- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: No stranger to sacrifice

- Article Subtitle: Eda Gunaydin’s début essay collection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

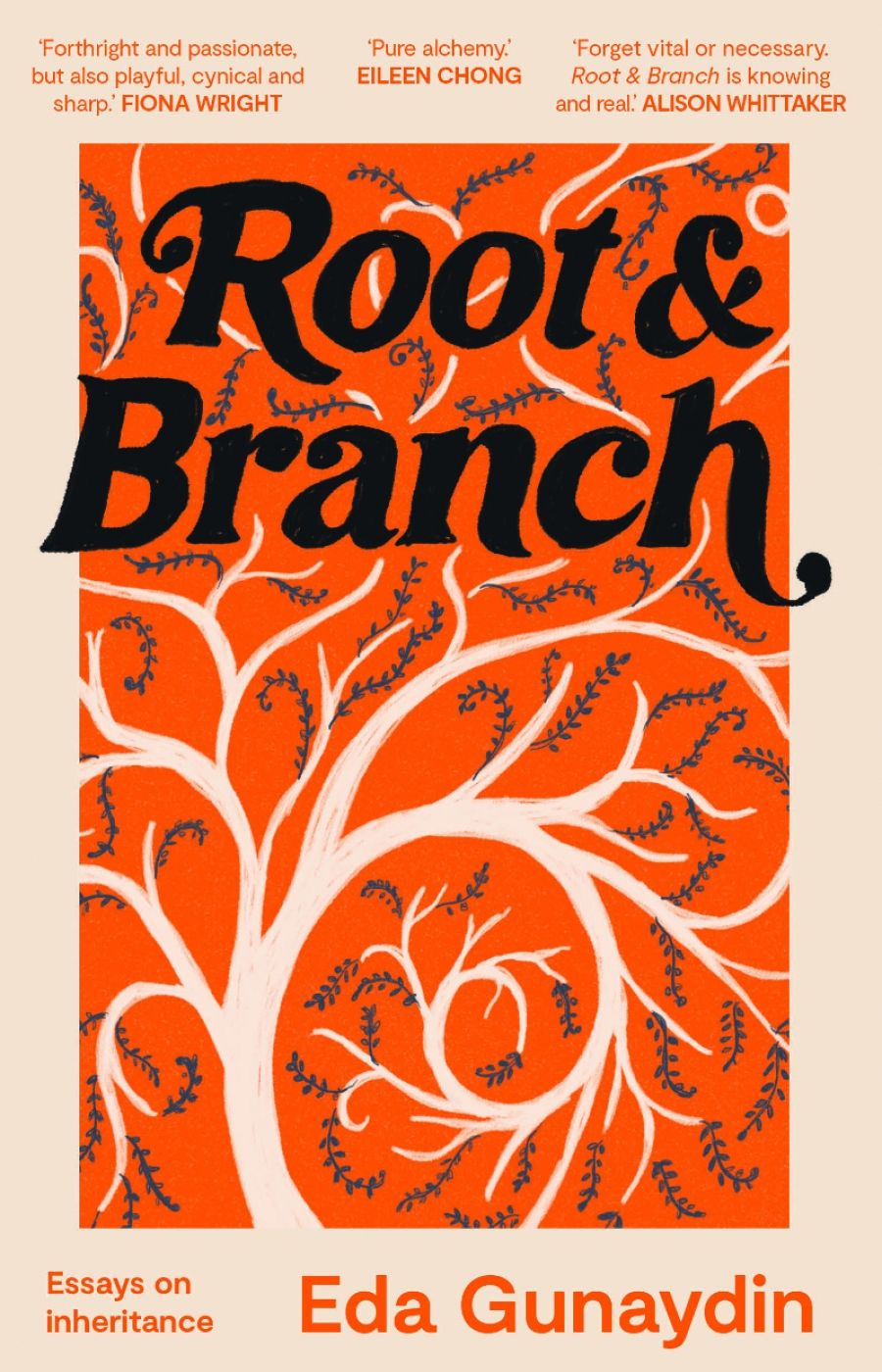

Eda Gunaydin’s collection of essays, Root & Branch, centres on migration, class, guilt, and legacy. It joins the surge of memoir-as-début by millennial writers, who interrogate the personal via the political. Gunaydin, whose family immigrated to Australia from Turkey, grew up in the outer suburbs of Western Sydney – home to a historically migrant and working-class demographic. We learn that her father, a bricklayer, has been the household’s sole income provider as the health of her mother, Besra, meant that she ‘never had a job in this country except cleaning’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Mindy Gill reviews 'Root & Branch: Essays on inheritance' by Eda Gunaydin

