Listen to this essay read by the author.

The dismissal of the Whitlam government by the governor-general, Sir John Kerr, on 11 November 1975 was one of the most tumultuous and controversial episodes in Australian political history. The government had been elected on 2 December 1972 and returned at the May 1974 double dissolution, with Whitlam becoming the first Labor leader to achieve successive electoral victories.

The prime minister was at Yarralumla at 1 pm on 11 November to sign the final paperwork for the half-Senate election that he was to call that day. Kerr had agreed just that morning on the wording of the announcement that Whitlam was to make that afternoon in the House of Representatives. That Kerr dismissed Whitlam at that moment and without warning only added to the legal and political furore at the time and ensured its continuing contestation ever since.

With such extraordinary provenance, at once fascinating and disturbing, it is hardly surprising that the rancour, division, and fierce debate that greeted Kerr’s actions have never ended. The dismissal raised fundamental legal and political questions about the relationships, responsibilities, and conventions of parliamentary democracy in a constitutional monarchy, and personal questions of propriety and ethics in high office. It is as irresistible, operatic, and compelling today as it was forty-five years ago.

In terms of the historiography, the last decade has been a sharp corrective to history, propelled by a series of archival revelations that have gradually and collectively recast our understanding of the dismissal and challenged even its most established historical facts. It is remarkable that even today, more than four decades later, critical documents about the dismissal remain secret, hidden from public view and from history. The ‘Palace letters’, correspondence between Queen Elizabeth, Sir Martin Charteris (her private secretary from 1972 to 1977), and Kerr relating to the dismissal are among Kerr’s papers held in the National Archives of Australia. They are embargoed ‘on the instruction of the Queen’ until at least 2027, after which their release requires the approval of both the governor-general’s official secretary and the monarch’s private secretary, giving the monarch an effectively indefinite veto over their release. We cannot see the letters until the queen or her successor, King Charles, says we can.

