- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An adventurous nature

- Article Subtitle: A writer’s life through her own eyes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Katharine Susannah Prichard is one of those mid-century Australian literary figures like Vance Palmer whose name is mentioned in literary histories more often than her books are read. As it happens, she was a schoolfriend of Vance’s future wife, Nettie, née Higgins, who became a distinguished literary critic, as well as of the pioneering woman lawyer Christian Jollie Smith, and Hilda Bull, later married to the playwright Louis Esson. All were politically on the left as adults, and Prichard and Jollie Smith joined the Communist Party. It was the distant Bolshevik Revolution in October 1917 that converted Katharine to the communist cause; she was a communist in Western Australia before there was a party there for her to belong to.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

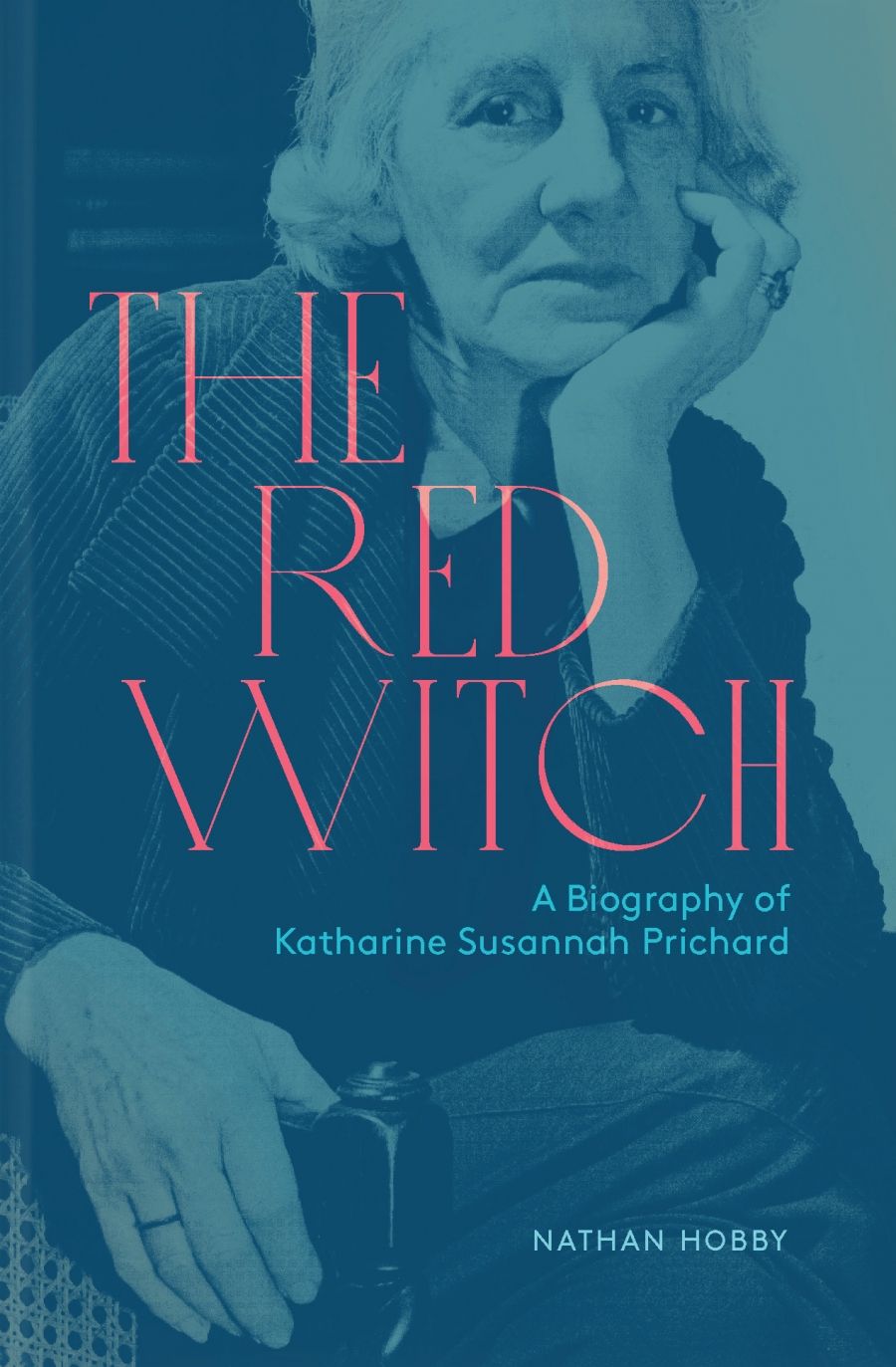

- Article Hero Image Caption: Katharine Susannah Prichard, <em>c</em>.1927–28 (photograph by May Moore, State Library of New South Wales)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Katharine Susannah Prichard, c.1927–28 (photograph by May Moore, State Library of New South Wales)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sheila Fitzpatrick reviews 'The Red Witch: A biography of Katharine Susannah Prichard' by Nathan Hobby

- Book 1 Title: The Red Witch

- Book 1 Subtitle: A biography of Katharine Susannah Prichard

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $49.99 hb, 462 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Gj57LL

Born the daughter of a peripatetic Australian journalist in Fiji in 1883, Katharine early showed an inclination to write, as well as an adventurous nature. Her youthful stints as a governess in the small regional town of Yarram in South Gippsland, and then on a sheep station in north-western New South Wales, introduced her to regional Australia and provided the raw material for her early novels, The Pioneers (1915) and Black Opal (1921). She travelled internationally, too, spending time in the mid-1920s in London, Paris, and New York. This was partly an offshoot of her affair with the older married man she called her Preux Chevalier. While Prichard would never identify him, Hobby deduces that he was probably Lieutenant-Colonel William Thomas Reay, a newspaper editor, politician, and military officer who was Katharine’s boss when she was working at the Herald in 1909–10. Hobby emphasises Reay’s possessiveness, but the affair could also be seen as a boon for Katharine as an independent woman, in that it brought her interesting experiences without tying her down as marriage would have done.

