- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Settler colonial dreamings

- Article Subtitle: Handmaidens of imperial and settler aspirations

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Country’ – the land of Indigenous peoples (minus their Dreamings) – is the great subject of settler-colonial art, an act of appropriation in which the dispossession of its original custodians is rendered invisible. As Jarrod Hore establishes beyond doubt in Visions of Nature, it was landscape photographers who proved to be one of the more significant cultural agents of settler colonialism across the Pacific Rim in the second half of the nineteenth century. What his important study reveals even more clearly is just how much they and their images were shaped by the times and societies in which they worked.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

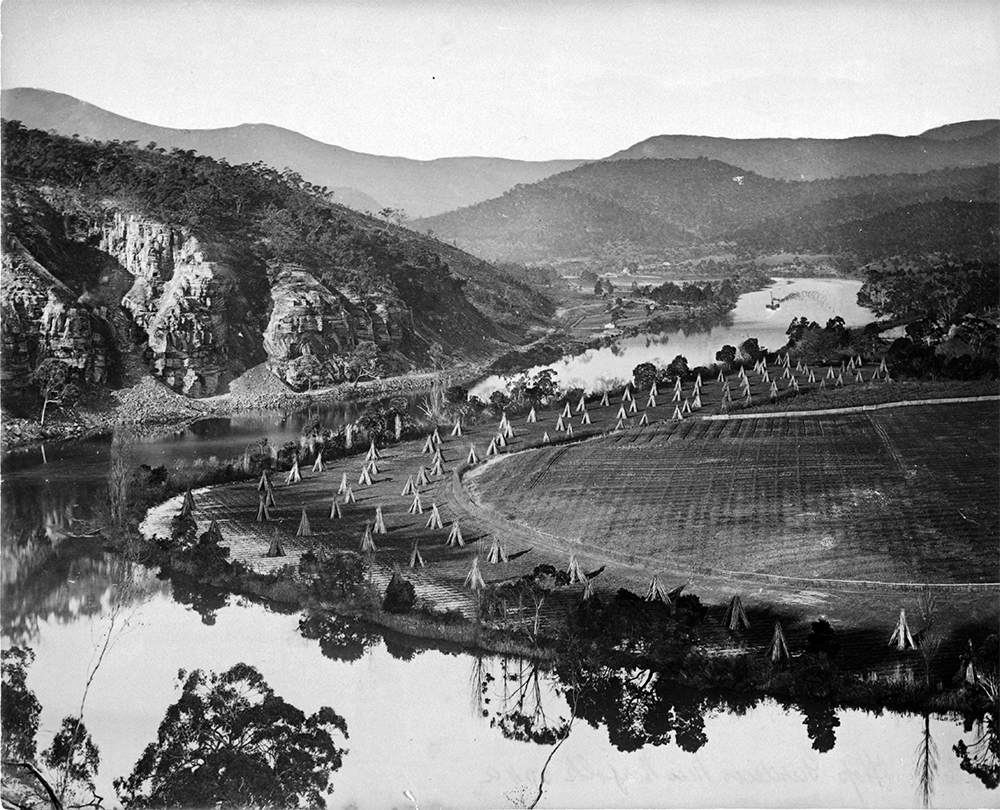

- Article Hero Image Caption: Taken less than five miles downriver from the 1836 grid, this photograph frames a harmonic interaction of settlement, agriculture, and geography on the lowlands along the Derwent River. John Beattie, <em>Hop Garden, New Norfolk</em>, 1895–98. Albumen print. Collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Accession number 202.1989.

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Taken less than five miles downriver from the 1836 grid, this photograph frames a harmonic interaction of settlement, agriculture, and geography on the lowlands along the Derwent River. John Beattie, Hop Garden, New Norfolk, 1895–98. Albumen print. Collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. Accession number 202.1989.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gary Werskey reviews 'Visions of Nature: How landscape photography shaped settler colonialism' by Jarrod Hore

- Book 1 Title: Visions of Nature

- Book 1 Subtitle: How landscape photography shaped settler colonialism

- Book 1 Biblio: University of California Press, US$29.95 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/mgBY6M

Hore’s thesis is that white settlers, between 1850 and 1900, embraced ‘a vision of nature that reinforced their territoriality at the expense of local Indigenous people’ through the reproduction of ‘photographs suffused with a possessive spatial politics’. He illustrates this argument through the work of six photographers based, respectively, in northern California (Carleton Watkins and Eadweard Muybridge), Aotearoa New Zealand (Alfred Burton and Daniel Mundy), and Australia (James Beattie in Tasmania and Nicholas Caire in Victoria). (A pair of Canadians would have nicely rounded out his survey of Anglo–Pacific settler societies.) All were British-born, save the New Yorker Watson; apart from Muybridge, all of them settled permanently in these colonial outposts. As an environmental historian, Hore is happy to cast their stories as ‘geobiographies’, emphasising how their lives became ever more entangled with the landscapes they framed. However, his narrative strategy is to braid these men’s work and careers into a larger argument about how landscape photography evolved into a powerful expression of settler belonging and Indigenous erasure.