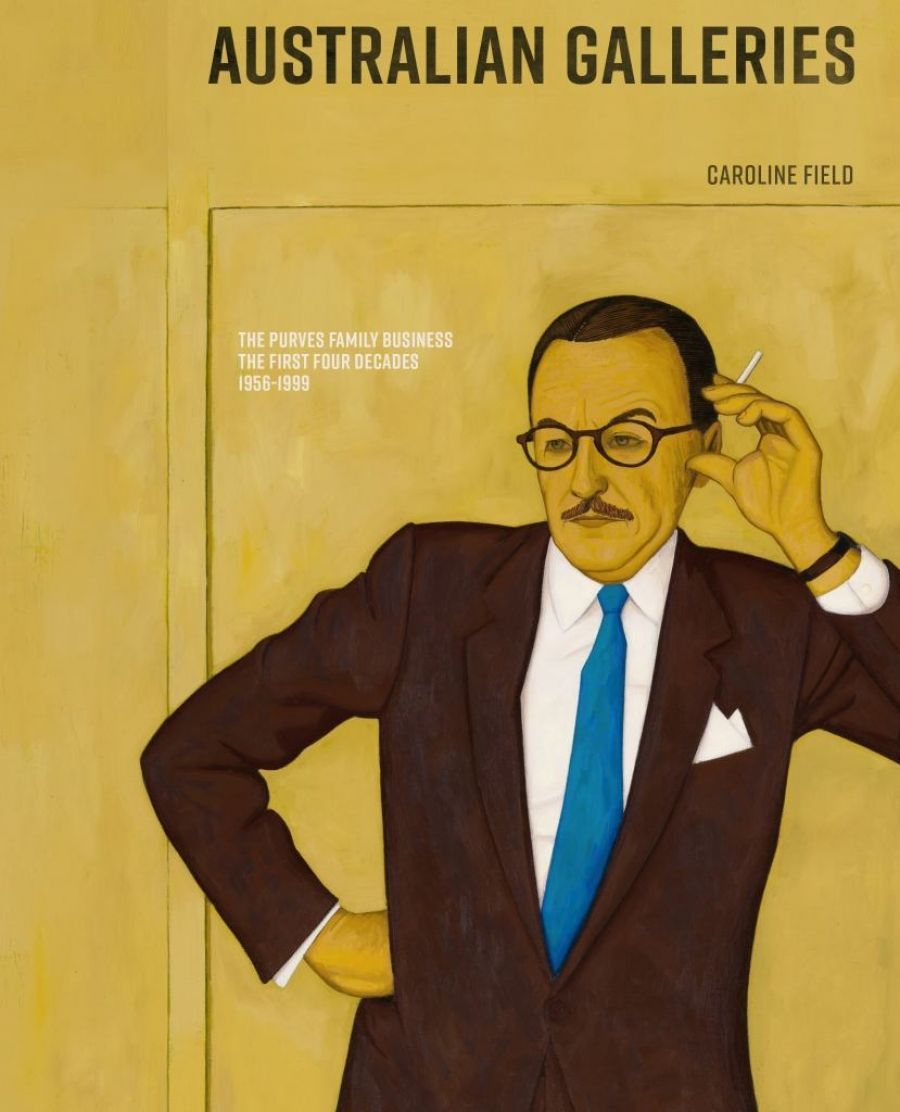

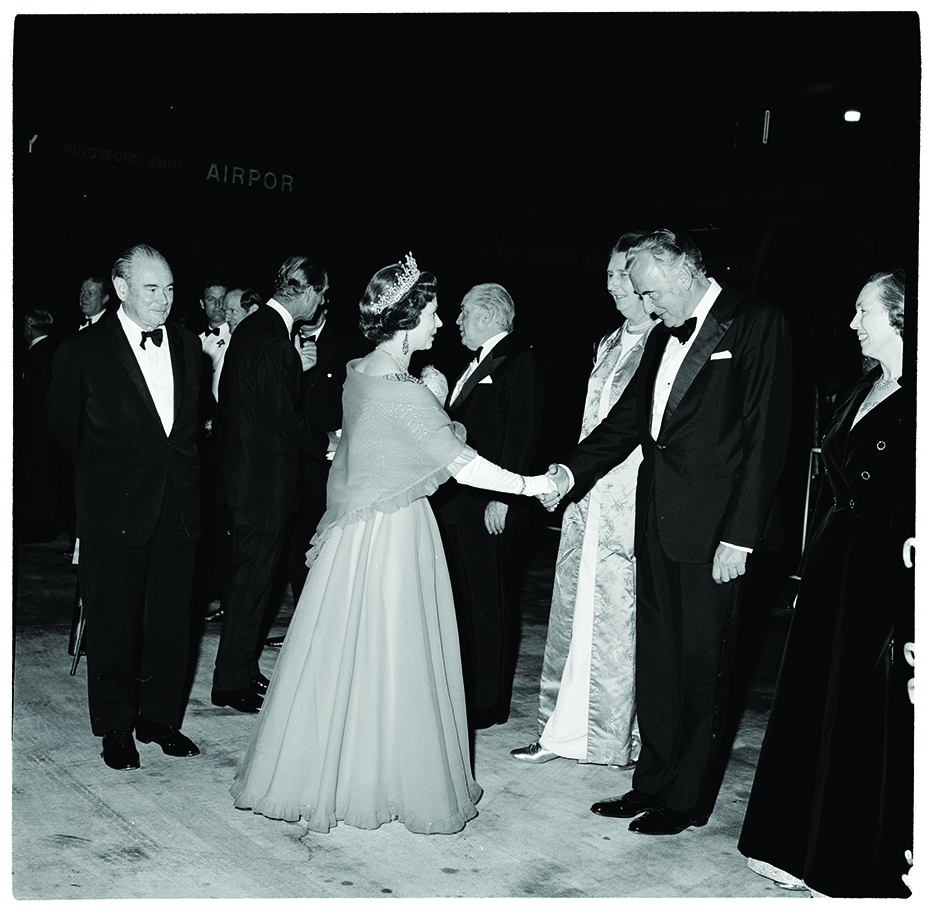

Queen Elizabeth II departing Australia at the Sydney airport farewelled by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam, 1973 (National Archives of Australia NAA A6180 2510733)

The importance of the Palace letters lies in the evolving history of the dismissal of which they are the last of the ‘unattainable archives’, without which the history will remain flawed and incomplete. In the continuing process of revelation and historical (re)construction that has reframed the history of the dismissal in recent years, Kerr’s papers in the National Archives have been of unparalleled significance. It was there that I discovered Kerr’s notes revealing the role of the then High Court Justice Sir Anthony Mason, who was Kerr’s secret confidant and ‘guide’ over several months before the dismissal, ‘fortifying me for the action I was to take’, as Kerr described it. Mason’s role extended to drafting a letter of dismissal for Kerr. As Paul Kelly has said, the only possible conclusion is that Mason ‘was implicated in the dismissal’. In its fracturing of what had become the central dismissal orthodoxy – that Kerr had acted alone, reaching ‘a lonely and agonising decision’, as the veteran journalist Alan Reid flamboyantly described it – this was the most significant of the dramatic revelations to come from Kerr’s papers in recent years.

