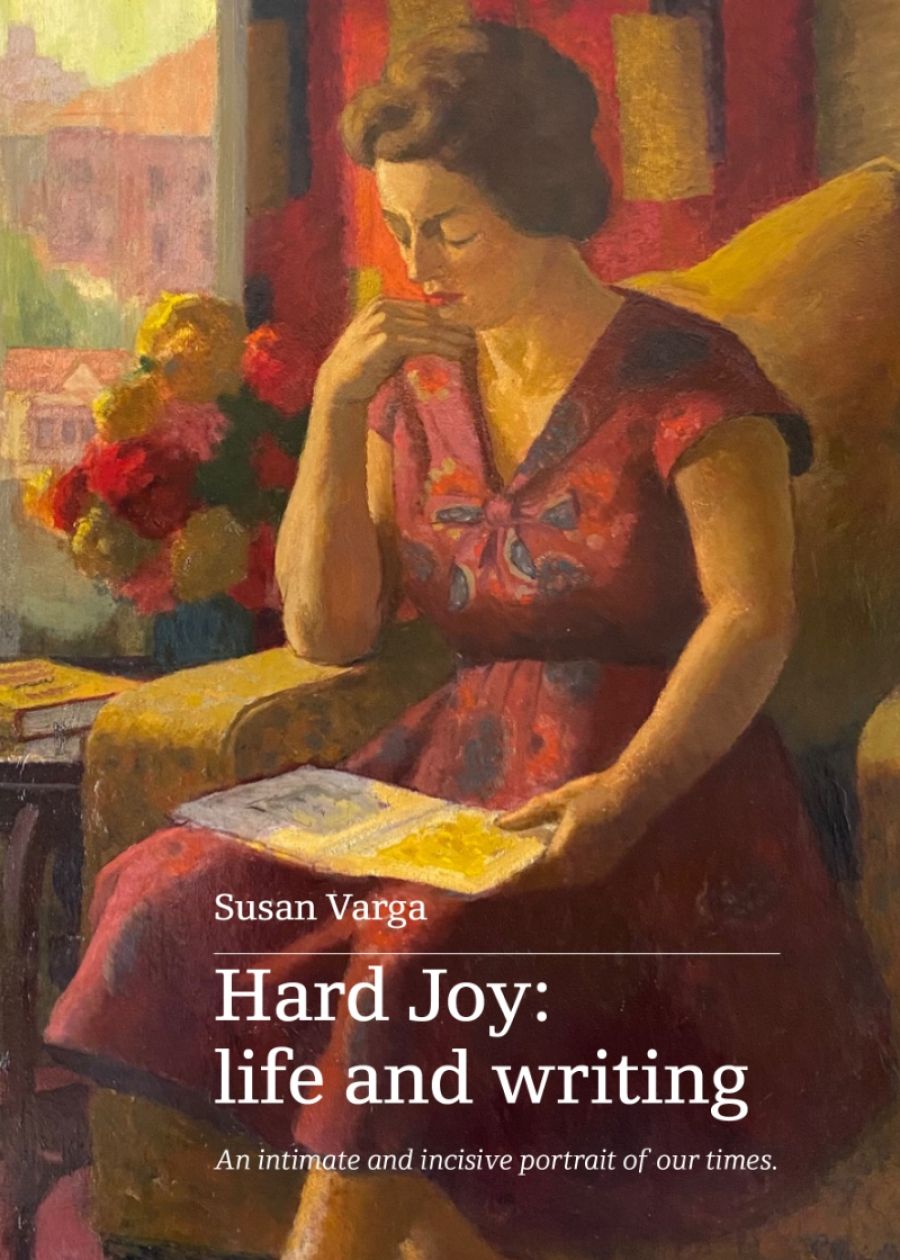

When Susan Varga made the momentous, long-delayed decision to commit herself to writing, her first task was to write her mother’s story – that of a Holocaust survivor who migrated from Hungary to Australia with her second husband and two daughters in 1948, when Susan was five. That story, which is also one of a complex and difficult relationship between mother and daughter, became the award-winning Heddy and Me (1994).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Sheridan reviews 'Hard Joy: Life and writing' by Susan Varga

- Book 1 Title: Hard Joy

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life and writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Upswell Publishing, $29.99 pb, 371 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/NKV75O

The author, in her mid-forties, had already lived a full if tumultuous life without any clear sense of purpose. The decision to become a writer coincided with – indeed, she suggests, was made possible by – forming a relationship with the woman who was to be the love of her life, journalist Anne Coombs. Varga recounts with a comic touch the scene where she admitted this desire to give up her practice as a barrister in order to write: on a road trip she requested a mid-morning stop at a country pub; in a conversation over drinks in the hallway (for privacy), she made her stammered confession, fearing it would be met with scorn or even anger. ‘Is that all?’ said Anne: ‘So when are you going to start?’