- Book 1 Title: Root & Branch

- Book 1 Subtitle: Essays on inheritance

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $29.99 pb, 278 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/mgBY6M

Besra ensures that her daughter is no stranger to sacrifice. She tells her repeatedly that ‘[i]f anyone should be unhappy, it’s me’. She is the kind of figure who would delight readers if she were a character in an Elif Batuman novel, but Gunaydin reminds us that real-life mothers differ from fictional ones. In the moving essay, ‘Literacy’, she describes a series of encounters with her mother that range from the painful to the cruel. What is profound is how she’s able to do so with the kind of tenderness, or pity, earned from parenting one’s own parent. This ability to write about trauma without withholding empathy is indicative of how wary, even paranoid, Gunaydin has become about ‘reproduc[ing] cycles of abuse’. Nonetheless, Gunaydin can be remarkably self-effacing, a quality that enriches her faculties for human observation. It allows her to describe almost everyone but herself with curiosity and compassion. This includes the people who mistreat her, or dismiss her for being ‘a chubby, crooked-toothed, glasses-wearing nerd’; it seems that Gunaydin isn’t afraid that anyone will think worse of her than she already thinks of herself.

Gunaydin’s métier is the confessional. She spends an essay attempting to pathologise this penchant for self-disclosure and its prevalence in our culture. The piece exemplifies both the strongest aspects of Gunaydin’s non-fiction as well as those that are less successful. She confidently places herself at the centre of her own study, using her own experiences to understand why people long so insatiably for ‘new ways of being seen’ by dedicating hours to BuzzFeed quizzes, personality tests, and schema therapy questionnaires. For the most part, she trusts that her own self-searching will lead her towards greater clarity, and refrains from using external sources to validate, and inadvertently sterilise, her experiences.

Elsewhere, this book tends to lean heavily on cultural theory. There is a plethora of quotes. This can be a reflexive habit for academically trained writers, for whom demonstrating one’s knowledge is a prerequisite for advancing any claims. But, rather more, like the critic who relies on literary associations to insist on his authority, the practice comes across as intellectual insecurity. These instances of exposition are most prevalent in the first half of the book, where political messaging – about capitalism, Marxism, and anti-racism – is at the forefront. Here, Gunaydin becomes too self-effacing, leaving readers with the impression that she lacks the confidence to assert her own ideas. This overreliance on theory could also be symptomatic of the pressure some non-fiction debutants face. A writer might feel compelled to legitimise the act of speaking publicly about their life without the rationale of age or a life-changing event. I think of a vignette in Root & Branch where Gunaydin flinches in front of her mother, who in response angrily jabs: ‘Who abused you?’

When Gunaydin isn’t trying to prove a point to her readers, but is instead seeking some clarity of her own, then these essays become wonderfully probing, surprising, and wry. She is at her most original when writing about illness. She drops the academic façade as she takes us into her inner life, becoming exploratory, associative, and self-assured. She remarks blithely, in an essay about the precarious employment of a beloved professor, that perhaps her fascination with his opaque and singularly entertaining lectures was a ‘diversion … to belay [her] own suicide’.

Gunaydin’s voice and startling confessions are the strengths of this book, yet the ordering of these essays doesn’t do it justice. The collection’s second half is by far the more compelling, as it is in these pieces where the writer allows herself the freedom to explore her own ideas, rather than explicate another’s. A number of the earlier essays in Root & Branch summarise key theories about class, race, and labour, but exclude Gunaydin’s perspective. While she establishes her alignment with these beliefs, she fails to engage them with any rigour, leaving the reader with an odd sense that she is reluctant to argue any specific point of her own. Coupled with her tendency to immediately defuse her critical assertions, it can make an otherwise compelling essay feel suddenly lukewarm. In ‘Second City’, she writes uncompromisingly about a stint as an arts producer in Parramatta, and her disillusionment when the role transpired to be in aid of the suburb’s gentrification. However, instead of continuing to examine this phenomenon – where encouraging the ‘centre’ to explore the outer suburbs is prioritised over meeting the needs of its own residents – she cuts herself short, qualifying that the problem is ‘only emblematic of the underlying, structural issues which impact the entire arts sector, and for which no individual organisation is culpable'.

Gunaydin does not need to build ideological scaffolding to hold her essays up. When she writes of her mother’s experiences with chronic pain in ‘Live On’, and of her own experiences receiving care in an understaffed public hospital in ‘Western Medicine’, we recognise that this scholarly material only obscures her talent. It stymies the depth of intimacy she otherwise creates so adeptly. Readers of Root & Branch may finish this inquisitive book thinking that it is not Lacan’s, or Said’s, or Kristeva’s ideas that keep them turning each page, but Eda Gunaydin’s.

Comments powered by CComment