- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is probably no book in a poet’s career more important than his or her first Selected Poems. It is here that poets have the opportunity to display the best of their work in all its variety over several decades. Individual collections are a mere step on the way. Collecteds tend to be posthumous and of interest mainly to scholars, reference libraries, and a cluster of devotees.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

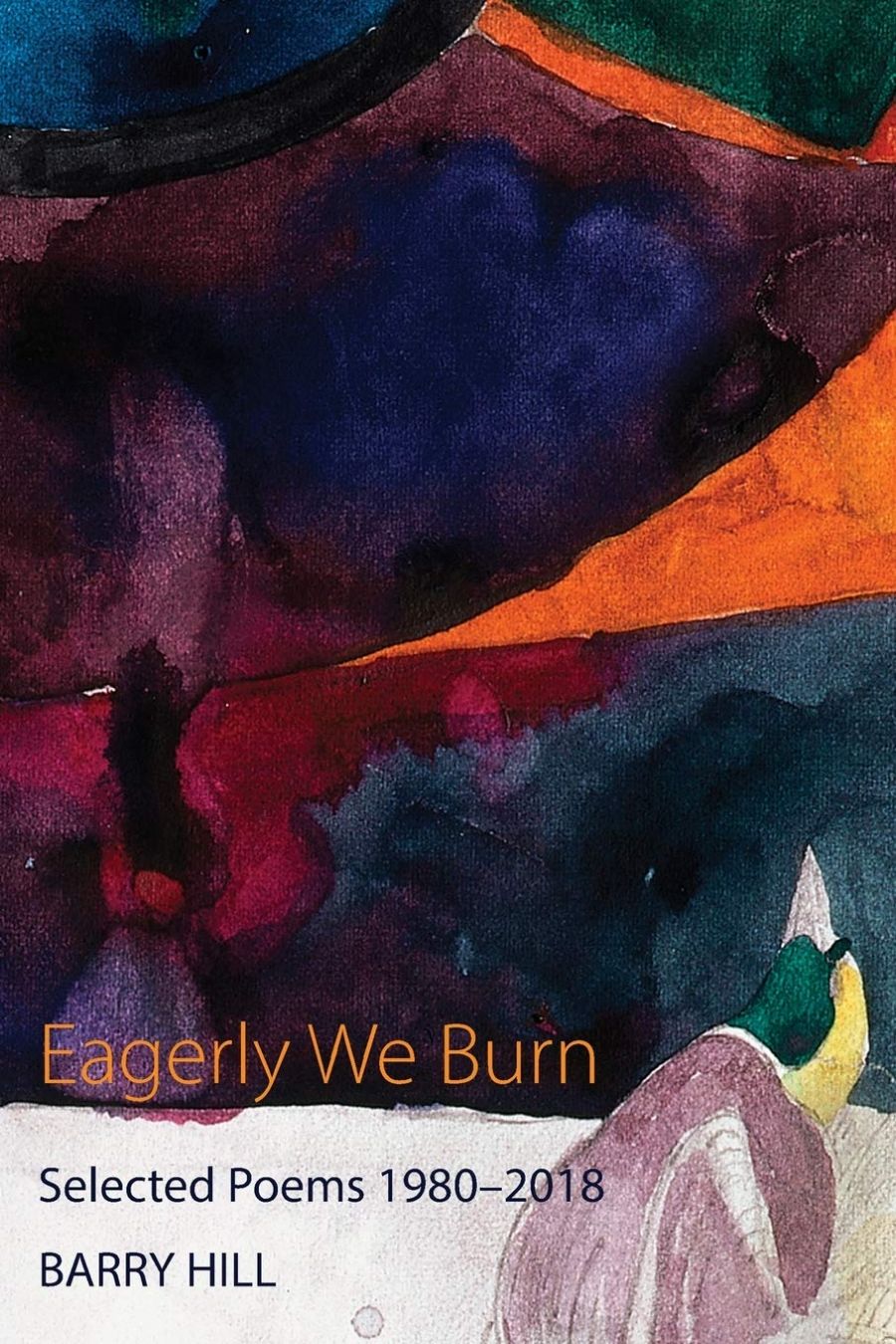

- Book 1 Title: Eagerly We Burn

- Book 1 Subtitle: Selected poems 1980–2018

- Book 1 Biblio: Shearsman Books, $25 pb, 193 pp

Such a reading reveals that Hill’s techniques have remained fairly consistent over thirty years and that his deeper concerns often reappear in different forms over long intervals. In this regard, Hill is drawn, as are the best political poets (for example Bertolt Brecht and Pablo Neruda), to the tension between poetry as a vehicle for personal lyrical expression and poetry’s potential contribution to objective political progress.

