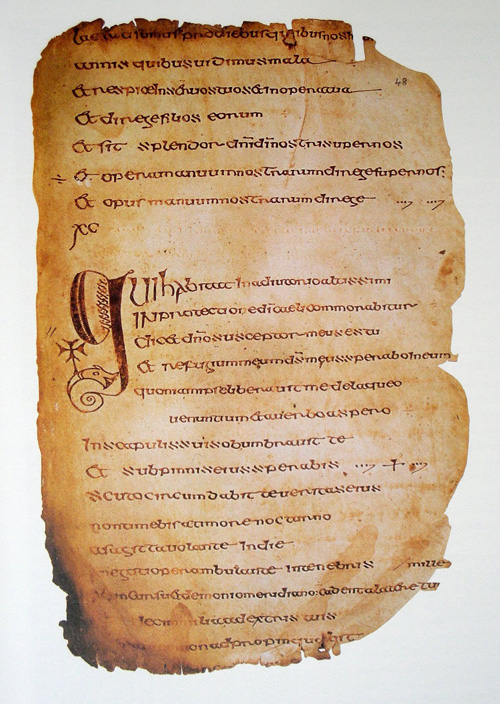

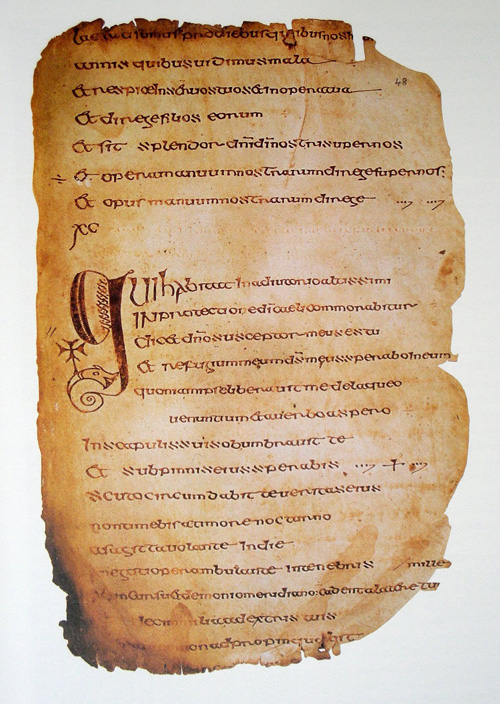

The most precious manuscript held by the Royal Irish Academy is RIA MS 12 R 33, a sixth-century book of psalms known as an Cathach (‘The Battler’), or the Psalter of St Columba. It is believed to be the oldest extant Irish psalter, the earliest example of Irish writing – and the world’s oldest pirate copy. According to tradition, St Columba secretly transcribed the manuscript from a psalter belonging to his teacher, St Finian. Finian discovered the subterfuge, demanded the copy, and brought the dispute before Diarmait, the last pagan king of Ireland. The king decreed that ‘to every cow belongs her calf’, and so the copy of a book belonged to the owner of the original. Columba appealed the decision on the battlefield, and defeated Finian in a bloody clash at Cúl Dreimhne. No trace remains of Finian’s original manuscript, if it ever existed. Only ‘The Battler’ survives.

Finian v Columba is difficult to reconcile with modern copyright law. The psalms in question were attributed to God, revealed to David, and translated by St Jerome in the fourth century, so Finian’s claim to copyright in the work is unclear. It may be that the pagan Diarmait simply free-associated his judgment from the calfskin of the Cathach’s pages. But any want of judicial rigour is surely redeemed by the king’s early intuition that there is something valuable about a book beyond its physical self, that it has spirit as well as flesh and a soul beyond its body – as well as by the delicious consequences of an actual military war being fought, at least in part, over a single illegal copy, and of that outlawed copy becoming a national treasure.

The issue of copyright protection hardly resurfaced for another eight hundred years, not so much because an author’s skill and effort went unvalued, but because the technological and economic conditions never allowed copying to become a significant problem. The skill and effort involved in manuscript production meant that it was hardly cheaper to pay a scribe to copy a work than to commission a new one, while the patronage system ensured that authors were paid and encouraged to write even if their work was copied. And, of course, the demand for pirated books was constrained by the fact that hardly anybody could read.