At mid-life Varga had made ‘landfall’, as she names the third section of this memoir. She had found her purpose in writing, and ‘felt for the first time that I was embarking on life with a partner in every sense’.

Hard Joy has four sections: Bearings, Tumult, Landfall, and Fate. But first, a brief prologue revisits the events told in Heddy and Me: the perilous early months of Susan’s life, hidden with her mother and grandmother in a village during the last years of the war; then a few years back in Budapest before the communist regime prompted the re-formed family to leave, their passports stamped ‘never to return’. The story is told in the present tense, in short, sharp scenes.

Part I, ‘Bearings’, follows Susan through childhood and troubled adolescence (less obvious reasons for this trouble emerge later in the narrative), rebelling against not only her parents but also the middle-class life they aspired to.

The book’s cover invites us to read it as ‘an intimate and incisive portrait of our times’. As a contemporary of Susan Varga, I enjoyed her evocation of student days at Sydney University – the brilliance of theatrical performances like John Bell’s Coriolanus or Germaine Greer’s Mother Courage (I remember Greer in ‘Revue of the Absurd’), as well as the mystique of The Push (which I observed warily, but of which Susan was one of the stars). Nostalgic bells rang as I read her stories of travelling overseas without a care in the world for establishing a career or settling down. Her accounts of feminist activism during the Whitlam years, of setting up a women’s shelter, of making videos and collective living, also resonated with me.

Yet the memoir she has produced chooses not to focus on the political and social contexts of our times, but has a more inward perspective. It’s a book about a woman claiming and reclaiming the power to shape her own life. The narrative is pared back: it frequently opens out into poems and photographs, but ‘skims through vast stretches of [her] life-landscape’, only pausing longer to explore experiences she characterises as ‘personal mountains’.

In Part II, ‘Tumult’, looking back on ‘the most tumultuous and vivid years of my life’ in the early 1970s, Varga expresses dismay: at her marriage to ‘the Dutchman’ falling apart, the ‘half-arsed and random affairs’, the succession of people and jobs. ‘I am amazed that with my personal life in such disarray, I functioned at all,’ she concludes. Then with the sudden end of that period of intense political change, she retreated from that communal life into a long, unsatisfying relationship with another man, during which she studied law and began practice as a barrister.

Part III, ‘Landfall’, tells of the life that she made with Anne Coombs, a life rich with writing, travel, country living, activism, and philanthropy. As well as their individual books, together they researched and wrote the controversial Broometime (2001). They set up the successful community advocacy group that became a network, Rural Australians for Refugees. Later, they would establish a foundation to fund social justice projects, which they ran for ten years.

The final section, ‘Fate’, recounts several cruel breaks in this life: first, the deaths of Susan’s parents, followed by Heddy’s last, fatal gift to her daughter. Susan’s struggle to accept her mother’s suicide fed into her novel, Headlong (2009). Then came another traumatic break. In 2011, in her late sixties, she suffered a severe stroke. She ‘lost her words’ (as a friend of mine said of this experience), and it took her years to reclaim them. Returning to writing, she tried poems, and they accumulated until she had a book ready for publication, Rupture (2016). This was a long, hard struggle, where she almost lost her beloved, along with her best self. The title, Hard Joy, is exact. As she writes in the epilogue:

I had no idea how rocky the road to ageing would be … But nor did I expect to have to dig so deep to find new, essential skills to survive until death finally takes me … Even here, at this stage, joy can be found and mined. Maybe the hardest joy.

As I was finishing this review, I looked up Anne Coombs to see what books she had published, and was shocked to learn that she had died some months ago – another cruel blow for this courageous woman, Susan Varga. What she has achieved in Hard Joy is a heroic act of reclamation, and what she shares in this memoir is immensely moving.

Comments powered by CComment