- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: United States

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rising to the lectern amid a tightly packed crowd in the Cambridge Union’s debating hall, James Baldwin began quietly and slowly to speak. ‘I find myself, not for the first time, in the position of a kind of Jeremiah.’ It was February 1965, and Baldwin was in the United Kingdom to promote his third novel, Another Country (1962). Baldwin’s British publicist had asked the Union if they would host the author. Peter Fullerton, the Union’s president, was quick to seize this opportunity, on one condition: that Baldwin participate in a debate.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

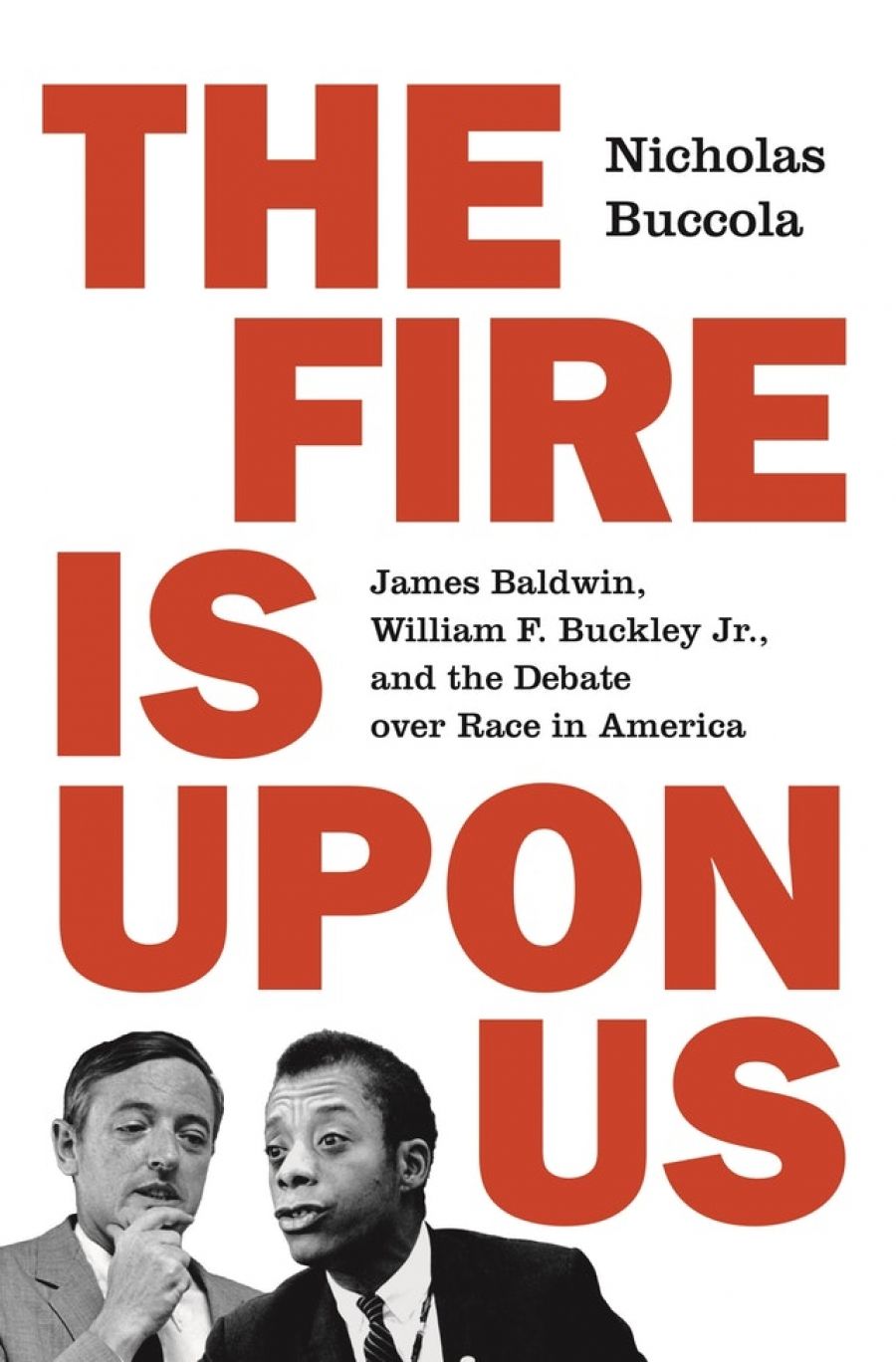

- Book 1 Title: The Fire Is Upon Us

- Book 1 Subtitle: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the debate over race in America

