- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Decisions of untold consequence’

- Article Subtitle: The uses and abuses of history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

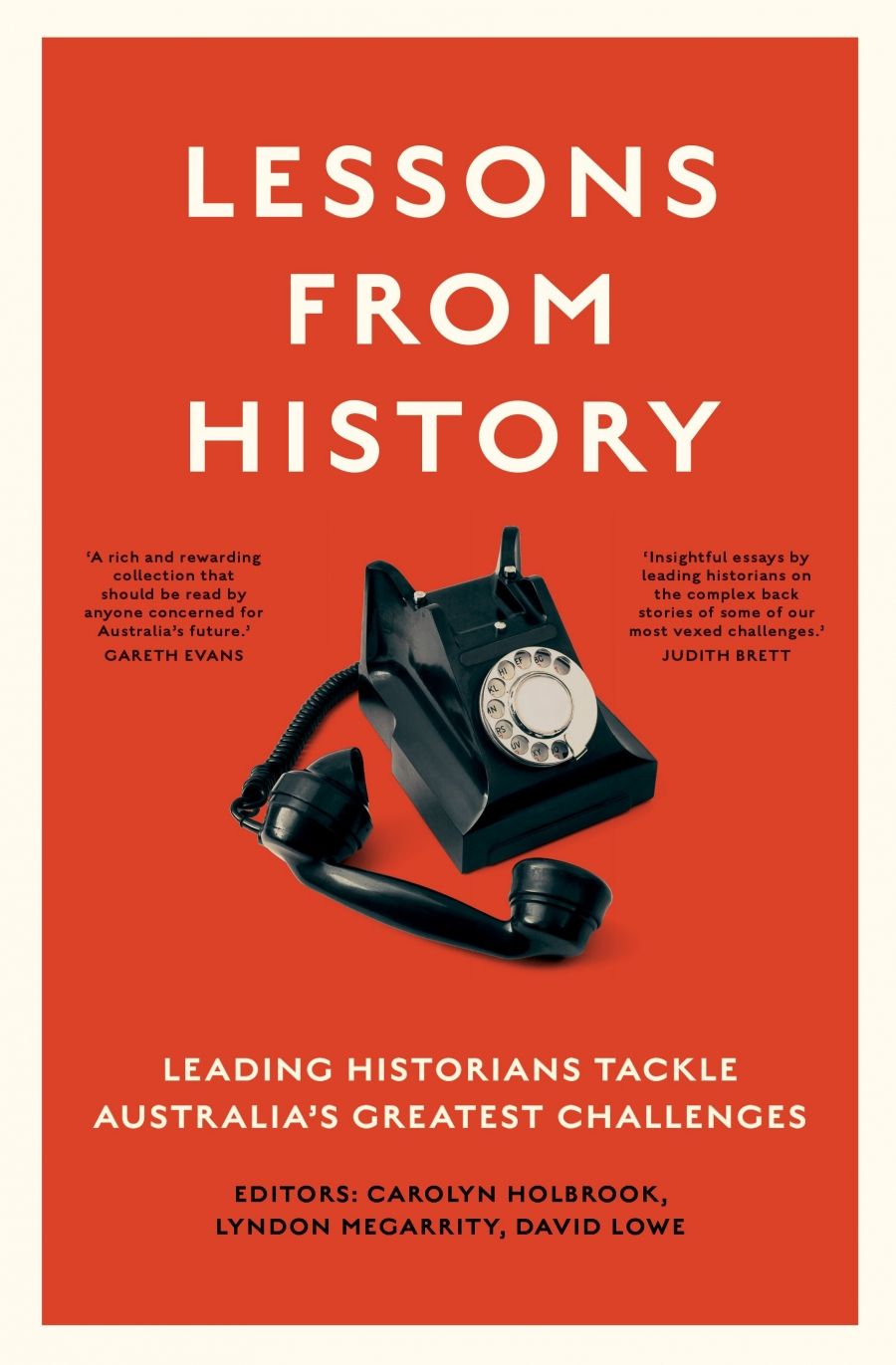

Lessons from History is a big, ambitious book. Its twenty-two essays – amounting to some 400 pages of research, reflection, and references – seek to pin down, in accessible form, the combined expertise of thirty-three practitioners of history and related fields. Together they address a mélange of pressing issues facing Australia today, testament to the diversity of contemporary Australian history and its interdisciplinary reach. Political, social, economic, business, environmental, and oral historians are all represented, alongside authors whose institutional base is in strategic studies, economics, politics, or administration, but whose work is informed by a keen interest in the past and its lessons.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Penny Russell reviews 'Lessons from History: Leading historians tackle Australia’s greatest challenges' edited by Carolyn Holbrook, Lyndon Megarrity, and David Lowe

- Book 1 Title: Lessons from History

- Book 1 Subtitle: Leading historians tackle Australia’s greatest challenges

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 416 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/b3eYxk

It is a big book and a timely one, for we live in troubled times. Climate catastrophe is now visibly upon us; decades of neoliberal government have shredded social welfare and created a society of gaping inequalities; international tensions are on the rise and so, too, is right-wing extremism at home and abroad. Facing such intractable problems in a volatile world, argue the three editors, our politicians and policy makers ‘need at their disposal the best information in order to make decisions of untold consequence’. That ‘best information’ includes historical research and the power of historical thinking. So the editors issue a ‘call’ to both historians and policy makers: the former are urged to ‘make their voices heard in the public forum’, while the latter are ordered to listen.

