- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Truganini: Journey through the apocalypse follows the life of the strong Nuenonne woman who lived through the dramatic upheavals of invasion and dispossession and became known around the world as the so-called ‘last Tasmanian’. But the figure at the heart of this book is George Augustus Robinson, the self-styled missionary and chronicler who was charged with ‘conciliating’ with the Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples. It is primarily through his journals that historians are able to glimpse and piece together the world fractured by European arrival.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

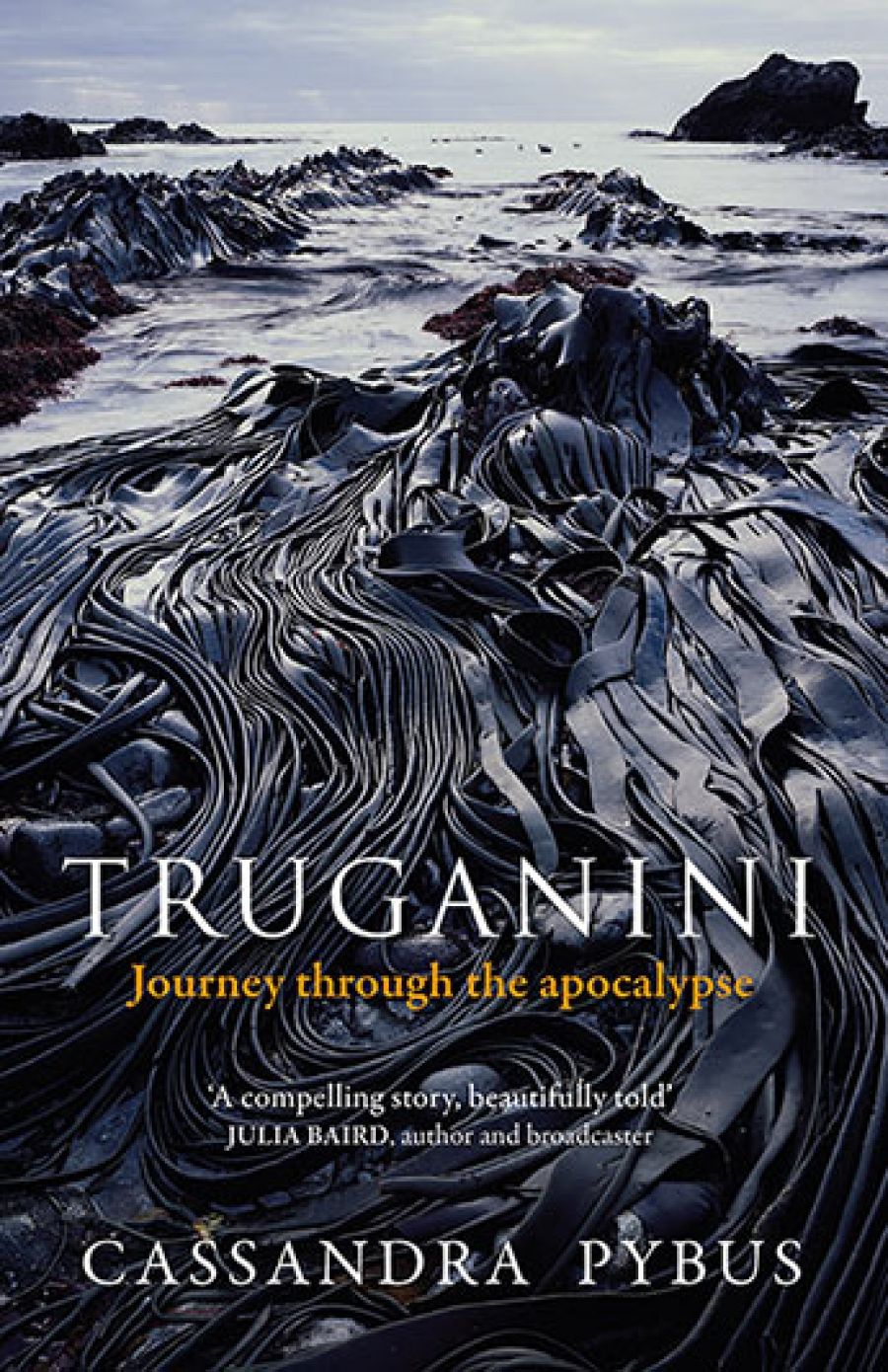

- Book 1 Title: Truganini

- Book 1 Subtitle: Journey through the apocalypse

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 336 pp

Although the book is framed as a biography, Truganini remains elusive in its pages, always seen through the eyes of others, always at the edge of their vision. Often several pages pass between mentions of her name. What Pybus offers instead is a vivid retelling of Robinson’s journals, and a narrative exploration of Truganini’s turbulent times. Pybus sets out to ‘liberate’ the Aboriginal peoples trapped within the colonial records. As a descendant of a family that usurped Nuenonne Country, she deems her task to be ‘no less than a moral necessity – these are people whose lives were extinguished to make way for mine’.

Truganini, Billy Lanne, and Bessy Clark (photograph supplied)

Truganini, Billy Lanne, and Bessy Clark (photograph supplied)

There is a moment in the book when Truganini, Pagerly, and Plorenernoopner are travelling with two convicts along a river and their raft is pulled into a dangerous current. Pagerly and Plorenernoopner lose hold, while Truganini, who was a famously strong swimmer, clings to the logs, urging the convicts to abandon the makeshift vessel. They refuse, she loses her grip, and the raft splinters on the sandbar at the rivermouth; the convicts’ bodies are swept out to sea. This story is relayed in a paragraph, and Pybus offers two sentences on what the incident must have meant for Truganini: ‘Truganini was distressed to witness the final moments of these men, who had accompanied her on several missions and had always been kind to her. She was deeply regretful that she had lost hold.’