A more profound breach of the separation of powers, not to mention personal probity, would be difficult to find, and yet Mason’s role had been kept secret for thirty-seven years, at his own insistence. In this Mason was not alone in seeking to hide his role in this troubling moment in history. The construction of a flawed, at times even false, history by those involved is one of the more disturbing aspects shown by the tumble of revelations in recent years.

One of the more dramatic, and frankly shocking, instances of calculated distortion was revealed in correspondence released by the Archives in 2019, eight years after I first requested it. These letters, between the queen’s private secretary and Kerr in 1978, after Kerr had left office, show the Palace overseeing the final version of Kerr’s autobiography, Matters for Judgment (1978), to ensure that there would be no mention of Kerr’s secret discussions with Charteris at the time of the dismissal. Kerr assured the Palace, ‘I did my very best of course to omit any reference to the exchanges between Martin Charteris and myself.’ This is history by carefully structured omission, a royally sanctioned whitewash of history. It shows Kerr to be as unreliable in print as he was in office.

Kerr’s ‘exchanges’ with Charteris at the time of the dismissal are documented elsewhere in his archives: in his 1980 journal in which he details discussions with Prince Charles and Charteris and cites some of his letters to and from the queen; and in a handwritten list of fourteen key ‘points on dismissal’, which includes ‘Charteris’ advice to me on dismissal’. The clear connection between the Palace and Kerr’s planning for the dismissal of the government is impossible to avoid since, according to Kerr, the queen’s private secretary had advised him on it.

That the ‘Palace letters’ are tremendously important historical documents is beyond dispute. They are a contemporaneous record of Kerr’s version of the circumstances of the dismissal, including the dismissal itself, and at the same time they constitute part of that history as it unfolded. Their release would fill one of the last remaining gaps in the historical record of the dismissal. The National Archives has denied access to the letters on the grounds that they are ‘personal’ communications and not ‘Commonwealth records’, and that, as a consequence, the open-access provisions of the Archives Act (1983), under which they would have been available for public release after thirty years, do not apply.

That correspondence between the monarch and the governor-general, two positions at the apex of a constitutional monarchy, could be seen as ‘personal’ is, on a common-sense reading, manifestly unsupportable. Kerr himself described them as ‘despatches’, as part of his ‘duty’ as governor-general, and they were deposited in the archives in 1978 by David Smith in his capacity as official secretary to the governor-general, after Kerr had left office, and not by Kerr himself. The Archives contends that as ‘personal’ records the letters are strictly governed by what it terms ‘Kerr’s instrument of deposit’ setting out the conditions of access to them: ‘When the Archives accepts such a [personal] collection, we undertake to adhere to arrangements agreed to with the depositor.’

The quandary here is that Kerr did not agree with and sought to change his ‘personal’ terms of access. It was no secret that he wanted his correspondence with the queen to be released, believing that it would vindicate his version of events surrounding the dismissal. Adding to the confusion is that the original Instrument of Deposit attached to the Palace letters by Smith was later changed ‘on the Queen’s instructions’ after Kerr’s death. (I’m not sure how that works for Kerr’s apparently ‘personal’ conditions of access.) It was this change that gave the monarch’s private secretary a lasting final veto. All of which is extremely difficult to reconcile with the concept of the letters as Kerr’s ‘personal’ property.

The Archives Act (1983) makes no such explicit exclusion of the governor-general’s records in general or the vice-regal correspondence with the monarch in particular from its provisions. The designation of the letters as ‘personal’ means that not only are they not subject to the open-access provisions of the Act, but there is also no means of administrative review of the decision to deny access to them. The label ‘personal’ has set an impenetrable legal catch-22, denying both access and review through that single powerful word ‘personal’.

The only avenue to challenge the denial of access to personal records is through a Federal Court action. In September 2016, I launched legal action against the National Archives of Australia in the Federal Court, seeking the release of the ‘Palace letters’. The case centres on the critical question of whether the letters are ‘personal’ or Commonwealth records, which is defined in the Archives Act in terms of property. The core question is: are these letters between the queen and the governor-general the property of the Commonwealth or the property of Sir John Kerr and his family?

