- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Delible impressions

- Article Subtitle: Liberating Daisy Simmons

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Daisy Simmons – twenty-four years old, the wife of a major in the Indian Army, mother of two children, ‘dark [and] adorably pretty’ – is an ephemeral presence in Virginia Woolf’s fourth novel, Mrs Dalloway (1925). Clarissa Dalloway’s former lover, Peter Walsh, has travelled to London from India to secure a divorce so that he might marry Daisy. From a mere handful of references, we are able to glean the wavering nature of Peter’s devotion to Daisy and his suspicion that she will, as Woolf writes, ‘look ordinary beside Clarissa’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Diane Stubbings reviews 'Daisy & Woolf' by Michelle Cahill

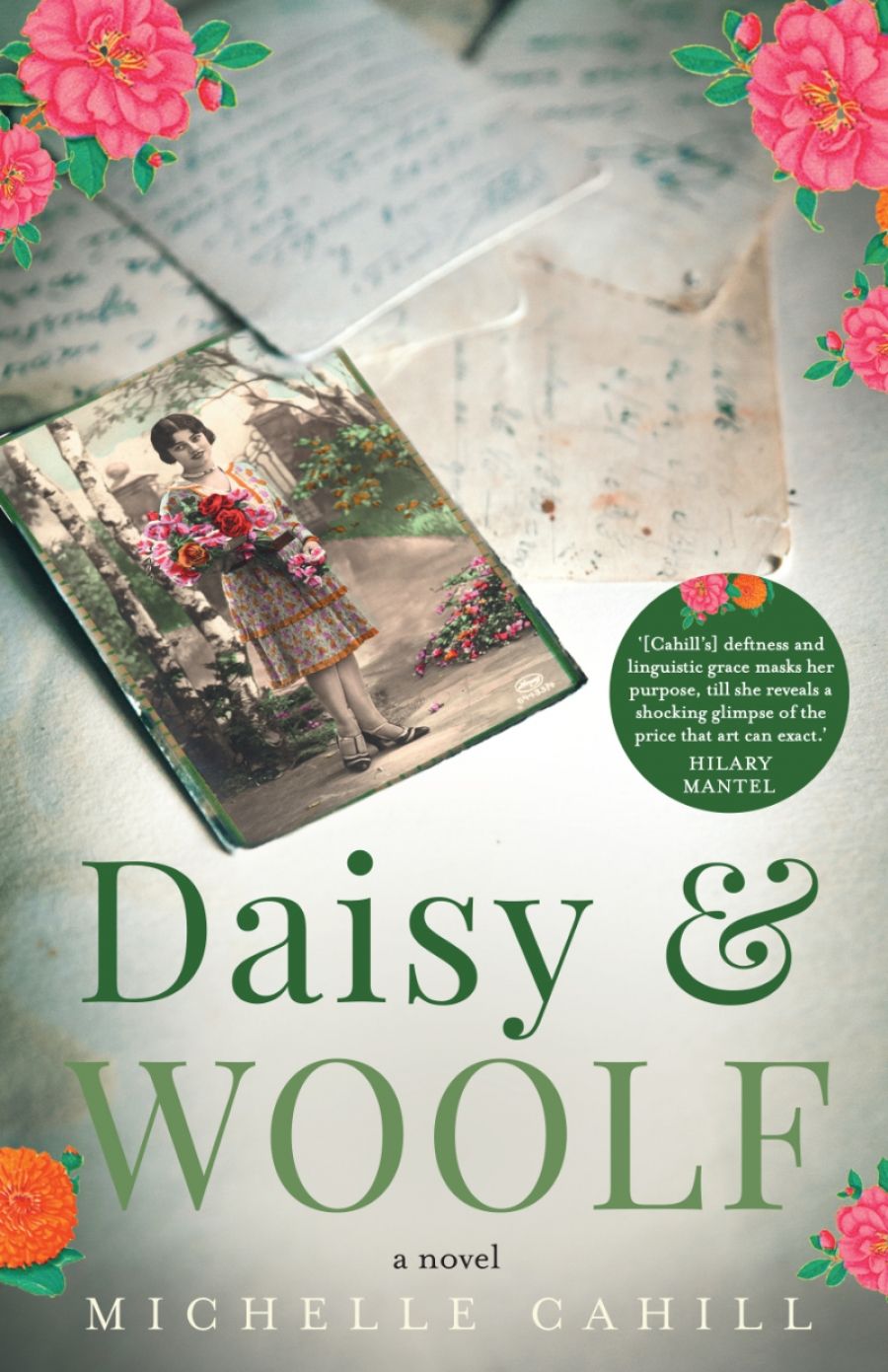

- Book 1 Title: Daisy & Woolf

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $32.99 pb, 296 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/ORJ7VG

In Daisy & Woolf, Michelle Cahill attempts to liberate Daisy from the pages of Mrs Dalloway, to furnish her with ‘an alcove of interior space to move about in, to express her ecstasy or to vent her grief’. In doing so, Daisy’s story becomes entangled in Cahill’s own struggle to channel Daisy’s ‘vibe’ and find a life for Woolf’s ‘literary half-caste’. The result is a novel that becomes more about the craft and business of writing – about the way reality and fiction curve in and out of each other like a Möbius strip – than about either Daisy or Woolf.