Since it is a timely book, I wish the editors had taken a little more time over its preparation. With more careful editing of their own text, they might not have veered so unsettlingly between rousing calls to arms (‘We will not stand by while the stumps of democratic governance are white-anted’) and strangely modest claims (‘Rich context is a desirable ingredient in good policy’), sprinkled with the occasional descent into incomprehensible jargon (‘a roadmap for this vital knowledge’) and some lyrical but oddly misplaced metaphors (‘Like a soft but insistent bass, history thrums the rhythm of human experience’). Clarity comes a poor second to rhetoric, which is not a good advertisement for the product and makes the tub-thumping conclusion (‘Policy-makers must listen’) less convincing than it should be.

The editors might also have done more to resolve the curious slippage noticeable between the feisty aspirations of the editors themselves and the more cautious pronouncements of their contributors. Part I, confidently titled ‘How a Knowledge of History Makes Better Policy’, contains three essays by historians keen to qualify that premise and invest it with nuance. Scholars and policy makers may agree that history ought to have lessons for the present day, writes Graeme Davison, but ‘they are unsure about what they are’. Only occasionally will historians ‘be in the room where the big decisions are made’ – but they write the books and lead the debates and, most importantly, educate the decision-makers to think historically. Interpreting the past may offer ‘clues and insights’, notes Frank Bongiorno, but it rarely presents clear ‘lessons that can be mechanically applied’ to the present. Nor are politicians always keen to learn the lessons of history, often wanting instead to rewrite it for their own purposes.

Our ‘only hope’ in the struggle to prevent misuse of the past, Bongiorno concludes, ‘might be to work to increase historical literacy from the ground up’ – that is, to build and defend a critical history curriculum in schools and universities, informed by the best scholarship. James Walter writes that historians should grasp any opportunity to influence the policy domain or mobilise community opinion, but emphasises that their work is also to create ‘constituencies for change’ – to break ground and change minds through the cumulative build-up of research (and, I would add, of teaching).

All three essayists, then, write thoughtfully and probingly about the moral and social imperative upon historians to bring their expertise to the service of a wider audience, but all see their role as broadly educative rather than narrowly advisory. Perhaps conscious of this mild subversion of their vision, the editors at one point repudiate their own title, assuring us that they are ‘far from seeking to offer crude historical “lessons” or rigid templates that might be imposed upon contemporary problems’. But the structure of the book, in which each essay concludes with a section titled ‘Lessons from History’, tells a different story.

What, then, are these lessons? Part 2 comprises nineteen ‘case studies’, which address an eclectic mix of policy issues. Their status as case studies may excuse the rather partial coverage of the big issues of the moment, but I still wanted to know more about the reasoning behind the selection of these particular essays, themes, and contributors. The introduction gestures in a large way to various ‘wicked’ problems, not all solvable at national level and some defying solution altogether. Climate change, the increasingly bellicose tone of international relations, and the threatened collapse of democracy in the United States head the list; there is mention also of wealth inequality, and whispers of a pandemic. But despite the headlines, these issues get surprisingly thin treatment in the body of the book – honourable exceptions being a hard-hitting and compelling essay from the team of historians (Andrea Gaynor and others) addressing Australia’s water policies, which should be essential reading for everyone living in Australia today, and some sobering, cautionary words from Hugh White on the dangers of relying on ‘lessons’ from histories ‘encrusted with tradition, sentiment and ideology’ as we face the challenge of a rising China.

From the less heralded essays that follow there is much to be learned, on such diverse topics as foreign aid, multinational companies, Aboriginal self-determination, Australia’s refugee and migrant policies, domestic violence, memories of the Great Depression and lessons from post-war reconstruction. I admired Mia Martin Hobbs’s analysis of the ideologies, strategies, and prejudices in military culture and wider society that shape war crimes and shield their perpetrators; and enjoyed Evan Smith’s punchy, thoughtful analysis of the historical success of collective action in combating racial hatred and the far right. Readers will find their own favourites, for there is plenty of insight and probing analysis to be found between the covers of this rich, eclectic collection.

It all goes to justify the editors’ contention that historians have much to offer the world of public debate and policy making. But I am not convinced they always need to be ‘in the room’ to do so. There are skilled practitioners out there – journalists, educationists, think tanks, policy researchers – whose task it is to do the work of assimilation, translation, and application. To do that work well, they need the best works of engaged scholarship that historians can produce, and the skills to put those resources to practical, cultural use. Scholarly historians (not only those who study recent Australian history, but those whose understanding of the past and human society extends more deeply into time) may achieve their greatest impact when they teach their students – our future policy-makers, teachers, and citizens – to wield the skills of the discipline, empowering them to think critically and knowledgeably about the uses of the past, and to question flawed historical narratives invented to justify flawed policy. No amount of expert advice from historians will prevent politicians from abusing history whenever it suits them to do so. We need an educated citizenry, who will know when they are doing it.

Comments powered by CComment