- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The writerly ‘I’ is notoriously fraught and political in non-fiction writing. What are the implications of writing from a biased and limited perspective (as all of us inevitably do)? How to get around – or work within – the constraints of the personal? These questions are ethical ones but also ones of craft. Many memoirists and essayists have grappled explicitly with them on the page.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

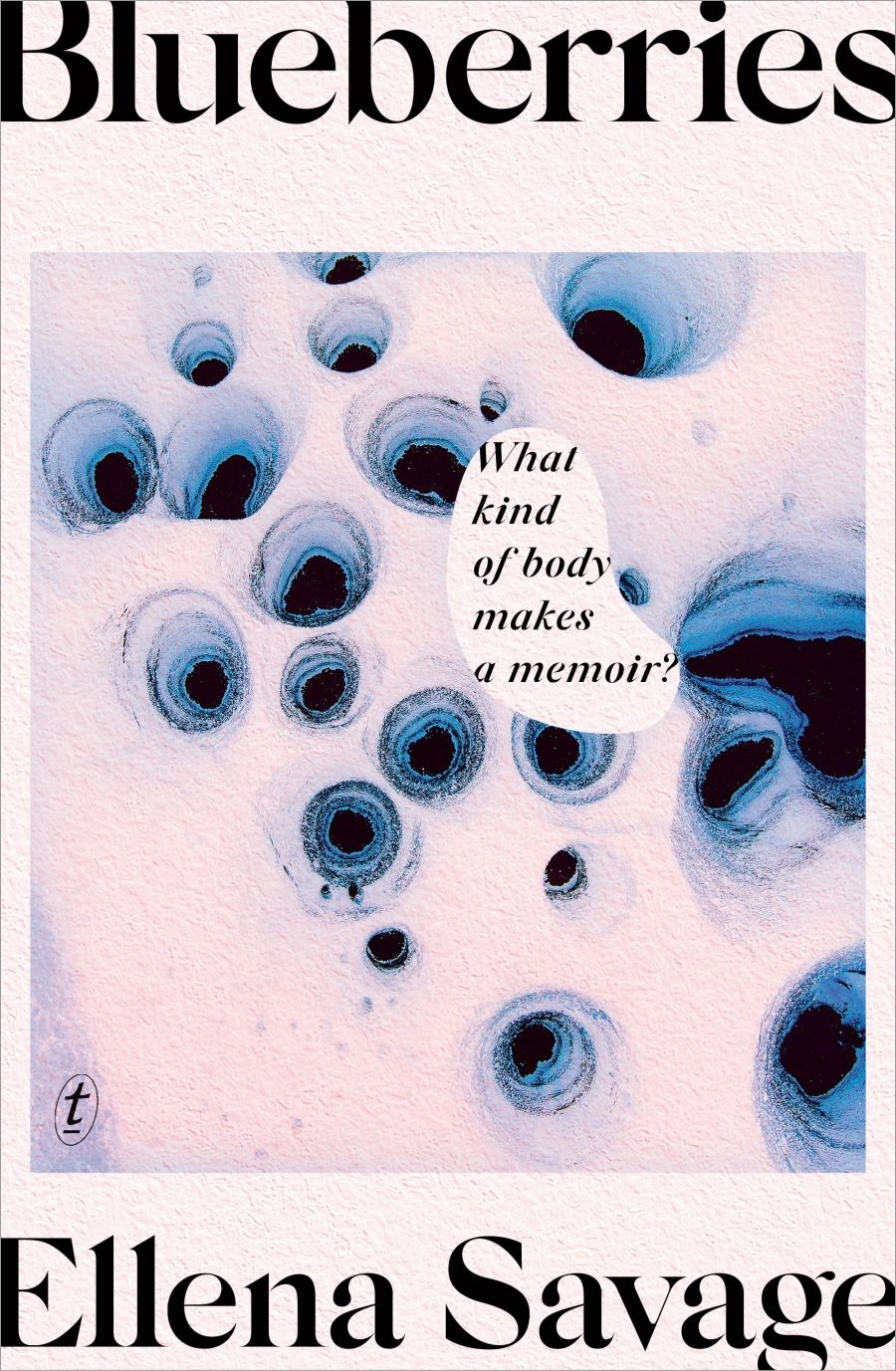

- Book 1 Title: Blueberries

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 256 pp

What follows in ‘Antimemoir’ is not a clear-cut delineation of what ‘antimemoir’ might entail as a literary genre or practice – that would not be Savage’s style. (Joan Retallack writes that the best essays ‘maintain an irritating presence, pleasurable or not, as radically unfinished thought’, and Savage’s essayistic writing falls into this camp.) Three years later, though, we have Savage’s début essay collection, Blueberries.