There were other lovers, including the romantic communist Guido Baracchi. But the man she married, Hugo Throssell, was a decorated and damaged World War I veteran from a good West Australian family, honoured with a Victoria Cross, and, before he encountered Katharine in London in 1915, not notable for any particular political views. They married in 1919 and settled at Greenmount, east of Perth in the Darling Ranges, where Throssell – who now, under Katharine’s influence, described himself as a Bolshevik – found work as a land agent and for a veterans’ committee. Their only child, Ric Throssell, was born in 1922.

The first decades of Katharine’s married life were productive ones for her writing. Working Bullocks (described by Esson in the Bulletin as ‘probably the best novel ever written in Australia’) came out in 1926, Coonardoo in 1929, and Haxby’s Circus in 1930. While there was no change in her political convictions, politics was relegated to the sidelines of Katharine’s life in these years (she described her first Communist Party conference, held in Sydney in December 1925, as a ‘thoroughly depressing and disappointing experience’).

The onset of the Depression in 1929 brought politics to the fore again; the Throssells were raided by police because of their communist activities. Like other Western leftists, Katharine was eager to learn how communism was working in practice and to acquire the authority of firsthand observation to rebut criticism of the Soviet Union. The Throssells were having money as well as marital troubles, but when Katharine’s sister came up with the fare to Europe in 1933, Katharine’s path to the Soviet Union was open. She went, evidently with Hugo’s blessing; but while she was away her husband’s financial problems and depression intensified, and in November he shot himself. Katharine learnt of this in London, on her way home from Russia, in a brief newspaper account. ‘No man could have a truer mate,’ Hugo wrote in his suicide note. For Katharine, the anguish of the loss was compounded by the fact that in Intimate Strangers, the novel she had been writing about a marriage in trouble, the Hugo-like protagonist committed suicide (she changed the ending in a later draft because it was ‘too painful’, but considered that as a result the book was an artistic failure).

What Katharine privately made of the Soviet Union is debatable, but her public response in The Real Russia (1934) was eulogistic. This might have been understandable purely in terms of her personal trauma, since Hugo, her eleven-year-old son Ric, her writing, and communism were the pillars of her life, and to lose two of them simultaneously would have been unbearable. But it was not uncommon for Western ‘fellow-travelling’ visitors to the Soviet Union in the 1930s to see much that privately disturbed them yet loyally to deny any problems when addressing the public back home. While the Soviet Union had escaped the depression that engulfed the capitalist world through its isolation from the world economy, it had troubles of its own. In the early 1930s, the state’s struggle with the peasantry over agricultural collectivisation led to a famine (whose existence Soviet media denied), and the ambitious program of rapid industrial development under the First Five-Year Plan had yet to produce results. By the late 1930s, the industrial results were coming in, but by then the nation was wracked by the self-induced crisis of the Great Purges.

Katharine was one of more than sixty Australian leftists whose visits to the Soviet Union are chronicled in a volume Carolyn Rasmussen and I edited in 2008: Political Tourists. Few of them knew Russian, and most were content to let their experiences be moulded by their Russian guides and the itinerary the state Society for Cultural Relations with Abroad offered them – or at any rate to accept their guides’ ‘socialist-realist’ perspective that admitted the deficiencies of the present but highlighted the few visible harbingers of the (planned) future. Katharine, to be sure, had more of an entrée into actual Soviet society than most through her friend and former lover Baracchi and his new wife, the sharp-eyed and cynical Betty Roland, in whose Moscow flat she stayed for a while. According to Roland’s later memoirs, Katharine – whose trip included a rare visit to the famine-stricken Ukraine, though Hobby does not mention this – was in fact disconcerted and disappointed by much of what she had seen. But neither the Soviet nor the Australian political climate allowed for nuance. It was a matter of ‘for’ or ‘against’ the Soviet Union, and Katharine had already opted for the first.

Nathan Hobby’s biography is not the place to go for analysis of Katharine Susannah Prichard’s communism or her contacts (continuing for the rest of her life) with the Soviet Union. Nor is it altogether the place to go for a reassessment of her novels, although he seems to have found some of them better than he had expected. Hobby did not come to his subject through any overwhelming interest in Prichard but because he was trying to write a novel about a fictional biographer, and this left him ‘intrigued by the pursuit of the past, the quest to tell the story of someone from their archival remains’. Instead of finishing the novel, he became his own fictional protagonist and wrote a biography, choosing Prichard as his subject. Among the archival remains at his disposal, he privileges Prichard’s own letters and writings. Thus his biographical perspective, though not uncritical, basically reflects Prichard’s own take on her life rather than, for example, that of ASIO (Prichard is not a ‘Red Witch’ in this biography, despite the promise or threat of the title) or her son (whose career as a diplomat was blighted because of his mother’s communism, and who wrote a biography of his mother as well as a later autobiography). The disadvantage of this strategy is that Prichard, unusually for a writer, was by nature neither introspective nor particularly interested in what makes people (including herself) tick: her best novels are lively page-turners, but her forte was not probing psychological depths but rather entering into the active lives of characters following various occupations, especially outdoor ones, and depicting landscape and natural environment, particularly the outback. Katharine Prichard didn’t want to dig too deeply into her own life and choices, and in his fair-minded biography, Hobby has respected her wishes.

Comments powered by CComment