- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Music

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Rather like a consummate storyteller, Mozart knows how to keep us close to the edge of our seats,’ says Andrew Ford, composer, broadcaster, andauthor of this collection of illuminating essays on musical themes assembled from his talks, articles, and scripts for the radio series Music and Fashion. Like Mozart, two of Ford’s strengths are his compelling voice and his capacity to keep the reader enthralled. The down-to-earth title signposts something different, something digestible and fun to read.

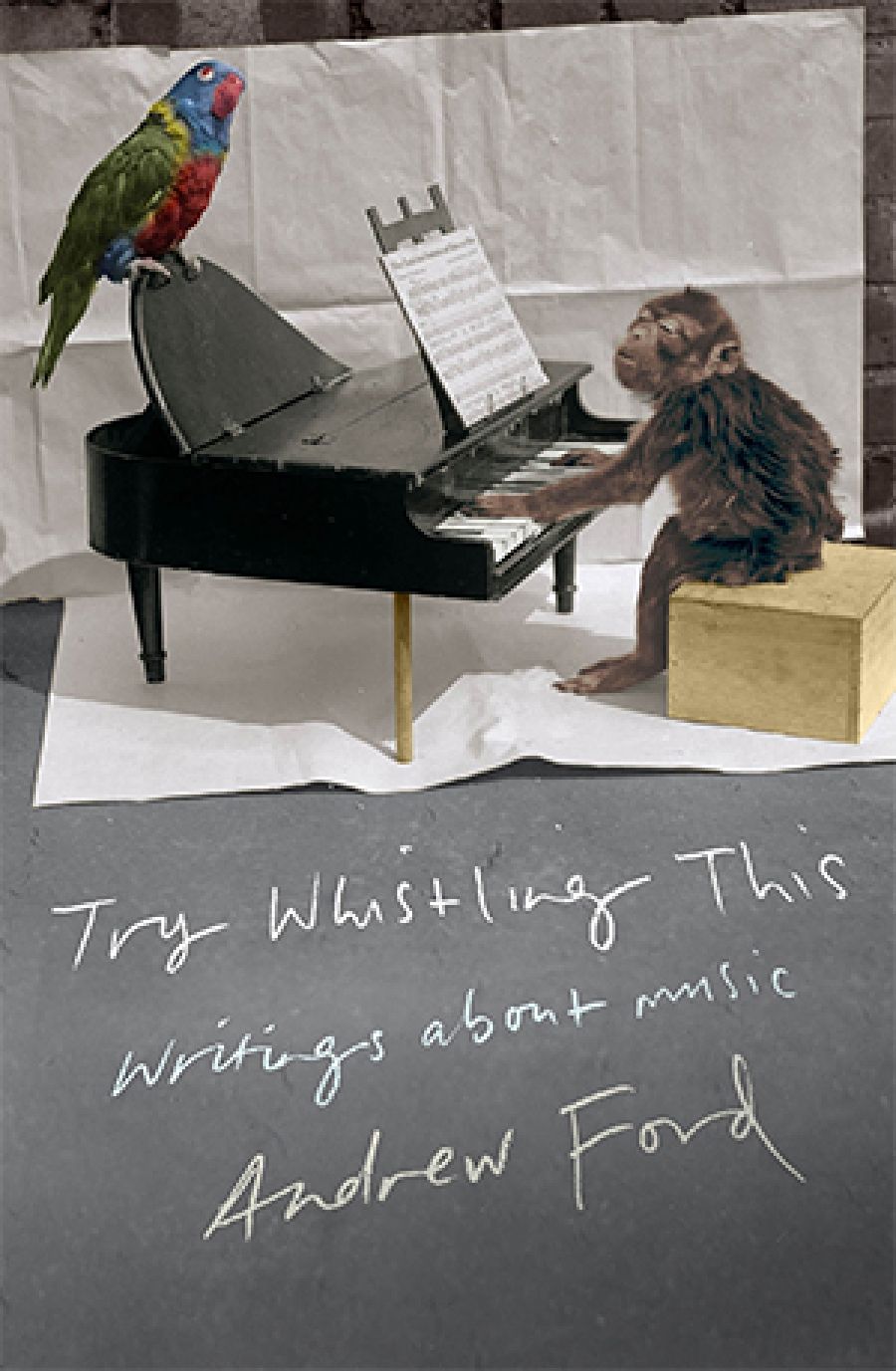

- Book 1 Title: Try Whistling This

- Book 1 Subtitle: Writings about Music

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $32.99 pb, 343 pp

William Walton, Peter Maxwell-Davies, and Beethoven are portrayed as vulnerable, ordinary souls, rendered interesting by the fact that their vocation is composing rather than accountancy or piloting jumbo jets. As a composer himself, Ford identifies with many of his subjects. In Stephen Sondheim’s words, he knows how to ‘make a hat, where there never was a hat’. Handel wasn’t a musical god, suggests Ford; instead, he made music to earn a living and demonstrated as much flair in dreaming up populist hooks as did Andrew Lloyd-Webber. For the entrepreneurial creator of The Messiah, it wasn’t Eva Perón or The Phantom of the Opera, but the concept of watery music that gladdened eighteenth-century ears. If Handel’s offerings, unlike Lloyd-Webber’s, happen to fall within the bailiwick of ‘great art’, so much the better, but chasing income was the motivation. Deifying Mozart and Mendelssohn comes at a price, with lighter pieces originally designed as aural wallpaper ending up awkwardly centre-stage.

The essays about composers sparkle. Ford champions Elgar and Liszt, defends Walton, pens an eloquent eulogy to Richard Meale, muses about Vaughan Williams’s crustiness, explores Brett Dean’s international success, and recommends Mary Finsterer. Scratchy questions come with the territory. Why was Vaughan Williams offended when someone asked him what his latest work was about? After all, he was the one who, rather than attribute organisational numbers to new scores, christened them with saccharine titles like The Lark Ascending or A Pastoral Symphony. The latter conjured a fantasy of the English countryside, making his music an easy target for Elisabeth Lutyens, who mischievously coined Vaughan Williams’s output as the ‘cowpat’ school. Was Shostakovich ‘a musical freedom fighter’ or an arty chattel of Stalin’s Soviet Union, churning out oceans of orchestrally phased propaganda? Were Mahler’s symphonies stamped with Sound of Music foleyesque effects because of his thespian day job as an opera conductor?