The case has been supported by a crowdfunding campaign, Release the Palace Letters, with a legal team working on a pro bono basis led by Antony Whitlam QC at trial, Bret Walker SC at the Appeal and the High Court, with Tom Brennan throughout and instructing solicitors Corrs Chambers Westgarth. After nearly four years, the case has been through the Federal Court and the full Federal Court on appeal. In February 2020 all seven judges of the High Court of Australia heard the case on appeal.

In March 2018 the Federal Court acknowledged the ‘clear public interest’ in the Palace letters, which address ‘topics relating to the official duties and responsibilities of the Governor-General’, relating ‘to one of the most controversial and tumultuous events in the modern history of the nation’. Nevertheless, the Court found that the letters are ‘personal’ and not Commonwealth records, effectively continuing the queen’s embargo over them. In our appeal against that decision, the majority of the full Federal Court in a split 2:1 decision again ruled that the Palace letters are ‘personal’ records. In his strong dissenting judgment, Justice Flick found that it would be ‘difficult to conceive of documents which are more clearly “Commonwealth records” and documents which are not “personal ” property’. The Palace letters, Justice Flick stated, concern ‘“political happenings” going to the very core of the democratic processes of this country’.

Questions on notice in parliament in 2019 from Julian Hill, the Labor member for Bruce, have revealed that prior to the High Court appeal the National Archives had spent close to $700,000 contesting the case. This expenditure comes at a time when the Archives has faced resource pressures, diminishing budgets, and the loss of twenty-five per cent of its staff in the last decade, economies that the director-general of the Archives, David Fricker, has acknowledged have impacted severely on service delivery. The federal attorney-general, Christian Porter, intervened on behalf of the Archives, and the attorney-general’s department has contributed twenty-five per cent of Archives’ costs at the High Court appeal. These federal government bodies have now spent more than $800,000 fighting this crowdfunded case, reinforcing the formidable institutional imbalance faced in taking this action.

The Tune Review into the Archives was completed last year with the common theme recurring in submissions from historians and researchers being the inordinate and unacceptable delays in dealing with requests for access to its records. I am by no means alone in having twenty requests for access, requests that the Archives is statutorily required to deal with within ninety days, still pending after nine years. The Archives appears a broken institution, paralysed by delay, hamstrung by resource pressures, and indifferent to its core function ‘to connect Australians to the nation’s memory, their identity and history’.

The case has already revealed important details about the nature of the letters, and about the curiously arcane relationship between the Palace and the governor-general. Kerr wrote frequently, at times writing several letters in a single day. Central to their correspondence was the prospect of Kerr’s possible removal of the Whitlam government, which Kerr states in his papers he had first raised with Prince Charles in September 1975. Kerr’s letters included other material, commentaries about the political situation and about the governor-general’s powers, and copies of other people’s letters to Kerr.

These enclosures are particularly important in understanding the influences and authorities Kerr was relying on as he considered the dismissal of the government. They would also tell us just what version of the highly polarised political situation Kerr was conveying to the queen. Did he reveal to her, for instance, his negotiations with Sir Anthony Mason, his discussions with Sir Garfield Barwick, or his secret communications with the leader of the opposition, Malcolm Fraser? Most importantly, did Kerr inform the queen of Whitlam’s decision to call the half-Senate election? What is not in the letters will be as important as what is in them.

The Palace letters case has provided a rare opportunity to challenge in open court an entrenched presumption (even in our own National Archives) of royal secrecy, a residual ‘colonial relic’, as Whitlam described such lingering imperial pretensions. The ‘personal’ status of the letters reflects the easy means by which royal communications have been kept from the public both here and in Britain in order to protect the vaunted ‘political neutrality’ of the Crown. This simply confuses secrecy with neutrality and keeps hidden examples of royal political intervention under the guise of ‘personal’ communications.

The powerful archival descriptor ‘personal’ appears at best a misnomer and at worst a sophistry which maintains a veil of secrecy over the queen’s communications with the governor-general at a time of great political controversy, in which the question of the prior knowledge of the queen is singularly important. As Professor Anne Twomey has said, ‘If neutrality can only be maintained by secrecy, this implies that it does not, in fact, exist.’

It is entirely fitting that these fundamental questions of access and control over our archival records, of the functions and powers of the governor-general, and of our national autonomy – questions that go, as Justice Flick said, ‘to the very core of the democratic processes of this country’ – will now be determined by Australia’s highest court, and not the queen.