- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

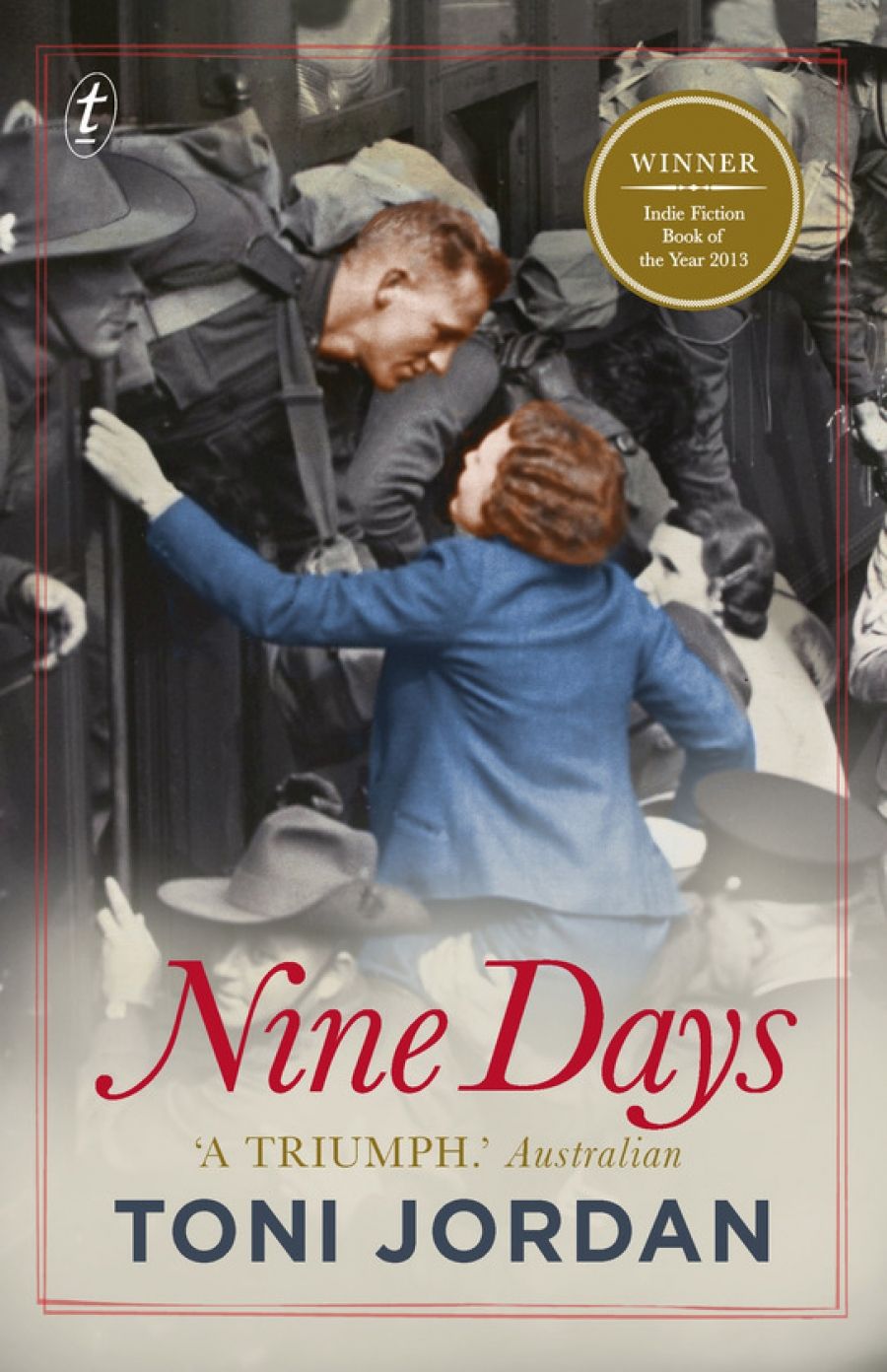

Toni Jordan’s third novel, after the successful Addition (2009), takes its story from a photograph that graces the cover and that the author tells us she pondered for a long time. It is a romantic wartime scene, a crush of bodies at a Melbourne train station, mostly with soldiers bound for their unknown futures. A woman has been lifted by a stranger on the platform so she can farewell her sweetheart. Jordan tells us the story came to her unexpectedly: ‘grand and sweeping, but also intimate and fragile.’ From this one image nine characters emerge whose lives are interconnected and whose voices will be heard individually in the ensuing nine chapters.