- Book 1 Biblio: Princeton University Press (Footprint), $79.99 hb, 482 pp

Baldwin’s opponent that day was William F. Buckley Jr. One might have supposed that Buckley would prevail in such a debate. Not only was Buckley an established and ruthless debater, but by February 1965 he was the most prominent American conservative intellectual and perhaps the most famous representative of the nascent modern conservative movement, second only to Barry Goldwater. Buckley – a Yale graduate who was raised on a sprawling Connecticut estate, educated by countless private tutors, and spoke with a distinctive if idiosyncratic transatlantic accent – should have swayed the similarly privileged Cambridge undergraduates. Yet, Buckley’s attacks on Baldwin and his attempts to defend not only the idea of the American dream but, more broadly, a conception of Western and Christian civilisation under threat, fell utterly flat in the Union hall. Baldwin easily won the debate. Buckley would see this defeat as proof of both British anti-Americanism and the intellectual hypocrisy of secular liberal élites.

James Baldwin taken in Hyde Park London, 1969 (photograph by Allan Warren/Wikimedia Commons)

James Baldwin taken in Hyde Park London, 1969 (photograph by Allan Warren/Wikimedia Commons)

The Fire Is Upon Us represents the most comprehensive account of this debate and its significance, both in the intellectual development and careers of Baldwin and Buckley, and in the ongoing struggle to deal with the legacy of slavery, racial discrimination, and violence in America. Buccola has crafted a dual intellectual biography that engages critically with the writers’ starkly oppositional political philosophies. This book should attract anyone with an interest in the history of African-American literature, civil rights, or modern American conservatism. Working back from this decisive moment in American political history, Buccola delves into the archives to highlight how both men came to view the problem of race in America so differently, and to put this debate in the brutal context of the era.

Structuring and achieving the right balance with a joint biography is a difficult task. Shifting rapidly between two separate narratives makes the first half of this study seem a little disjointed, as if the author were overly concerned about constructing tension too early on. This is more than made up for in the second half, which is at times fascinating, enraging, and deeply moving. Buccola’s commitment to engage with the ideas and arguments of both Baldwin and Buckley (and not just their distinctive public personas) is what makes this book so commendable. Buccola’s approach represents a genuine attempt to understand what both men really believed and why they felt motivated to fight for their competing visions of the country.

In adopting this approach, Buccola lets Buckley’s ideas stand on their own. Like his arguments in the Union hall, they fall completely flat. Buckley’s analysis (in print and in public forums) was frequently illogical, reactive, and personal. It was his quick wit, charm, and uncanny ability to identify and exploit opportunities in the media and in politics that allowed him to occupy such a prominent role in American society. Debating Baldwin at Cambridge, Buckley vigorously attacked him on lines cherry-picked from both Baldwin’s essays and his novels, and yet it is not at all clear that Buckley understood or had even read the works in question. In the age of Donald Trump, it is all too easy to view the icons of twentieth-century conservatism with rose-tinted glasses, yet The Fire Is Upon Us warns against such an approach. Buckley’s public and private thoughts on race and white supremacy are sure to unsettle most readers.

Although much has been written elsewhere on Baldwin’s civil-rights activism and on his writing, Buccola’s analysis is highly insightful and well written. Baldwin’s cultural presence is greater now than it has ever been since his death in 1987, with new audiences engaging with his novels and plays, with the recent film adaptation of If Beale Street Could Talk (2018), and with Raoul Peck’s documentary I Am Not Your Negro (2018). In a crowded field of Baldwin analysis, Buccola delivers, highlighting the relevance of Baldwin’s writing and of his debate with Buckley for the present. Buccola skilfully underscores the urgency felt by both Baldwin and Buckley to either advance or reverse the gains of the civil-rights movement, yet for Baldwin it was about much more. For Baldwin, any denial of the humanity of others meant a denial or destruction of one’s own. That Baldwin’s cultural popularity has surged since 2016 is far from coincidental; it is proof that Baldwin’s warnings about the destructive power of hatred and inequality remain as critically urgent now as then.

Comments powered by CComment