- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

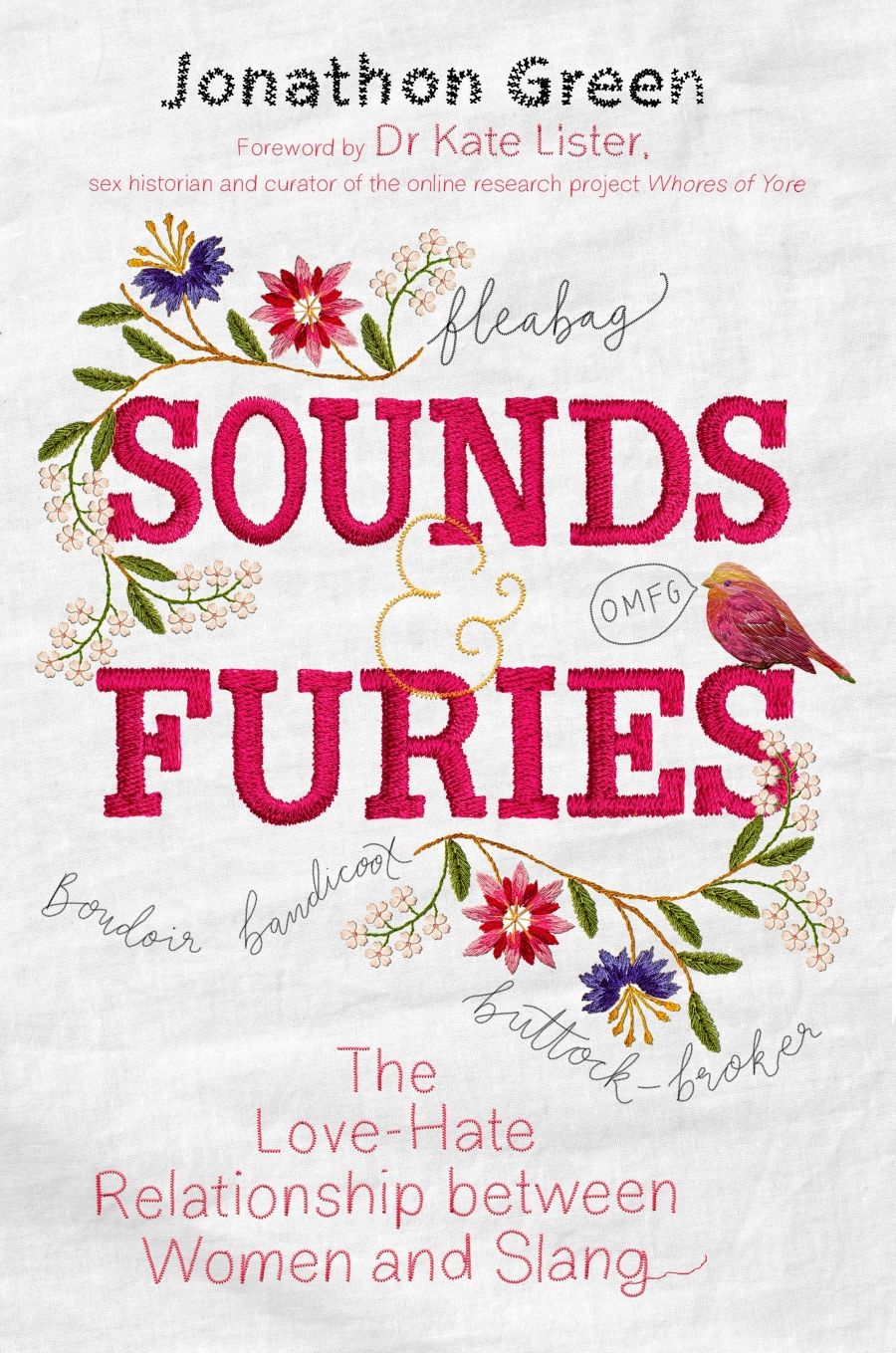

- Book 1 Title: Sounds and Furies

- Book 1 Subtitle: The love–hate relationship between women and slang

- Book 1 Biblio: Robinson, $29.99 pb, 564 pp

Green himself acknowledges the problem – well, a couple of problems. First, there is the issue of evidence. We have limited examples of slang as created by women, except in the last century or so. Even when women have been writers and authors, they are constrained by a stereotype that slang is ‘unfeminine’ and the domain of men, and thus often refrain from using much slang in their writing. Especially before the twentieth century, works that purport to be by women and that contain lots of slang are of questionable provenance; a number of works supposedly by women were more likely written by men (Green calls these ‘ventriloquised’).

