- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: A new accord: Restoring good relations between government and universities

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A new accord

- Article Subtitle: Restoring good relations between government and universities

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia’s new Commonwealth government has pledged to initiate a ‘universities accord’ and build consensus on higher education policy questions. This follows a period of torrid relations between universities and the government where constructive dialogue was patchy at best. We may have heard little from Labor about universities over the course of the past nine years, but its ‘universities accord’ election pledge at least recognises that, for the good of Australia and its people, it’s time to reopen constructive channels of communication.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

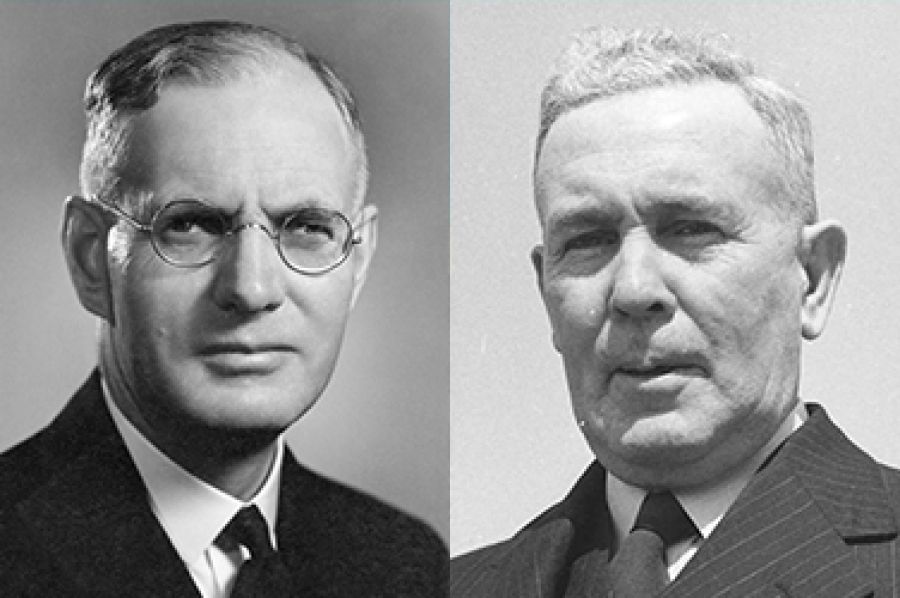

- Article Hero Image Caption: Former prime ministers of Australia, John Curtin and Ben Chifley (photographs via Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Former prime ministers of Australia, John Curtin and Ben Chifley (photographs via Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): 'A new accord: Restoring good relations between government and universities' by Julia Horne

In 1942, Prime Minister John Curtin and Treasurer Ben Chifley recognised the important role of higher education in Australia’s economic and social well-being. Fully aware that education was a state responsibility enshrined in the constitution, they looked to ways to support universities without upsetting the states. They utilised the experience of university professors who were seconded to the government to assist with wartime planning, and surprised vice-chancellors with the boldness of their ideas. They established an interdepartmental committee to investigate the issue of supporting needy students at university. In November 1942, Curtin announced an innovative plan to create a Universities Commission to formalise conversations with government. It grew out of vice-chancellors’ calls for a policy-making body that would liaise with universities and advise government on policy detail. It is a genesis story, the moment when the Commonwealth government began regular dialogues with universities about their place in national consciousness and in Australia’s prosperity.

The Universities Commission convened just a month after Curtin’s announcement, the speed due to the urgency of the new war-front in the Pacific. The idea of a ‘commission’ arose from a desperate need for Canberra to have constructive conversations with universities in this time of crisis. Part of the brief was to mobilise expertise to help win the war.

The universities had originally argued for an independent advisory body with its own secretariat. But Curtin decided that wartime conditions required closer oversight. While the Commission would be under the administrative control of Canberra, it was to be staffed by four senior men with relevant experience, three of whom had combined expertise in universities, adult education and schools, and the fourth, a member of parliament. Chaired by Richard Mills, professor and dean of economics at the University of Sydney, the mission was to incorporate universities into the Commission’s policy-making and advisory role to government.

Mills was at pains to reassure universities they were not under threat of government control. At the beginning of the five-day conference with university registrars in 1943, Mills began with a conciliatory statement about the independence of universities and the desire for constructive dialogue. ‘This Conference is not in a position to determine University policy,’ he explained to the assembled university registrars. ‘True, our discussions must, if they are to be real, spend all the time on such policy; but ... when we touch on policy we are not trying to decide University policy.’

Out of terrible wartime necessity came virtue. The Commission became a hub of activity organising ‘conferences’ with senior university representatives. These were formal meetings over a series of days with long agendas intended to determine broad policy directions and to resolve practical issues. When the Commission worked with university registrars, they rolled up their sleeves to discuss practical ways in which they could achieve policy goals. At one point, the Commission decided it needed meaningful statistics to inform new directions, and the registrars settled down for several days to establish what was possible. When they returned to their universities, they established new statistical processes which still provide extraordinary insight into the operations of mid-twentieth century universities.

At one conference, vice-chancellors complained about academic staff shortages due to war enlistment. Mills replied, ‘Give us the names and we will alert Dr Coombs so we can re-lease them immediately.’ At another, Mills was interrogated by vice-chancellors on the government’s decision to restrict recipients of Commonwealth research funding to the sciences and technology. Mills, an economist, quickly responded to say the remit included social sciences. But, challenged one vice-chancellor, what about modern history? Yes, said Mills, that might be possible.