Much of that changed with Gutenberg’s metal movable-type printing press, which had spread across Europe by about 1480. Suddenly, books could be cheaply bought rather than expensively commissioned. Literacy soared, and a proper market for books came into being, with the same basic economics that operate today. That is, while great effort and capital were still required to make the first copy, the incremental cost of every subsequent copy dropped almost to nothing.

These calculations applied even more compellingly to the first commercial pirates, who found that they could avoid much of the cost of the first copy. They still had to invest in a press and obtain one copy of a book or play – preferably a proof copy filched before the official release – but once they had laid out the slugs of type, they could stamp and sell as many copies as they pleased. And they did: enterprising pirates like Harry Hills, Edmund Curll, and William Rayner quickly scourged the nascent industry, and were thrashed and tossed in blankets for ‘copy-stealing’.

To every cow belongs her calf. In 1557 the Stationers’ Company of London received its royal charter to regulate the industry, and to maintain a register of publishers’ exclusive rights over certain works. These rights only had to be asserted, rather than proven, and they belonged firmly to the publishers. But the publishers contracted with the authors, for the most part, and the Stationers’ Company patrolled the alleys off Fleet Street and Grub Street for secret presses and unauthorised copies. These efforts seem to have kept book piracy at a containable level until the Statute of Anne gave authors rights in their own creations for the first time in 1710.

Copyright law was invented to protect books in an age of great technological change; over the next three centuries, books hardly changed at all. The novel was invented; there was Robinson Crusoe and Pride and Prejudice and then Ulysses and Infinite Jest. There were A-formats and trade paperbacks; and the handwritten manuscripts and trays of type gave way to word processors and Adobe InDesign. Instead of buying a book from a printer’s house, we had Borders and Big W and Amazon. But the book remains fundamentally the same: sheets of paper printed with ink and bound together into a codex as of time immemorial. The industrial processes have changed, certainly the marketing has changed, but the product hasn’t changed.

This consistency seems remarkable considering the waves of technology that have transformed other artistic industries. Music has advanced from sheet music and pianola rolls to wax cylinders, vinyl records, cassettes and 8-tracks, compact discs, and now digital files stored on hard drives or streamed through the air itself. The quaint cinematograph films of the Copyright Act were enlivened by sound and Technicolor, migrated from cinemas to videotapes, laserdiscs, DVDs and Blurays, and ended up as digital files on the same drives and servers as our music.

These have been tremendous developments for consumers, giving us instant access to music, television shows, and films from anywhere in the world, not only in the comfort of our homes but also in the tedium of bank queues and long-haul flights. They have opened up exciting new streams of revenue for the creative arts. But what’s good for the duly licensed goose is at least as good for the piratical gander, and the recent revolutions in music and film have spurred an increasingly frantic Red Queen’s race and transformed international copyright law and enforcement.

The problem is that the reduction of musical and cinematic works to high-resolution digital files has made it possible for anyone to copy a song or a film an infinite number of times with perfect fidelity. In the old days you might tape a track off the radio or a friend’s tape, but, because the tapes were analogue, each copy would come out worse than whatever it was copied from. That AC/DC bootleg would be almost unlistenable by the time it got to you. But the CD and the DVD are digital, so every copy is identical to the original – apart from the shiny disc itself, and the jewel case, and the cardboard insert, and even those have vanished from the digital downloads of the iTunes Store and its competitors. And the ubiquity of the high-speed Internet now means that you no longer need to know someone who knows someone who bought the original album or movie. There is no need to stop off in Bangkok or Chinatown for that mysteriously cheap box set. You just need to search for it, on a BitTorrent tracker, on the repurposed Usenet, on Google. Now the whole world is your generous, shifty friend.