Second, the slang lexicon all too often objectifies women: they are typically seen only as sexual objects or hags. We risk struggling to find any kind of authentic voice that reflects women’s experiences of the world. Reading this book, with its copious and dispiriting lists of words to describe women, threatens to illustrate this: cat, chick, stunner, doll, sheila, cookie, dog, skank, pig, skeezer, slag, floozie, bimbo, chippie … The list goes on.

So where do we find the authentic voices of women in the world of slang? Green offers us a few ways into this. Domains that can be seen as belonging to women give us some slang: for example, the vocabulary of pregnancy (up the spout, have a joey in the pouch), menstruation (Rita red pants, Auntie Flo), and abortion (bring it away, crack an egg). Women sex workers generate and have generated across time a large slang vocabulary (about them, if not by them): intercourse is fancy work, the brothel the banging shop, and the customer is a trick.

We also meet some colourful characters along the way. The notorious Moll King, immortalised in a posthumous biography published in 1747, made much use of the flash language of the criminal underworld of eighteenth-century London. Here is a taste of her dialogue: ‘There’s a Grunter’s Gig, is a Si-Buxom; two Cat’s Heads, a Win; a Double Gage of Rum Slobber, is Thrums; and a Quartern of Max, is three Megs.’ Moll is in conversation with a customer who is asking how much he should pay for his dinner: si-buxoms, wins, thrums, and megs are all slang terms for various denominations of coin. Nell Kimball’s account of her life as an ‘American madam’ was published in 1970 but was written in 1930. Her book contains some 260 slang terms, with graphic sexual slang as befitting her occupation. The vagina is the quiff, muff, snatch, split, crack, and cunt; the ultra-virile man is known as a stud or a cocksman, and the masturbator a duff flogger.

The 1920s ‘flapper’ (preceded by the ‘fast girl’) was well known for her distinctive vocabulary, compiled into ‘The Flapper Dictionary’ that first appeared in 1922. Anyone aged over thirty was a green apple or old fop, an older woman was a covered wagon, and a lover’s tiff was described as a flat shoe. Teenage girls through the twentieth and twenty-first century have continued to cultivate a unique slang as well as to demonstrate that young girls make use of slang as much as anyone. Kathy Lette and Gabrielle Carey’s Puberty Blues (1979) captures the slang of young girls in the late 1970s and contributes to our record of Australian English: packing shit, pash, and slack-arsed are the kinds of terms immortalised in its pages.

The internet has also served to make women’s slang more visible. Green makes much use of the online forum Mumsnet to track various slang terms. This forum is particularly fond of the acronym, so we have PITA ‘pain in the arse’, NAK ‘nursing at keyboard’, and the initialism AIBU ‘am I being unreasonable?’ among many others. And while lesbian slang has historically proven difficult to trace, there does appear to be vocabulary that circulates to some extent within online communities, such as celebudyke for a lesbian famous for doing nothing, hetty for heterosexual, and luppies for lesbian yuppies.

Like all collections of slang, it is difficult to know how widely used many of the words really are. There is also something depressing about the way in which women’s relationship to slang has been overwhelmingly defined by women’s biology and especially their status as sexual objects. While women’s agency in all this is certainly discernible in Green’s study, the connection to the larger structures of power that have historically circumscribed women’s lives, and sought to define their identity, could perhaps have been further explored.

Where do we go from here in studying the story of women and their troubled relationship with slang? Green calls for more people to take up the challenge of uncovering other aspects of this story. It would be interesting to see in particular what a woman’s eye might bring to it.

Comments powered by CComment