- Book 1 Title: Nine Days

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $29.99 pb, 247 pp, 9781921922831

The first of these is fourteen-year-old Kip Westaway, from his Richmond home in pre-war Melbourne. Jordan is adroit at conveying place and class. The reader is taken back to a time when the suburb was quintessentially working class: lanes, smells, specialty stores, pubs, menacing boy gangs, and living ‘halfway up the hill’ sufficient to celebrate that you are not ‘in the gutter’. Kip is streetwise and curious, but cannot fulfil his scholarship at the Catholic St Kevin’s, having been destabilised by his father’s recent death. Kip is happier away from school, being useful as a stable hand to the kindly Mr Husting next door. He gets into trouble without even trying. It is hard not to like Kip.

Ma, Connie, and Francis – Kip’s other family members – relate their own day in three separate chapters that link the story. Francis, Kip’s older twin by a few minutes, continues with his scholarship, ‘shouldering his responsibility’ and getting fried bacon for breakfast, while Kip, known as the ‘chief layabout and squanderer of opportunities in all of Richmond’, has bread and dripping. The loss of their husband and father, the pre-war tensions and restrictions, and the social mores of the times force each of the Westaways into obligations without alternatives. Ma finds work as a cleaner, the family takes in a boarder, and Connie leaves arts school to manage the domestic duties.

Compare this to the modern lives of twin sisters Stanzi and Charlotte, Kip’s future daughters, and Alec, Charlotte’s son, whose stories are interspersed among those of the previous generation’s, and you have a markedly different social imperative. Stanzi is a pragmatic, no-nonsense counsellor, but also fragile, and finds comfort from her neuroses in junk food, while the idealistic Charlotte divides her time as a yoga instructor and part-time health food retailer and has a tendency to cry over the injustices of the world. Alec is the future, and unlike his grandfather Kip, he has a plethora of possibilities ahead of him. Still, he complains: ‘this waiting for my life to start, it’s driving me mental.’

The contemporary characters, living in the post-9/11 and pre-Iraq War world, are much less compelling. Perhaps this is the author’s intention. What she reveals with her characters is their feelings of futility in a chaotic world, their obsessions, insensitivities, over-sensitivities, and selfish preoccupations while trying to make a difference. Charlotte puts it bluntly: ‘All this time and I’ve done nothing. I’ve achieved nothing. I’ve been running down the years of my life … doing a million inconsequential things.’ Why do the characters of the past appear just as flawed, yet somehow heroic? Do we romanticise the past and forget that we are living it for future generations?

Despite the serious overtones, this is an easy book to read, with many observations about families and their foibles, comic scenarios involving objects and underwear, sharp repartee between mothers and sons, twin siblings, and neighbourhood louts. Kip’s capacity for verbal sparring with the local bullies is a highlight: ‘I see the elocution lessons are paying off, Cray … Any day now you’ll come out with a full sentence.’

Jordan sets up tantalising scenarios for many of her characters, placing them in situations where their desires are overshadowed by their reason, where their decisions equate to serious and life-altering outcomes, to happiness, tragedy, a life lacking lustre. In some ways it is a morality tale, valuing the modest, the honest, and the good, but equally forgiving of the misguided, the vulnerable, and the damaged.

Each period presents the complexities and demands of the era in question. Each is as valid as the other, where social obligation is restraining on the one hand (‘The shame that comes from behaving in ways you oughtn’t’) and personal freedom to choose the life you want is just as limiting on the other (Stanzi on her clients: ‘They cannot keep the anger in, these women: they drink too much, they shoplift, they sleep with their doubles partners, they scream at their children, they pay someone to take a knife to their eyes or breasts or stomachs’).

Jordan is clear that what binds us to one another and to a meaningful life is simply valuing the life you have been given and the family that is yours and yours alone. Reading Nine Days, you will laugh, even cry, but you will be in no doubt that Toni Jordan uses the modern novel to reflect those tensions that exist for many of us between duty and desire.

Comments powered by CComment