At the same time, the shifting economics of music and film production mean that the first copy of the average movie or studio album has become galactically expensive. A thousand people might work for a year on a Hollywood blockbuster. A million shareholders might be clamouring for a return in an industry where hits are almost impossible to predict, where nobody really knows how to make a song that people want to hear or a movie that they will want to see, except by spending tens of millions on marketing, production values, special effects, and franchises.

Little wonder that copyright law and enforcement have been spun into a frenzy. The shelf life of copyright was as little as fourteen years under the Statute of Anne; now it is life plus seventy years for a human author, ninety-five to one hundred and twenty for a corporation. It may keep on being extended as valuable properties threaten to fall into the public domain. The scope of exclusive copyright has extended into an expanding range of derivative works, while the categories of fair use have been more tightly restricted. The penalties for downloading a song or a movie are now orders of magnitude heavier than for stealing the same content on a physical CD or DVD – though only an infinitesimal proportion of online infringements are detected, let alone prosecuted.

Most of these changes have technically applied to books as well as to music and film, but the publishing industry has never pushed for copyright reform with anything like the fervour of Hollywood or the record labels. Authors and publishers have long worried that people aren’t reading any more, that newspapers aren’t reviewing, that bookshops are closing; but they’ve been reasonably sanguine about copyright, because for hundreds of years copyright has done a pretty good job of protecting the books it was invented to protect. Thanks to scanning and optical character recognition and computer typesetting, commercial pirates no longer need to arrange any slugs of lead by hand – but printing costs are still substantial, distribution is difficult and easily detectable, and commercial piracy is generally limited to developing nations whose governments see copyright enforcement as a low priority. And individual book piracy is more or less impossible: you can photocopy a book or scan it into your computer, but the results are hardly worth the effort.

Now the whole world is your generous, shifty friend

For centuries this has been the book’s best protection. Like King Diarmait, we know that the essence and value of a book is not limited to its material form. But the body and soul of a book are bound together in complicated ways, and entangled with our own bodies and souls beyond that. The physical shape of the book has shaped our architecture, our furniture, our muscles and tendons, our neural pathways; the way we sit in a library or reading room, with a lamp and a chair; the way we curl up in bed. So much of our reading is specific to the physical book, and the physical book is almost impossible to copy. A stack of unbound photocopied pages, a window open in Microsoft Word or Acrobat Reader, a badly pirated book whose lines slope, whose cover is not pleasing, whose spelling is approximate – none of these are substitutes for the true book. None of us can make a copy of a book that is anything like a book, and so the book has remained secure while music and movies have demanded ever more protection from ever more ambitious copyright legislation. Unlike its precarious cousins, the book is safe from copying. At least, it was.

Electronic books came to the prehistoric Internet with Project Gutenberg in 1971, but it wasn’t until 1998 that the first dedicated electronic readers appeared. The NuvoMedia Rocket eBook had a 14.5-centimetre monochrome screen, was 3.8 centimetres thick and weighed about 600 grams; its four megabytes of flash memory could hold ten novels. The SoftBook had a 24.1- centimetre greyscale screen and a built-in modem that plugged into a phone socket and downloaded books at nearly 100 pages per minute; it weighed 1.3 kilograms. Both were clunky and hard to read, with jagged text and low contrast; they look more than anything like the original Etch A Sketch. The time and effort needed to load a new book hardly encouraged impulse buying. Even the manufacturers downplayed their threat to the traditional book market.

‘In the same way videotapes didn’t stop people from going to the movie theatre, the e‑books won’t stop people from wanting books,’ the CEO of SoftBook predicted. And he was right but not for long. In 2004 the Sony LIBRIé EBR-1000EP was launched in Japan as the first device to use electronic ink, giving significantly clearer and more readable text with minimal power drain. Sony’s PRS-500 Reader was released worldwide in 2006, followed by Amazon’s Kindle in 2007. The new generation of devices had high-resolution 15.2-centimetre screens and weighed less than 300 grams, and as they ran quickly through their iterations – joined by Barnes & Noble’s Nook in 2009, the Kobo in 2010, and cute contenders like the iLiad along the way – they grew sleeker and more streamlined, their storage increased a thousandfold, they added built-in wireless connections to online bookstores, and people started buying them.

