- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Much political mileage has been made in Australia from the turning back of ‘boat people’. Travel by boat is the cheapest means of getting to this island continent, and the most dangerous. Boat travellers are the poorest and the most likely to be caught and deported or sent to an offshore camp. But their number is less than half of those who arrive by air as tourists and apply for refugee protection: some 100,000 have done so during the seven years of this Coalition government.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

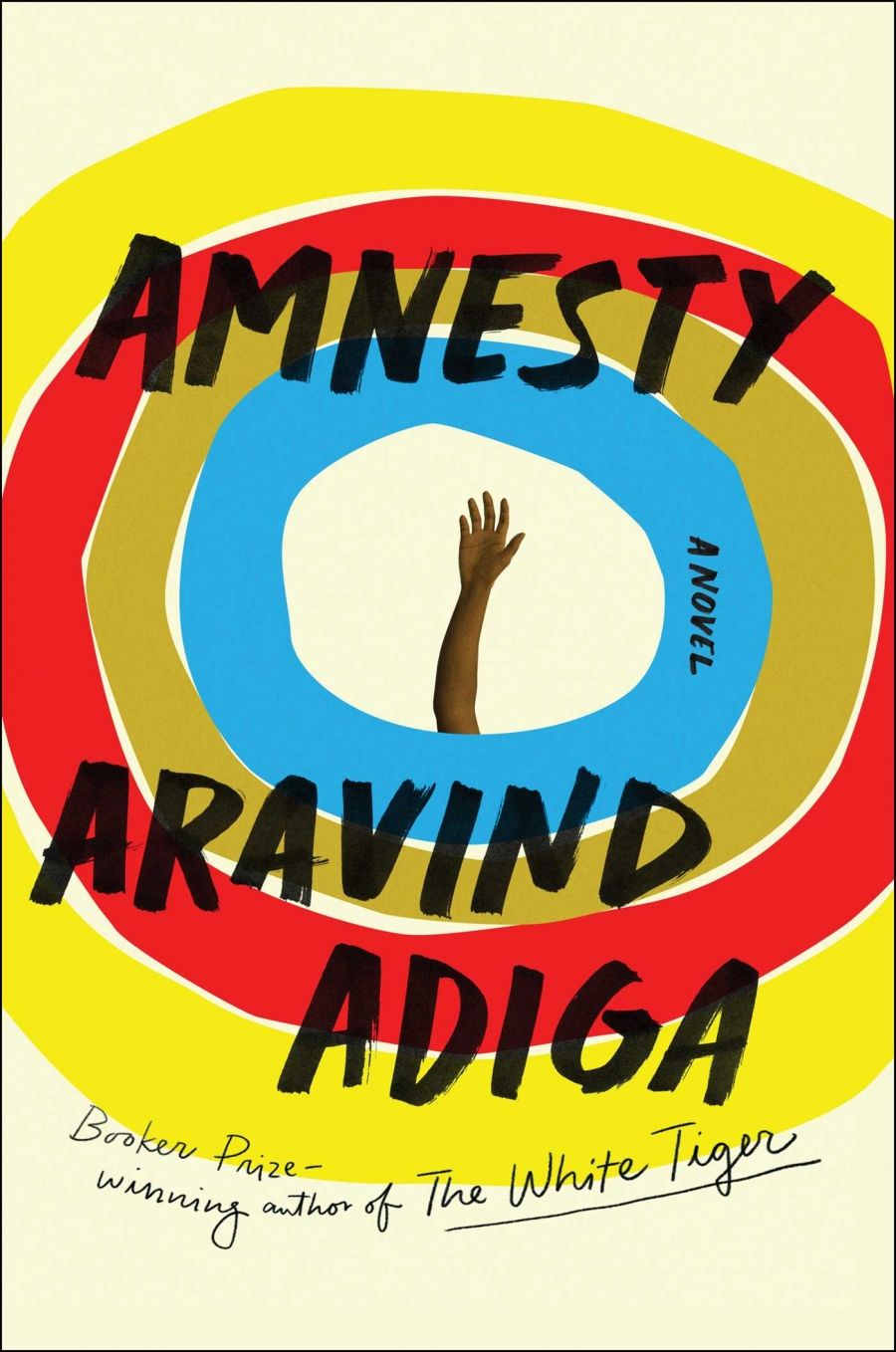

- Book 1 Title: Amnesty

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $29.99 pb, 259 pp

Malaysian Chinese are a special case. In Malaysia, tourists can get a travel authority for Australia electronically from a travel agent, and many of those wanting to emigrate are well-educated Chinese Malaysians seeking better economic and career opportunities. Malaysia, whose official policies favour Malays and Muslims, is ‘full of illegals’, as one of them tells Danny, the Sri Lankan protagonist of Aravind Adiga’s latest – and perhaps best – novel, Asylum. Danny is amazed that Chinese are the underclass anywhere, having watched Chinese drinking champagne on party boats on the Parramatta River.

Adiga’s silence since his last novel, Selection Day (2016), is due to the five years he spent in Sydney, Batticaloa, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Chennai researching the asylum-seeker industry. He introduces two new ways of seeing Australia: through the eyes of legal and illegal residents. Danny can distinguish one from the other in the street, and so can the other illegals. He also detects sub-categories of migrants: junk-food eaters from poor suburbs have broad behinds; slim Indian schoolboys are the sons of Balmain doctors, and they look straight through him.

Adiga is always at his best writing about wealthy Indians and those aspiring to wealth. Two classics of the latter sort are Danny the Legendary Cleaner’s clients. Rhada has defrauded her employer, Medicare, and is out of work. She lets her lover, Prakash, a chronic gambler who sports the tie of a private school he briefly attended, live rent-free in House 6, unbeknown to her Australian husband, Mark, in House 5. Danny was exploited for a year in Dubai, and on his return was tortured by Sinhalese interrogators