It isn’t just the composers who cop gossipy asides. Toscanini was reputedly addicted to giving oral sex. About conducting he said, ‘you can see me suffer – I’m like a woman giving birth.’ Conventions like the recital are recast as gladiatorial spectacles. Seeing Lang Lang scale the treacherous reaches of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier Sonata is edge-of-the-seat reality drama. Will this person make it safely to the other side? In ‘What Makes an Opera Singer?’ Ford scolds both ‘those who believe opera is something to aspire to and those who think it’s a despicable bourgeois conspiracy’. Why? Well, both groups equate opera with a lofty status and thereby curtail its reach.

Ford complains about the possessive branding of composers as Australian. At least the nationalistic stamp reflects a recognition of value, something that does not extend to music critics. Ford is squeamish about being labelled a critic and recoils from judging other people’s music. Yet Ford is as much a music critic as he is a composer; he could almost be the equivalent, although less celebrated due to the parlous status of Australian criticism, of the similarly oriented Alex Ross of New Yorker fame.

Like the American author of The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (2007), Ford writes about Western European art music with a beguiling informality and twinkle-in-the-eye accessibility, the latter being the weapon of choice for both these astute authors. Addressing an inclusive audience of the musically erudite and the culturally curious is mostly accomplished, perhaps slipping only in ‘What to Listen for in Music’, with its condescending wave of an avuncular hand, and ‘Dirty Dancing’, in which Ford sometimes becomes gratuitous.

With Ford’s airing of his childhood in postwar Britain and debate about Furtwängler’s morality in conducting orchestral concerts for the Third Reich, the readership is more likely to be those nudging their fifth, sixth, and seventh decades rather than Generation Y. The subtitle could have been ‘Writings about Classical Music’: of the thirty-four essays, twenty-eight focus on this specific genre. This is fair enough. Would The Monthly’s music critic Robert Forster be expected to examine classical music as well as rock? Yet there are insightful discussions of the risqué genius of Cole Porter and his sexually intrepid ‘Let’s Do It’, plus musings on Keith Jarrett, Bob Dylan, and Hoagy Carmichael.

These essays are predominantly sketches, not symphonies, and a few are skimpy, merely gliding along the surface. Occasionally, Ford’s ideas present as just another spin on well-trodden culture fodder, but there is pleasure to be had in his journalistic savvy for sharing biographical gems, as well as his whimsically remastered wisdom of the academy. The chatty tone, spiked with confessional disclosures, all sharpens that sense of urgency.

CONTENTS: SEPTEMBER 2012

Comments powered by CComment