In 2010 Apple launched its first iPad. It was billed as an all-purpose device and used a 24.6-centimetre laptop-style liquid crystal display rather than electronic ink, but Apple demonstrated that it was aiming, at least partly, at the reading set by confining the iPad’s display dimensions to a book-friendly aspect ratio and launching its own electronic bookstore. A range of similar tablet devices soon followed from almost all quarters, many using Google’s Android operating system. Most of these tablets can be used to purchase and display books from most of the online bookshops, so you can read your Kindle, Nook, or Kobo books using dedicated iPad and Android apps, though Apple’s restrictions prevent these apps from helping you to buy new books, and you can’t read iBooks on any tablet apart from the iPad.

These devices are slowly becoming appealing objects, more of a pleasure than a chore to cradle, to swipe, to flick. They’re about the same size and weight as a hardback or a paperback, though much thinner; many people dress them in tactile leather or fabric covers to make them seem more like books. They fit with you on a sofa; they’re at home on a bedside table. Reading on their screens isn’t quite the same as reading a real book, and swiping the screen or clicking a button isn’t at all like turning a page. You don’t get the sensory feedback of two handfuls of paper to let you know how far into the book you are getting: film critic Roger Ebert has compared the experience to running on a treadmill. Early studies have suggested that it takes slightly longer to read an electronic text, and we may remember less of what we read.

The Sony Data Discman (1991) was marketed as an ‘Electronic Book Player’ (Jak Boumans Collection)

The Sony Data Discman (1991) was marketed as an ‘Electronic Book Player’ (Jak Boumans Collection)But, for the first time, we have alternatives to paper books that are at least somewhat like paper books. A Nielsen Norman Group survey found that readers reported around the same level of enjoyment from reading on an iPad, a Kindle, and a printed book, giving the experience 5.8, 5.7, and 5.6 out of seven respectively. Reading on a traditional computer screen rated only 3.6, suggesting that electronic

readers feel much more like books than like the desktop computers and laptops whose underlying technology they share. Many people who swore they could never read a novel on a computer screen are now finding that they can, as long as they can hold that screen in their hands.

Increasing sales of electronic books seem to corroborate these reports. Amazon sold more e‑books than hardbacks in the quarter to July 2010, more than paperbacks in the quarter to January 2011 – and more than printed books, hardback and paperback together, in May 2011. As an online bookshop, Amazon is not representative of the whole market, but the 2012 BookStats survey reported e-book sales in the United States at thirty per cent of adult fiction revenues, the highest of any individual format. HarperCollins has reported e-book sales at fourteen per cent of worldwide revenue, Penguin at nineteen per cent, and Simon & Schuster at twenty-one per cent. It is not yet clear at what level these figures will stabilise.

An electronic reader will never evoke the same emotions as a paper book. It will never feel the same, will never give off the aroma of new ink or old dust, won’t yellow with age, won’t hold your ticket stubs or postcards. Sometimes that will matter a great deal, but sometimes not nearly as much. Some books are all about the page, the texture of the page, the image on the page, the turning of the page. But some books are almost entirely about the words, the characters, the stories themselves. They are much more spirit than flesh, more soul than body, and to read them on an electronic reader might not be death but perhaps apotheosis. And an electronic reader can hold a hundred thousand of them, and summon new ones as fast as you can think of them. For many books, and many readers, this is proving to be worth the compromise.

Videotapes didn’t stop people from going to the movie theatre, but sixty-inch plasma screens with surround sound and high-definition movies are making a dent. Nor did the Rocket eBook and the SoftBook stop people from wanting books, but the latest Kindle and the next iPad – and whatever else is around the corner – just might.