Ellena Savage (photograph by Leah Jing McIntosh)

Ellena Savage (photograph by Leah Jing McIntosh)

The essays in Blueberries are written and peopled by many of Savage’s selves. Of Kapil’s Ban en Banlieue (2015), Savage writes: ‘Kapil splices the lyric ‘I’, multiplies it, buries key fragments, and then undermines the very composition of the book in its own pages.’

The ‘I’ of the essays in Blueberries operates in the same way. In the opening essay, ‘Yellow City’, Savage returns to Lisbon eleven years after she was the victim of an ‘almost rape’ there. Ostensibly, she is looking for court documents that pertain to the sexual assault case, but the essay quickly introduces voices that question the primary narrator’s intentions, her memories, her honesty. ‘You don’t want to read the police report,’ one accuses; another bluntly tells us, undermining the narrator’s previous paragraph: ‘She’s lying.’ This complicated approach to ‘the lyric I’ calls into question the reliability of memory and the stability of the self, particularly when these things are unsettled by trauma and the passage of time.

Through the shifting subjectivities of Savage’s lyric ‘I’, Blueberries asks piercing questions about power, desire, and violence. The essays explore what it means to be an artist, a body, a woman, a friend, a lover, a daughter – and how these roles intersect with systems of oppression. Each essay has its own form and process, but in each one Savage focuses her sharply analytic eye on the world she moves through – as well as on herself.

In a review (not included in Blueberries) of Leslie Jamison’s memoir The Recovering, Savage writes of Jamison’s ‘form-perfect self-critique’. She suggests that at times Jamison’s writing is ‘perhaps, even, performatively self-flagellating’ and that this tendency ‘leave[s] little room for mistakes or surprises or even those nourishing little indulgences: rage, self-pity, contempt’. This review sits interestingly alongside Blueberries; occasionally, Savage’s own essays are self-critical to the point of being uncomfortable to read. When Savage’s writerly ‘I’ splits across lines of time or perspective, this self-interrogation is especially visceral. For example, having shared – exposed? – the transcript of an email that eighteen-year-old Ellena Savage had sent her older brother after being assaulted in Lisbon, another, more recent self cuts in to mock it: ‘I mean. Who speaks like that?’

All writing is performative, to some extent. Savage’s self-critique, though, is different from the ‘self-flagellating’ she identifies as self-protectively performative in Jamison’s prose. Jamison’s writing is tightly controlled, foreseeing and circumventing potential criticism; Savage, by contrast, tends to write into the dark. Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick writes that the most useful work ‘is likeliest to occur near the boundary of what a writer can’t figure out how to say readily’. When Savage is at her best, this borderline space is where her writing goes to work. The essays in Blueberries set out to interrogate the unknown and to express the inexpressible much more often than they set out to argue or convince, and Savage’s relentless self-critique is no exception to this rule.

The collection’s closing essay is a revised version of ‘Antimemoir’. In a way that feels appropriate to the ever-evolving ‘I’ of Blueberries. It is markedly different from the 2017 version: the ‘I’ has shifted.

The Blueberries version of ‘Antimemoir’ states: ‘Writing in first person is writing that admits that experience is always truncated. That perspective is necessarily incomplete. That it is not possible, not honest, to pretend otherwise.’ This recalls a reason for writing that Savage offers in the Blueberries essay ‘Notes to Unlived Time’: writing is worth doing because it ‘can’t help but demonstrate how dubiously, how erroneously and how enchantingly knowledge is produced, remembered, transmitted’. Perhaps one of her finest achievements in Blueberries is that, through her version of anti-memoir, Ellena Savage turns the fraught subjectivity of the writerly ‘I’ into a formidable tool for reckoning with the self and the world.

Comments powered by CComment