I repeat this story as it is characteristic of the drama of the book and the pace of the narrative. But how do we know of this incident? Indeed, how do we know what Truganini thought and felt? As Pybus acknowledges in her introduction, ‘There is no way I can know what she thought or how she felt. I cannot imagine what it was like to be her, or to feel what she experienced. It would be inappropriate to attempt it.’ And yet, this is a book that does attempt to imagine Truganini’s life and experience, and it strains against those limitations.

As to how we know about the incident with the raft, the reader simply has to trust Pybus, who is opaque about her sources. There are no footnotes and no engagement with secondary literature. The immense historiography that surrounds Truganini is either ignored or taken to be assumed knowledge. The only oral history Pybus appears to have consulted is that of her own family, whose ancestors told the story of an old Aboriginal woman who wandered across their farm on Bruny Island in the 1850s and 1860s.

In many ways, Truganini can and should be seen as a companion piece to Pybus’s first book, Community of Thieves (1991), which follows the same events, features the same characters (even the same plates), and is also framed through the Pybus family connection to the lands of the Nuenonne. But these are very different books. Community of Thieves questions silences and fills them with inference, speculation, and conjecture. The text is littered with uncertainty – ‘I am not sure’, ‘I cannot tell’, ‘It seems’ – and it is all the richer for it. When Robinson turns his back on Truganini in 1842 and dispatches her back to the desolate settlement on Flinders Island, Pybus intuits it as a betrayal: ‘How can I know what effect this final betrayal had on Truganini..? I do not know. I cannot know. I have no evidence that they were aware of Robinson’s rejection. But they knew.’

The book opens with an idyllic vision of the pre-invasion world of the Nuenonne: a ‘healthy, happy’ people who live a harmonious existence of ‘timeless reassurances’. Truganini is born in 1812 into a very different world. She experiences the violence, trauma, and mayhem of dispossession. At the age of four her mother is violently killed on a beach off the southern end of Bruny Island. Ten years later, her sisters, Lowhenune and Magerleede, are abducted by the sealer John Baker. She never sees them again. Her fiancé is mutilated by sawyers. In April 1829 she meets Robinson, who is drawn to her obvious intelligence, grasp of English, and striking looks. Their lives are deeply entwined for the next thirteen years as she joins him on his so-called Friendly Mission across Van Diemen’s Land to the desolate offshore processing centre on Flinders Island and then on to Port Phillip. They were never sexual partners, as other biographers have suggested. The role Robinson cast for himself, Pybus argues, ‘was even more intimate and binding than that of a lover: he was the good father who would protect and save her’.

In Port Phillip, ‘the good father’ loses interest in Truganini; her name drops out of his journals. ‘Effectively, he had closed the book on her.’ In 1842 she returns to Flinders Island, where so many of her compatriots died, and then in 1847 moves on to the Oyster Cove Aboriginal station, where she lived until it closed in 1871. She died in Hobart in 1876.

Truganini, of course, is known as much for her afterlife as for her life. She has been the subject of myth-making, fantasy, and fabrication; her life has been interrogated and dramatised in many novels, plays, films, poems, and biographies, as well as volumes of fine-grained historical research. Pybus has chosen not to engage with these myriad accounts of Truganini’s life, ‘such as can be found on any Google search’. Rather, she is determined to use the ‘original eyewitness accounts’ to return Truganini’s life to the centre of her story: to explore ‘how she lived, not simply that she died’. ‘I set myself the rule because I am sick of all the myth-making ... I wanted the contemporaneous accounts.’ While there is something beautiful about this rationale, the decision not to engage with the historical context, not to confront the myth-making, has unintended consequences.

In searching for ‘the woman behind the myth’, Pybus does not unpack how and why Truganini has become famous: the countless ways in which she has been sensationalised, sexualised, and slandered; how her story has been mobilised to reinforce racial hierarchies and narratives of extinction, extermination, and inevitable demise; and how her life has been reclaimed by the Tasmanian Aboriginal community today as a symbol of rights, identity, ownership, and survival.

Instead, Pybus replaces the myth with History. She writes vividly of ‘the dispossession and destruction of the original people of Tasmania’, describing invasion as their ‘apocalypse’ and their story of struggle as a ‘regrettable tragedy’. The final section of the book is even titled ‘The Way the World Ends: 1842–1876’. It is powerful, seductive language. And yet, the world didn’t end for Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples. It was transformed. This narrative arc lies at the heart of Pybus’s earlier work – indeed Community of Thieves tackles extinction narratives head-on – but in Truganini this knowledge is assumed. But how does this story of survival change the moral legacy of Truganini? And can one truly understand her without engaging with it?

These are serious questions, because while its use as a scholarly source is limited, Truganini will reach many readers. It is written with literary flair, compassion, and insight, particularly into the complex character of George Augustus Robinson and his peculiar cognitive dissonance. And it is beautifully produced, with luminous colour plates and an appendix of accessible potted biographies.

The striking cover features a photo by Peter Dombrovskis of giant kelp strewn over the rocks of Macquarie Island, its thick black tentacles glistening in the half-light. It powerfully captures the dark mood of the book, summoning an image of the waves of invaders that have crashed against Tasmanian shores, sweeping away much that was there before. But not all. What remains is a story that is eerie, at times beautiful, but most of all monstrous.

Comments powered by CComment