The book is changing for the first time in centuries, and its transition to a digital format may prove almost as transformative as its first industrialisation with the printing press. Anything made of digital bits can be copied perfectly and sent across the world in an instant. If an electronic book on a handheld reader is a satisfactory approximation of a real book – not nearly such a big ‘if’ as it used to be – then for the first time books can be copied to a satisfactory approximation by anybody, with no effort. As always, this is terrific for publishers and authors, but even better for pirates. The good news is that commercial piracy is more or less doomed: nobody’s going to pay for a knock-off when they can get the same thing for free. The bad news is that personal, individual book piracy is certain to go through the roof.

The bad news is that personal, individual book piracy is certain to go through the roof

That black ship may have sailed already. People have been sharing unwieldy PDF scans of J.K. Rowling’s books since Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2003).Eager fans shared their own unauthorised translations long before the approved versions became available, and digital photographs of every page of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007) appeared online days before the official street date. Dan Brown’s The Lost Symbol (2009) turned up on file-sharing sites within twenty-four hours of its release, and was reportedly downloaded 100,000 times within three days. Online investigator Attributor estimated that nine million books had been downloaded illegally in the last months of 2009, though the basis of this estimate is unclear, and the company appears to have shifted to more defensible metrics like the increase in the number of times users search Google for free e‑books – up fifty per cent in the year to October 2010.

At this point we must assume that every moderately successful book published in an electronic format – surely every moderately successful book from now on – will very quickly be available, illegally, for free. It takes seconds to download a book beautifully formatted and packaged by the publisher, seconds to strip away any digital rights management so that anyone can read it on any device, and then seconds to upload it again. The spread of music and then movie piracy was at least slowed by the size of the files and the speed of yesterday’s Internet. An e‑book wouldn’t even dent the data allowance on your mobile phone.Compared to the PDF scans of the early pirate scene, the e‑books now for sale on the iBookstore or the Kindle Store are things of efficient beauty, often exported straight from the InDesign master file and marked up precisely to preserve headings and subheadings, chapter breaks, and hyphenation points. They may include bitmapped illustrations, but they are mostly text, doled out a byte at a time into tiny treasures. When you see them on your hard drive, you think there must be a mistake. All those years of research, those interminable hours before the blank screen, the blinking cursor – and it only takes up 400 kilobytes? And half of that is the cover image? A four-minute song from the iTunes Store is twenty times bigger, a ninety-minute movie ten thousand times bigger; and these are the files the torrents and digital lockers are built to fling around. The entire Western canon is as nothing to these shovellers of digital information – less than an episode of Everybody Loves Raymond.

So while the book has taken longer to fall than music and movies, it will fall faster. Every couple of days, some person or group called NERDs uploads a couple of hundred new books to the alt.binaries.e‑books newsgroup in the shiny EPUB and Mobipocket formats used by the iPad, the Kindle, and the rest. Tim Winton is there, and Kate Grenville, Colleen McCullough, Christos Tsiolkas, Steve Toltz, David Malouf, all of Peter Carey. It is not yet the case that you can get everything you want, especially for authors without international publishing deals. But it won’t be long.

Books that cost time, effort, and money to produce are now available gratis. How much of a problem is this? Nobody really knows. Attributor estimates that piracy cost the publishing industry $US2.8 billion in 2009 – but they don’t know. In December 2010 the Association of American Publishers reported that ten of their publishers had paid $778,000 to online monitoring services who identified 299,000 infringing titles online – but there is no way to know how often these e‑books were downloaded, and even less chance of knowing how many of those downloads represented lost sales, and how they might interact with future sales.

Authors who claim that piracy is not a problem at all, that every downloader is a potential new fan bound to buy the next book or recommend all the books to all their friends, just don’t know. Paulo Coelho has set up his own site collating pirate editions of his books from the BitTorrent networks. ‘Since then, my books have sold about 140 million copies worldwide,’ he says. He doesn’t know how many he would have sold otherwise.

Neil Gaiman thinks that releasing a free digital copy of American Gods (2001) increased sales by three hundred per cent, and he no longer fears piracy. ‘It’s people lending books. And you can’t look at that as a lost sale,’ he says. ‘What you’re actually doing is advertising. You’re reaching more people. You’re raising awareness … And I think, basically, that’s an incredibly good thing.’ But he doesn’t know. Cory Doctorow says half a million free downloads of his Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom (2003) helped the book through five physical print runs. ‘Giving away books costs me nothing, and actually makes me money,’ he says. Maybe he knows. There is a growing body of anecdotal evidence. But nobody really knows whether that kind of strategy will work for all books and all authors, or whether it will work for long.