The convergence of mid-century gold rushes across the Pacific Rim with advances in camera technologies placed these photographers on ‘the front lines of the settler revolution’. During the 1850s and 1860s, their main function was to record locales and terrains of interest to government surveyors, geographers, and geologists, as well as to mining, railway, and agricultural companies. Thereafter, the explosive growth in settler populations offered additional markets for their work to celebrate not just these territories’ ‘golden soil and wealth from toil’ but also the ‘beauties rich and rare’ of their ancient and supposedly empty wilderness landscapes. By century’s end, these photographers had established themselves as influential handmaidens of both imperial and settler aspirations through ‘a technology of settlement that brought distant spaces into colonial control’.

One of Hore’s key themes is how settler landscape photographers in the American West as well as the ‘Tasman World’ were able to produce ‘a disembodied vision of nature’. The absence of any ‘traces of Indigenous bodies … was the key visual practice through which settler nature became possible as a concept and reproducible as an artistic project’. Initially this disembodiment was achieved simply by reframing scenes where Indigenous people were still present. But from the 1870s onwards the visual alienation of Country from its original inhabitants took the form of creating a new genre of ‘ethno-photography’ in which First Nations men and women were depicted either in the studio or in settler-assigned enclaves far removed from their homelands. Their disappearance from the ‘empty’ wilderness landscapes these photographers so lovingly pictured both anticipated and supported the ‘dying race’ narrative that took hold in some settler circles in the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

According to Hore, ‘Settler Romanticism’ was the aesthetic mode most favoured by these cameramen, at least when they were photographing the stunning highlands of California, Tasmania, and Aotearoa New Zealand. Like both the early English Romantic landscapists and later painters such as Albert Bierstadt and W.C. Piguenit, they were drawn to alpine environments and ancient monuments where the Sublime could still coexist with the relentless advance of imperial conquest and colonial modernity. By contrast, the settler-transformed lowlands ‘were captured and reproduced according to the stable conventions of pictorialist photography, which shaped a mode of representation that imagined the land as ripe for settlement’.

These settler visions of nature (and modernity) were in turn readily commodified and proudly displayed both locally and globally at a succession of international exhibitions. Whether in Melbourne, Hobart, and Dunedin, or in London, Paris, and Chicago, settler landscape photographs – alongside elaborate exhibits of colonial commodities and Indigenous artefacts – were potent advertisements for the achievements and prospects of these settler colonial societies. Indeed, in Hore’s view, ‘landscape photography turned out to be a perfect medium through which settlers could express both their advancement in the arts of civilization and demonstrate their control over territory and Indigenous people’.

As this incomplete summary of Hore’s argument suggests, the author has drawn on an impressive variety of disciplines, archives, and theoretical frameworks to craft a significant contribution to our understanding of the cultural dynamics of settler colonialism. (I haven’t even touched on his discussion of the origins of ‘settler nativity’.) That he has managed to transform his PhD thesis into such a coherent and comprehensible account is equally impressive. My only caveat is that Hore makes no attempt to relate the work of his landscape photographers to the other media and genres that constituted the Pacific Rim’s settler colonial visual cultures. For example, while he makes great play with how the reproducibility of their photographs made them so influential, he neglects the impact of the even more widely viewed wood-engraved images of the illustrated press, including those that depicted the ongoing presence of Indigenous peoples in settler cities as well as in the bush. Nor does Hore compare his subjects’ iconography with that of other late nineteenth-century artists, including the Australian Impressionists. This was a missed opportunity because, like the photographers, so many of their pictures could also be read as a series of white native title claims.

Seen in that light, Hore is right to see Visions of Nature as a contribution to the truth-telling called for by the Uluru Statement from the Heart, including his exposure of the claims to settler territoriality still embedded in Australia’s politics and culture. Indigenous artists have already shown the way forward with their own Dreaming landscapes’ evocation of Country. One day we may make real progress by replacing ‘Advance Australia Fair’ – that enduring hymn to settler colonialism – with an Indigenous version of ‘This Land Is Our Land’.

Comments powered by CComment