Successive books by Hill have embodied one or the other of these tendencies. His first collection, Raft: Poems 1983–1990 (1990), is mainly lyrical love poetry. His second, the well-received Ghosting William Buckley (1993), explores the experiences of the eponymous escaped convict who lived for thirty-two years among the Wathaurung people around Port Phillip Bay. The excerpts here capture Buckley’s initial bewilderment, his gradual absorption by his Aboriginal hosts, and something of their culture – as in their song cycles, of which Hill essays a version in his poem ‘Koim’.

Hill’s preoccupation with Aboriginal cultures is continued in The Inland Sea (2001), set mainly around Alice Springs. As with its predecessor, this book attempts to understand Indigenous beliefs and mores from a close but respectful distance. One of its most affecting poems is ‘Riverbed Song’, short enough to be fully reproduced here:

In moonlight I saw them.

Two in a swag

under the bridge.

His royal sleep.

Her hair flowing

over his happy arm.

A good cattle dog

guarding their marriage.

Hill’s progressive politics, solidly based in the trade union movement of his father, emerge more clearly in his fourth collection, Necessity: Poems 1996–2006 (2007). This focus, which is rare for Australian poetry in these quietist postmodern/conservative times, lends a distinction to Eagerly We Burn as a whole. It may also partly explain why the book has been published in England rather than in Australia.

Something of the tone and complexity of Hill’s political sensibilities can be gleaned from ‘I Know a Poet with a Gun’: ‘What does the poet want? / Love, and money. // When does he want it? / Now. For his power / has gone without saying.’ The poem then ends, enigmatically, with: ‘The poet knows that / in the beginning was the deed. / He must combat this, / and remain useless.’ It seems that Hill considers the role of the political poet to be a committed, attentive witness rather than to prophesy or proselytise.

Another dimension to Hill’s work is that of the empathetic traveller, the poet or scholar who does his or her homework and wants to enter, at least to some extent, cultures very different from his or her own. Four Lines East (2009) and Grass Hut Work (2016) show this in relation to India and Japan respectively. In a telling poem from Four Lines East, Hill observes a rickshaw man washing at a pump on the street and talking casually to another beside him. ‘The listener had a small towel over his shoulder. / He seemed to have all the time in the world ... / A song must have linked the rickshaw men. / But then I had to turn away – / Neither knowing their poem / Nor the wars they might be in.’

In the samples from Grass Hut Work, Hill, with his considerable knowledge of Japanese poetry, seems able to draw closer to his subject. The selections here begin with a notable influence from Bashō. There’s an attempt to break through to the ‘old’ Japan, to understand its continuities with the present version. As Hill confesses in ‘Bashō’s Sin’: ‘In the grass hut / I strive to be nobody / a hungry artist // albeit walking in / my old man’s / peace-mongering steps ...’ It’s another reference to Hill’s influential father who, as a trade unionist, participated in a peace conference in Tokyo in 1972.

Not unrelated to this are the poems in Grass Hut Work dealing with the atomic bomb over Hiroshima in 1945. In a series of poems, Hill manages to evoke again the horror of that particular explosion. The last lines of ‘Crazy Iris’ are among his most forceful: ‘A wild thought at 8.15: / Consider each cicada as a sentient being // In the same instant birds ignited in mid-air. / Mosquitoes and flies, squirrels / family pets crackled / and were gone.’

Eagerly We Burn (not the most appropriate title perhaps in Australia at the moment) also features three impressive sections based on, or around, the art of Lucian Freud, John Wolseley, and Michelangelo. Many of these poems are fine examples of ekphrasis, but there is not enough space to discuss them here.

Comments powered by CComment