We do know – we ought to know – that we can’t stop people from pirating books, at least not by force or the threat of force. There are ever more ingenious ways to share digital information on the Internet, ever faster, ever more convenient, ever stealthier. There are ways to do it that simply can’t be detected. The pirates who get caught are the dilettantes and dabblers, the least serious pirates. The serious pirates never get caught. The most visible aggregators and indexers and linkers get taken down, but new ones spring up immediately. The dying Suprnova gave way to Mininova, out of whose ashes rose Monova, and there are plenty of cute names left. The online monitoring and take-down notices and scattergun lawsuits can’t do much, if anything, to reduce the availability of pirate material.

Perhaps the best these measures can hope for is to keep the issue alive in the media and the cultural discourse, reminding uncommitted pirates of the effort of artistic creation and the livelihoods at stake, and perhaps giving them just enough pause to consider paying for what they could have for free. Novelist Chris Cleave believes that people pirate books out of ignorance. ‘They don’t do it because they are evil but because they don’t understand,’ he told the Guardian in March 2011. Crime writer David Hewson thinks all we might need is a campaign to remind readers that ‘People who love books don’t steal books.’ They are hopeful, maybe with reason. Readers and authors have a particularly intimate relationship, and perhaps a uniquely loyal one. It is the author’s voice in the reader’s head, singing worlds into being. When you read a book, it can feel as if it was written for you alone. It’s not hard to appreciate the personal effort involved. Maybe readers don’t even need reminding – maybe that’s not the problem.

People who love books don’t steal books. But, you know, they might lend or borrow books, they might sample books and only pay for the ones they do love, they might torrent a book they have already bought in hard copy, they might pay what they think they can afford. They will do these things whether we like it or not. And it’s probably not in our interests to treat every illegal download as an act of aggression. As an empirical matter, it may turn out that that download has led to a handful of legitimate sales. Or it might not. We just don’t know. We can be pretty sure that insisting thatbook-lovers are our enemies will be self-fulfilling and soon self-defeating.

The first war over copyright was a real flesh-and-blood war, and the pirate St Columba won it decisively. The copier won and the copy survives; the owner lost and his book was lost. It is not clear that anything has changed since then. We won’t win any war against those who would read our books without paying for them. All we will do is lose their hearts and their minds when we can least afford it.

For all that, relying on readers’ charity or moral sense doesn’t make much of a business case. When every book can be downloaded gratis easily and undetectably, nobody is going to pay because they have to, and not enough people will pay because they think they ought to. They are only going to pay because they want to. And they will only want to if legitimate, paid downloads are at least as attractive as illegal ones.

That does not mean they have to be free. The great advantage of legitimate downloads is their convenience. Search the bookstore, click a button, and start reading. You can do it all on the device itself, on the couch, on the bus. You don’t need to go near your computer, install any software, or navigate the backwaters of the Internet, where every download might be a virus and every site might be an online piracy monitor’s honey-pot. You don’t need to give your details to questionable private sites or convert any exotic file types. That has to be worth something – and to many people it will be worth a lot.

Weighing against that convenience is the fact that most legitimate e‑books are restricted by digital rights management. Most people won’t care yet, but it is going to become more of an issue as a growing number of readers discover that they cannot transfer their old e‑books to their new gadgets, or as e‑bookstores go bust and leave their books forever undecryptable. Almost every DRM scheme can be bypassed, but it is often easier just to download an illegal copy, and it will be dangerous to encourage readers in that direction. DRM has already been abandoned for digital music, and its continued attachment to e‑books is a sign of the industry’s immaturity. Harry Potter e-books from J. K. Rowling’s official website are watermarked but not encrypted by any DRM, as if the most pirated author on the Internet has realised that we don’t need to give people any extra reasons not to pay for e‑books.

