- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

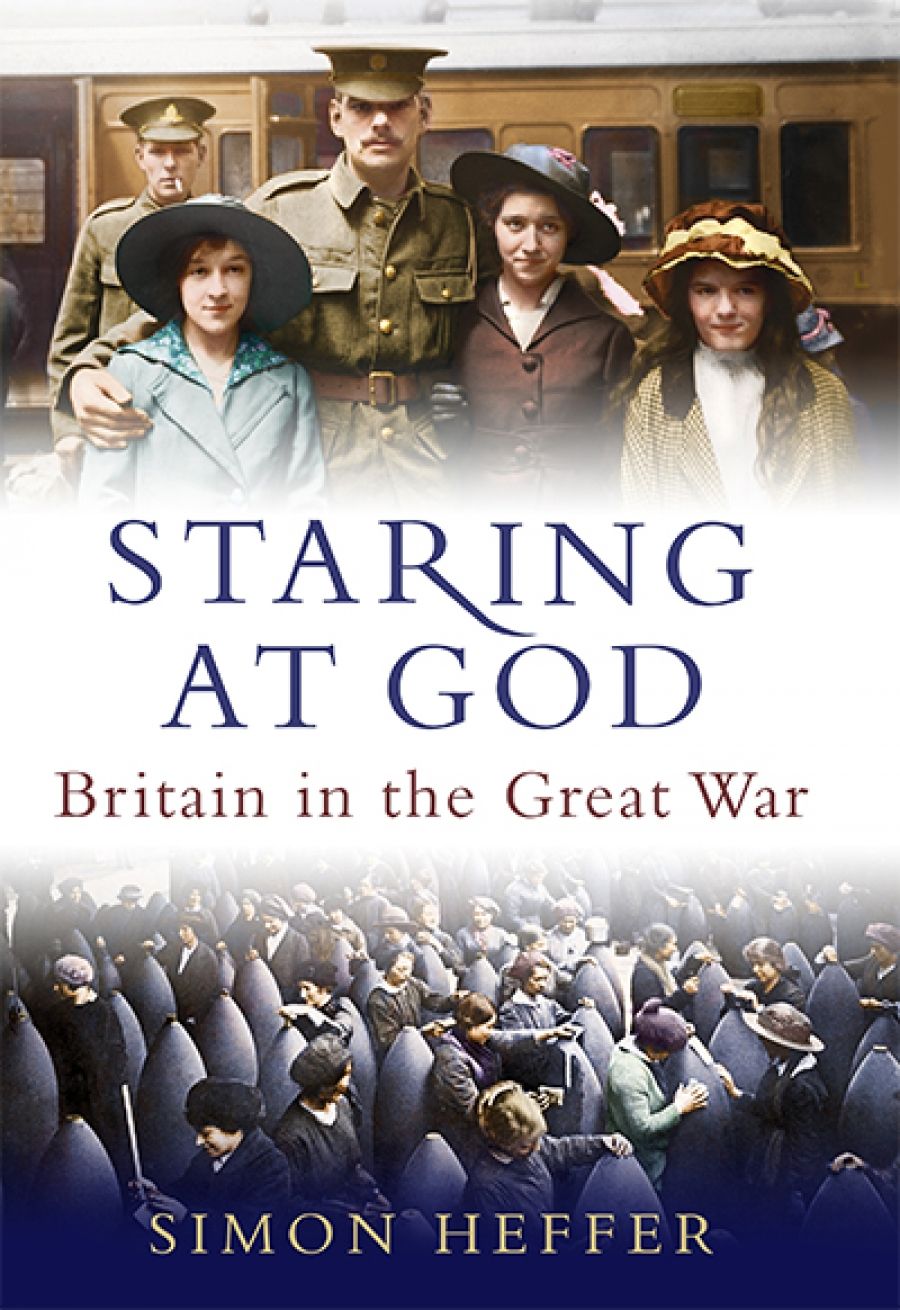

It seems hard to imagine that we need more books on World War I after the tsunami of publications released during the recent centenary. Yet, here we have a blockbuster, a 926-page tome, Staring at God, by Simon Heffer, a British journalist turned historian in the tradition of Alistair Horne and Max Hastings.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Book 1 Title: Staring at God

- Book 1 Subtitle: Britain in the Great War

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin Random House, $59.99 hb, 926 pp

Heffer’s focus is thus on high-level British politics, the men who directed the nation’s strategy, its mobilisation of manpower, and its vast industrial war effort. The actual battles, which caused such revolutionary changes in Britain and which fuelled corrosive disputes between British political and military leaders, are left in the wings. This, Heffer explains, is because so much has been written about them elsewhere, as indeed it has.