Cahill takes up Daisy’s story in February 1924, more than six months after the day in June 1923 that Woolf records in Mrs Dalloway. Through a series of letters and journal entries, we follow Daisy as she travels from her home in Calcutta (Kolkata) to London to be with Peter, abandoning her husband and her son, and taking with her on the journey her daughter, Charlotte, and her maid, Radhika. Once in London, Daisy accepts the role of governess in a well-to-do household while she awaits the resolution of her own divorce and her marriage to Peter.

Michelle Cahill (photograph by Nicola Bailey, via author's website)

Michelle Cahill (photograph by Nicola Bailey, via author's website)

Daisy’s story is framed by that of Mina, the writer who has taken it upon herself to give tangible form to a character who, according to Mina, Woolf has ‘scarcely sketched’. Just as Mina is nested within the experience of Cahill herself – both are Eurasian women resisting the ‘dominance of whiteness … and colonialism’ (as Cahill writes on her website) and the patriarchal and racist ‘gatekeepers’ of the publishing industry (as Mina soughs in her own journal entries) – so too is Daisy nested within both Mina’s experience of race and of leaving behind an (ex)husband and child to pursue her own destiny: ‘It sometimes feels like I am travelling in her footsteps.’

There is an argument to be made that Daisy’s virtual absence from Mrs Dalloway is a necessary indication of how tangential she is to the lives of Peter and Clarissa rather than a reflection of Woolf’s imperial ‘privilege’ or her desire to ‘[use] her genius to slay Daisy Simmons’. Even setting that argument aside, for all Cahill’s attempts to rescue Daisy from the periphery of Woolf’s narrative – to disclose ‘the invisible ink in the history of cross-cultural connections’ – the irony of Daisy & Woolf is that any sense of Daisy is ultimately swamped by Mina’s repeated lamentations about the ‘hard choices’ of the writer’s life and her occasionally patronising monologues: ‘It may surprise a reader to learn that this is how a character can take hold of a writer, even to the extent of thriving at the writer’s expense.’

In what seems a missed opportunity, Daisy & Woolf denies us the chance to directly witness Daisy’s encounters with either Clarissa or Peter, the letters between Daisy and Peter reading more like the reluctant correspondence of old acquaintances than separated lovers. And there is scant insight offered into the degree to which Daisy’s race (as opposed to her class or the scandal of her adultery) affects either her social standing or her eventual fate. The only time we are jolted into acknowledging the social and political repercussions of her Anglo-Indian heritage is when she is refused the designation ‘British subject’ on her passport because her ‘skin colour is too dark’.

Cahill’s volume of short fiction, Letter to Pessoa (2016), showcased her engagement with the work of other writers, offering, in a style reminiscent of John Hughes’s remarkable collection Someone Else (2007), dazzling riffs on those writers’ oeuvres. Yet there, as here, Cahill’s efforts to extend the writing beyond an intellectual exercise, to imbue it with its own impulse, its own reason for being, can feel laboured. In Daisy & Woolf, Cahill’s engagement with Woolf’s writing tends towards the cursory, and it’s impossible not to compare the novel with To The River (2011), Olivia Laing’s transcendent contemplation of Woolf and the writing life.

‘The emergencies and transitions in my own life, through which [Daisy’s] voice has been a running thread’, Mina writes, ‘speak a story that refuses to be contained by a beginning, a middle and an end’, and this perhaps suggests something of Cahill’s purpose – to expose the chaotic underbelly of the conventionally crafted novel. What emerges, however, is a novel, and a narrator, whose self-obsession and indignation in effect deaden the very voice they seek to make heard.

In ‘Modern Fiction’, Woolf notes the ‘myriad impressions’ the mind daily receives. Cahill has certainly caught the jumble of daily experiences, the persistent alternations between the internal workings of the mind and the noise and distraction of our external reality, that feed the imagination – the politics of Trump and Brexit, the demands of family, the joy and anguish of love, the burden of grief, the colour and clamour of India, the grim-grey streets of London, the ‘trembling’ daffodils of a New York spring.

Woolf, however, goes on to observe how such experiences might shape themselves into the narrative of a life, what T.S. Eliot refers to as a new compound forming from ‘numberless feelings, phrases, images’. In the end, this is what Michelle Cahill fails to do – to assemble all these keenly rendered impressions and experiences into a novel of consequence.

Comments powered by CComment