E‑books without DRM will be more convenient than illegal downloads, but for many people they won’t be $14.99 more convenient. The perception that intangible e‑books should be considerably cheaper than physical paper books may be unfair, but it is not likely to change. We know that the true value of a book is in its spirit, its words, and that these have been wrought in tears, edited by sages, and marketed by magicians – but nobody else cares. They only see that there is no ink and no paper, no gilt cover, no warehouse rented, no petrol expended on trucking, no bookshop real estate occupied, and nothing that can be lent to a friend or sold later. They fetishise the body – who could blame them? – and feel that an e‑book is a lesser thing and should cost less. Much less. And they are not just comparing them to new hardbacks or new paperbacks; they are also looking at second-hand paperbacks from AbeBooks or the Amazon Marketplace or eBay. That’s not fair either, but those prices are listed right there beside the e‑book prices. We may not need to match second-hand prices, but it will be dangerous to stay too far above them – remembering that author and publisher receive nothing from the sale of used books.

Readers and authors have a particularly intimate relationship, and perhaps a uniquely loyal one. It is the author’s voice in the reader’s head, singing worlds into being

A second-hand backlist paperback from an Amazon seller goes for as little as $4 shipped, and that might be something like the ballpark for older e‑books. Even now, the Kindle Store’s bestseller lists are dominated by ninety-nine cent books. Those still in copyright are almost all self-published, and not as polished or, let’s face it, as good as most trade books. But they still get dozens of reviews, mostly positive ones, and they are almost certainly making more for their authors than they would if they listed at $9.99 and nobody ever heard of them. Young Adult writer Amanda Hocking says she sold 450,000 e‑books in January 2011 alone, pricing them between the $0.99 and $2.99 familiar from the iTunes Store. Stephen Leather sold 40,000 books in a month at $0.99 each, H.P. Mallory sold 70,000 books at $0.99 to $3.99, and J.A. Konrath 100,000 at a range of price points between $0.99 and $7.19. Under the Kindle Direct Publishing model, the author keeps seventy per cent of revenues for books priced between $2.99 and $9.99 and sold into Amazon’s main geographical markets, and thirty-five per cent for all other Kindle books, and pays Amazon a few cents for delivery. Even assuming most of these sales are made at the cheapest price point, a hundred thousand books at thirty cents each is not a terrible proposition for the author.

A page from ‘The Battler’, which is held at the Royal Irish AcademyBooks are not like music tracks, and they are not like the mobile apps that make millions at ninety-nine cents apiece. But they might be more like them than we think. The first copy is expensive to produce and all the other copies are free, so even a very low price might turn out to be profitable with sufficient volume, and the optimum price might be lower than we imagine. There is room and opportunity to experiment here. Most e‑books are now sold on an agency basis, under which publishers set the retail price of each title and take a fixed percentage of that price. This shift from the traditional wholesale and retail model was won through impressive brinkmanship when Apple’s iBookstore first threatened the Kindle Store, and is now the subject of a Department of Justice lawsuit, which has been settled by some of the publishers but is being contested by Macmillan and Penguin, and exempts Random House. The big publishers have taken advantage of their new pricing power to keep e‑book prices relatively high, usually between $9.99 and $14.99 for recent fiction. The equilibrium price is probably lower, and the publishers could more profitably use their power to explore different price points and track the results of dynamic pricing changes more accurately than they could with printed books. In August 2011 Harper Perennial offered twenty recent e‑books for ninety-nine cents each through all the major stores; it will be interesting to see whether similar promotions will follow.