Many pages are devoted to the struggles for power between politicians and to the role of the Northcliffe press in these manoeuvres. Key dramatis personae are Herbert Asquith (prime minister, 1908–16), Andrew Bonar Law (leading conservative and later prime minister), the press baron Viscount Northcliffe, and Asquith’s successor, David Lloyd George, a man who, for all his charisma and extraordinary achievements in mobilising the British economy, does not seem to win Heffer’s approval.

This all makes for interesting reading, given that these politicians left sources that Australian historians of the war must envy. Asquith was besotted with a young woman, Venetia Stanley, to whom he wrote obsessively, even during cabinet meetings and sessions of the Council of War. With astonishing indiscretion, he confided not just his political woes but also sensitive information, including troop movements. Asquith’s long-suffering wife, Margot, and Lloyd George’s mistress (later wife), Frances Stevenson, also left eminently quotable material. All of this, and more, Heffer mines to great effect, although, for this Australian reader, the detail about the intrigues of the British political class was excessive. Do we really need to follow Asquith’s final fall from power in late 1916 for about thirty pages?

Heffer certainly addresses the wider impact of the war: the introduction of conscription; the rapid growth of the munitions industry; the impact of Zeppelin raids on civilians; the use of the Defence of the Realm Act for purposes of control, including censorship; propaganda; the cultural responses to the war; food rationing; industrial unrest; and of course, the Easter uprising and its implications. Yet, in the end, the voices that come through most strongly are those of British leaders, not the people they led. No oral history sources seem to have been used.

What does this book, which assumes a knowledge of British history, offer Australian readers? Most obviously, it throws into relief Australia’s own experience of the war. Australians were profoundly traumatised by the 62,000 deaths, possibly the highest mortality rate proportionately of any of the British Empire’s armies. The debates about conscription and the rising cost of living also tore Australian communities apart, leaving a toxic political legacy. Yet in Australia there was nothing comparable to the structural changes in the economy and the workforce that Heffer documents vividly in Britain. While women formed 46.7 per cent of the British munitions workforce by the end of the war, in Australia women were largely consigned to traditional gendered roles: nursing, knitting, fundraising, and packing parcels of comforts for their soldiers.

This book also reminds us of how remote Australians were from the physical dangers of war. Not for them the Zeppelin raids which in one day alone in 1917 killed ninety-five people in Folkestone. Nor did Australians face dire food shortages, however troubling the inflation in commodity prices was during the war. When compared with Britain, then, Australia did not really experience ‘total war’, though this term is arguably not as relevant to Britain in World War I as it was in World War II.

Other points of interest are Heffer’s discussion of the financing of the war effort. In the interwar years, Australians complained about the cost of servicing of the war debt that they had incurred in funding the operations of the Australian Imperial Force. But Britain, too, incurred massive debts by borrowing from the real ‘winner’ of the war, the United States. At the time of armistice, Britain’s national debt was fourteen times the level of 1914. Britain owed its overseas creditors £1,365 million, and was itself owed £1,741 million, most of which it had borrowed from the United States and then lent to allies. One such ally was Russia, which repudiated its debt with the coming of the Bolshevik revolution. Even had the British Treasury wanted to – and not all of its officials did – it could not have been more generous regarding Australia’s debt.

Australian readers might also appreciate the detailed account of the Dardanelles campaign from the British perspective. Winston Churchill has long been pilloried by Australians as the ‘bungler of the Dardanelles’, and Heffer reveals the deep, almost visceral distrust of Churchill among the British political élite. From the vantage point of 1915, it seems impossible to imagine his iconic leadership of 1940. Asquith told Venetia Stanley: ‘I regard [Churchill’s] future with many misgivings. He will never get to the top in English politics ... to speak with the tongues of men & angels, and to spend to laborious days & nights in administration, is no good, if a man does not inspire trust.’

Interestingly, too, Australians scarcely feature in Heffer’s account of Gallipoli. But then, how often do Australians acknowledge that the British and Irish fought at Gallipoli; let alone that they lost more than 21,000 dead as opposed to Australia’s 8,000? For all the transnational commemorations of recent years, much of World War I history and memory remains incurably national.

Comments powered by CComment