who mistook him for another Tamil with the same name, Dhananjaya Rajaratnam. The result, a swollen scar on his arm, should be proof enough that his fear of persecution is justified and thus enable him to get him a protection visa in Australia, but after being ripped off at a Wollongong tertiary college, he applies for an extension of his student status and is rejected.

Danny’s interview with Immigration is based on a real-life transcript in which an officer states that Australia has ‘zero tolerance for illegal activity of any kind’. Danny learns that he will be caught, billed for his unpaid tax and costs of detention, and deported. All Danny wants is to live in Australia, where he won’t be like everyone else but will be a ‘wanted minority’. Nothing in Australia is hard to understand, Danny the non-drinker, non-smoker decides, ‘once you know that all the young people have glassy blue eyes because they’re on drugs’. To sound Australian, you put a loud ‘Look’ at the beginning of a sentence, and ‘ridiculous!’ at the end.

For four years, Danny has survived as an illegal, keeping his Vietnamese girlfriend ignorant of his status while he lives in dread. The novel tracks Danny through one entire day in Sydney, from Glebe where he lives in a tiny room above a shop, to Erskineville, Newtown, Potts Point, Darlinghurst, Pyrmont, and Hyde Park. Tommo, his Greek landlord, tyrannises him just as his father did. Prakash, the big, tough gambler, threatens him on his battered mobile every few minutes from morning till evening, and stalks him through the Kings Cross dives. At last, Danny defies Tommo, turns on Prakash, and attacks him ‘as a lion attacks its trainer’.

This solves nothing. If Danny goes to the police, either Prakash or Tommo will report him as an illegal. Me no dob, you no dob, is the law of the immigration jungle. Prakash used to make Danny wait under the Coca-Cola sign while he and Rhada made love. The sign pulsates all day and night; throughout the book it looms over Danny’s peregrinations like the spectacles advertisement in The Great Gatsby.

Wandering into a courtroom, Danny listens as justice is calmly done for someone he doesn’t know. He’s impressed by Australian fairness. In his refuge, the Glebe Public Library, Danny learns that Malcolm Fraser in 1976 declared an amnesty for illegals. He survives in the hope that fairness may happen again. Ridiculous.

Comments powered by CComment