A page from ‘The Battler’, which is held at the Royal Irish AcademyBooks are not like music tracks, and they are not like the mobile apps that make millions at ninety-nine cents apiece. But they might be more like them than we think. The first copy is expensive to produce and all the other copies are free, so even a very low price might turn out to be profitable with sufficient volume, and the optimum price might be lower than we imagine. There is room and opportunity to experiment here. Most e‑books are now sold on an agency basis, under which publishers set the retail price of each title and take a fixed percentage of that price. This shift from the traditional wholesale and retail model was won through impressive brinkmanship when Apple’s iBookstore first threatened the Kindle Store, and is now the subject of a Department of Justice lawsuit, which has been settled by some of the publishers but is being contested by Macmillan and Penguin, and exempts Random House. The big publishers have taken advantage of their new pricing power to keep e‑book prices relatively high, usually between $9.99 and $14.99 for recent fiction. The equilibrium price is probably lower, and the publishers could more profitably use their power to explore different price points and track the results of dynamic pricing changes more accurately than they could with printed books. In August 2011 Harper Perennial offered twenty recent e‑books for ninety-nine cents each through all the major stores; it will be interesting to see whether similar promotions will follow.

Naturally, publishers do not want to price e‑books so low that they cannibalise sales of printed books, particularly the higher-margin hardbacks and trade paperbacks. BookStats reports that adult hardback and trade paperback sales in 2011 were down by $471.2 million, while e-books were up by $488.9 million. It seems reasonable to assume that a significant proportion of these shifts derive from the substitution of e‑books for more expensive hardbacks and trade paperbacks. But if publishers are so far managing to maintain their overall revenues, we may already be some way towards an iTunes model, where revenues per unit are lower but volumes are much higher – and surely every author would prefer more readers for the same royalties. Anyway, if current trends continue, the idea of e‑books cannibalising printed books will start to look a little quaint. For many readers, an e‑book is already preferable to a hardback; they are already used to sneaking a chapter on their mobile phones and having their bookmarks synced back to their Kindles. They already want all their books everywhere they go. The best way to ensure the continued viability of paper books at anything like current prices may be to include a free e‑book download with every paper version sold. Otherwise it won’t be cheap e‑books doing the cannibalising: it will be free pirated books.

There are other options available. Some kind of subscription service might provide at least a partial answer: an infinite library that allows you access to all the e‑books in the world for a flat fee. In the United States, Hulu Plus and Netflix offer unlimited streaming access to a wide range of movies and television shows for $7.99 per month, and Amazon Instant Video offers a similar package at no additional cost to its Amazon Prime members. In a number of territories Spotify and Sony’s Music Unlimited provide streaming access to up to fifteen million music tracks from $4.99 a month, exactly the initial equilibrium pricing suggested by MIT research in 2003 and proposed by the Open Music Model as the most sustainable model for digital music distribution.

It is not clear what kind of subsidies might be at play here, on the part of either the distributors or the creators of the content; Spotify is part-owned by record companies and is notorious for paying fractions of pennies to its artists, who have to hope that streaming leads to outright sales. But to have all the world’s books available in electronic form for, say, $100 a year would surely be more appealing than piracy for anyone who really loves books, especially if the subscription were bundled with a discounted e‑book reader, a 3G data contract, or a broadband plan. That might help more people to love books. It might help authors find new audiences throughout the world. And it might even help the publishers to maintain their support for authors in this uncertain new landscape. It might help keep body and soul together – for us, if not for our books.

Copyright law did a pretty good job protecting books from piracy for exactly three centuries. But the technological developments of the last few years are rapidly transforming both books and piracy, and have greatly reduced the practical effect of copyright in books. The law of copyright is as crucial as ever in defining authors’ rights and providing the framework for authors, publishers, and distributors to deal with each other. But it can only be enforced in jurisdictions that play by the rules.

Every year, the International Intellectual Property Alliance publishes a Priority Watch List of countries where intellectual property is inadequately protected as a matter of law or enforcement. In 2012 it singled out Pakistan, Russia, Brazil, and Vietnam as problem areas for book piracy. The Internet is a rogue nation vaster and more lawless than all of them together. We cannot threaten it with trade sanctions or haul it in front of any tribunal. We cannot win a war against it, any more than St Finian could. But we can hang out our own shingle there, we can compete with the pirates head to head. Our product is better than theirs. We can’t beat them on price, but we can still beat them on value for money. We just have to be smart, and flexible, and brave.

.jpg)