- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Twenty years ago, Robert Tickner tried his hand at the nuanced art of political memoir. Taking a Stand (2001) was, he said, ‘an insider’s account of momentous initiatives’ in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs portfolio in the 1990s. A portrait of the politician as a young man, son, father, and husband was not in the offing. Cabinet diarist Neal Blewett, a man not renowned for political flamboyance, described Tickner’s narrative as ‘remorselessly impersonal’. Privately, it seems, Tickner also protested that ‘the public me is not the real me!’

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

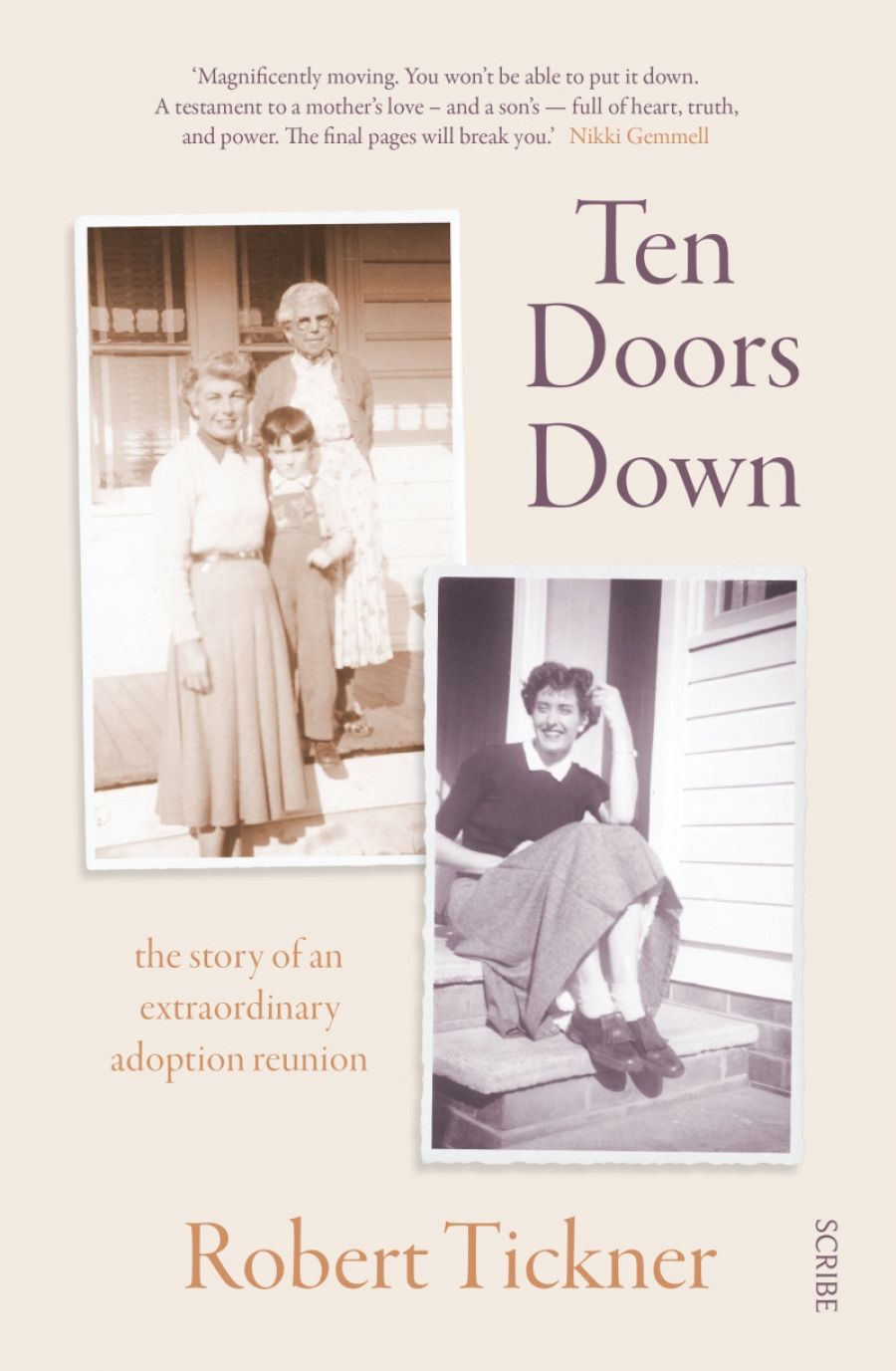

- Book 1 Title: Ten Doors Down

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story of an extraordinary adoption reunion

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.99 pb, 256 pp

In response, Ten Doors Down raises further questions about Tickner, politics, relationships, adoption, and, above all, childhood itself. Maternal relationships form the book’s centre of gravity. Maida records her emotional trauma on learning that, for many years, her lost son had regularly visited a home ten doors down from her own. In her handwritten words, trauma meant ‘NOT KNOWING, NOT DREAMING’ about the coincidences that occasionally brought young Robert so close to her, but never close enough. Tickner, though acknowledging his fortunate upbringing in the semi-idyllic environment of 1950s Forster on the New South Wales coast, comes to understand that for Maida the act of separation imparted a ‘grief and distress that permeated her life’. Tickner reciprocates by allowing Maida to determine the pace of their newfound relationship, as well as that of his paternal self-discovery.

Robert Tickner (photograph via Scribe Publishing)

Robert Tickner (photograph via Scribe Publishing)

Similarly, the maternal relationship with Tickner’s adopted mother, Gwen, figures heavily. He describes Gwen as central to his life, claiming that ‘her way of relating to people was very special’. For Tickner, this relationship, too, was one of deep mutual commitment and obligation. Having received from Gwen an upbringing full of love and warmth, Tickner commits to standing by his adopted mother through the toughest of moments. When dementia rendered Gwen unable to live alone, it was Tickner who managed her move into an aged-care facility, summoning the love that was required to endure the pained cries of ‘Please don’t leave me, Rob’. For Tickner, maternal relationships are about emotional availability and reciprocity.

Though Tickner’s quest was to understand Maida’s ‘story’, the memoir is clearly an attempt to bring coherence to his own self-narrative about his political life. In Taking a Stand, we saw a political agent acting on the world with clear social-justice values but no transparency about the sources of those values. In Ten Doors Down, Tickner reveals the personal experiences and emotions that underwrote his policy decisions. For one thing, his time working for the Aboriginal Legal Service in New South Wales awakened him to ‘the way Aboriginal people have been treated in this country’. For another, his decision to conduct an inquiry into the Stolen Generations is partly explained with reference to his own forced adoption, for the two stories share a common thread in ‘the pain of mothers’. The author recognises, of course, that Aboriginal experiences of child separation were a world apart from his own. Nevertheless, these personal narratives help explain Tickner’s unwavering commitment to Indigenous causes in the 1990s, at a time when other senior members of the Labor government wanted to spend their electoral capital elsewhere.

The memoir also forces readers to consider the emotional sacrifices required in a ministerial life. Notwithstanding the contempt that many Australians currently feel toward their federal MPs, Katharine Murphy was arguably right to remind us that the ‘demands of parliamentary life are unrelenting’. In Tickner we see a man who was, quite literally, trapped in the House of Representatives as his adopted father died, and who was discharging his duties as a local member of parliament when his adoptive mother died. We see a marriage ripped asunder by the huge strain of political life. Further, Tickner’s emotionally demanding quest to meet his birth parents occurs against the turbulent backdrop of bitter debates about Mabo, native title, and the Hindmarsh Island affair. One is left wondering how best to measure and evaluate the public good against the private cost, and the political achievements against the personal trauma.

At its core, Ten Doors Down is concerned above all with the nature of childhood itself. Reflecting on the reprehensible history of forced adoption in Australia, Tickner confronts many problematic historical assumptions about the nature and rights of a newborn child. For psychologists, babies were a blank slate to be acted upon by their environment. For policymakers, babies were verging on a supply-and-demand problem, with too many couples wishing to adopt and not enough mothers wishing to relinquish their child.

Although he ultimately abstains from passing judgement, Tickner’s questions indicate that, for him, motherhood and childhood are, at their most basic level, phenomena of the heart. After all, Tickner’s book is propelled by the question that all children must eventually ask: was I made in her image?

Comments powered by CComment