In a matter of only seven years, the Commonwealth, along with universities, brought significant policy changes to higher education in Australia. These changes included a university scheme for the education of ex-servicemen and women that doubled total enrolments over this period and changed the student demographics. They also included a Commonwealth commitment to fund research, including the novel idea of building Australian research capacity through research students. The pace was fast and, arguably, successful because of the Commission’s collaborative will to translate government aspirations and university needs into workable policies. The Commission’s small band of hard-working men achieved what has seemed impossible in recent years: constructive dialogue and the forging of strong relations.

But what lessons for the newly elected Labor government in 2022? The overriding point is surely that higher education is a linchpin of Australia’s prosperity and social resilience in times of crisis. For Curtin and Chifley, the emphasis on education and training would provide opportunities to ex-servicemen and women (including in research) to bridge the gap between wartime service and civil society; and with enhanced credentials they would fill the ranks of an expanding workforce in a post-industrial world and contribute to economic productivity.

The second lesson is the power of constructive dialogue. The achievements of 1942 to 1949 were only possible because the Universities Commission provided a collegial space for debate between universities and the government and, when needed, a thriving, collaborative work space to nut out the details.

The new Labor government’s policy is currently short on detail. In two concise sentences it notes that ‘Labor will establish an Australian Universities Accord to drive lasting reform at our universities. The Accord will help deliver accessibility, affordability, quality, certainty, sustainability and prosperity to the higher education sector and the country.’

Our starting point is the simple phrase, ‘Australian Universities Accord’. Presumably, this means mutual agreement around key areas of policy. Identifying and understanding weaknesses in the current system will lead, it is to be hoped, to more complex and promising policy approaches to higher education.

There are many weaknesses, but three concern me most. First, inequity still pervades all levels of Australia’s educational systems. Educational disadvantage remains a major barrier to full university participation amongst young Australians. Universities are even today foreign places for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Despite some progress, the challenge remains to overturn this state of affairs. Not unrelated, there continues to be a lack of policy recognition that diversity at our universities, especially among university students, simultaneously increases Australia’s social, cultural, and economic well-being.

Then there is the funding issue. The public financing of the sector tends to be pursued exclusively in narrow fiscal and often perplexing terms without reference to how it improves social, economic, and educational impacts. Funding for research and major infrastructure, for example, is woefully short of the real costs; to fill the gap, universities resort to non-government sources. The result is that research, a ‘national priority’ for the greater good, is largely funded by international student fees, industry, and philanthropic support. It is useful, surely, to remember that one outcome of Curtin’s Universities Commission was to publicly fund university research, first for the war effort, and subsequently for prosperity in postwar Australia. Education was a major factor in Australia’s ‘long boom’ for the thirty years after the war.

Finally, let’s overturn the approach to higher education policy making and reform that in the past two decades has advanced the short-term rather than nurture more enduring gains. The approach has often been politically partisan and ideologically driven, rather than wide-ranging, consultative, inclusive, and imaginative.

How should the Universities Accord begin? Rather than establish a ‘small group of eminent Australians from across the political spectrum’, as recently proposed, let it begin with a Higher Education Summit. The Labor Party understands summits. They are proactive spaces where participants chart the future through consensus. They set agendas. They can be big and organised in ways that encourage diverse voices rather than being held hostage to destructive partisan politics. They celebrate constructive conversation and blue-sky thinking to inspire the next steps. They are an exciting beginning.

Who should be involved? I would like to see participants drawn from far and wide. There are the usual bodies such as the unions and the employers’ association, which provide important insight into the current industrial and fiscal state of universities. But for the summit to have a truly twenty-first century feel, we need to think more creatively about the invitation list.

Since social-democratic questions of ‘accessibility’ and ‘affordability’ are on Labor’s mind, let’s start with a broad representation of young people from all walks of life, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, those from other culturally diverse backgrounds, and women. Whether they are university students or not, their thoughts on higher education are surely essential to reform. Also important is representation from international students to understand this growing dimension of Australian university life.

We need perspectives from the disciplines themselves. There are five Australian Academies covering the humanities, science, the social sciences, health and medical sciences, and technology and engineering. The presence of representatives from all the Academies at a summit would provide a variety of insights into the importance of modern universities. Let’s use the brains of these men and women, their expertise and extensive higher education experience to help make Labor’s Universities Accord a reality.

And we need educationists with expertise in ‘closing the gap’ at schools. The most common mode of entry to university is still through an examination held in the final year of high school. But to take the next steps in broadening social access to higher education, we need to appreciate the nature of educational disadvantage, how its entrenchment at an early age becomes the major barrier to higher education later.

In The Boldest Experiment (2015), the Australian historian Stuart Macintyre told the following anecdote. In 1942, an ever-growing chorus of Australian voices argued the need for a national education plan. Charles Bean, the historian of World War I, put it bluntly: ‘It doesn’t matter much what else you do – educate and you solve the problem; fail to educate, and nothing else can save you.’

I hope the current government is as inspired about education as Curtin and Chifley were in 1942.

This commentary is generously supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment