- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Few would suggest that global capitalism is in rude, unqualified, health. Greece has just voted on whether to stay in the Euro, global markets continue their rollercoaster trajectory, and millions of workers in advanced Western economies remain jobless. With much of the rich world halfway into a lost decade, capitalism is suffering another of the periodic and devastating crises that seem an ineradicable aspect of its nature.

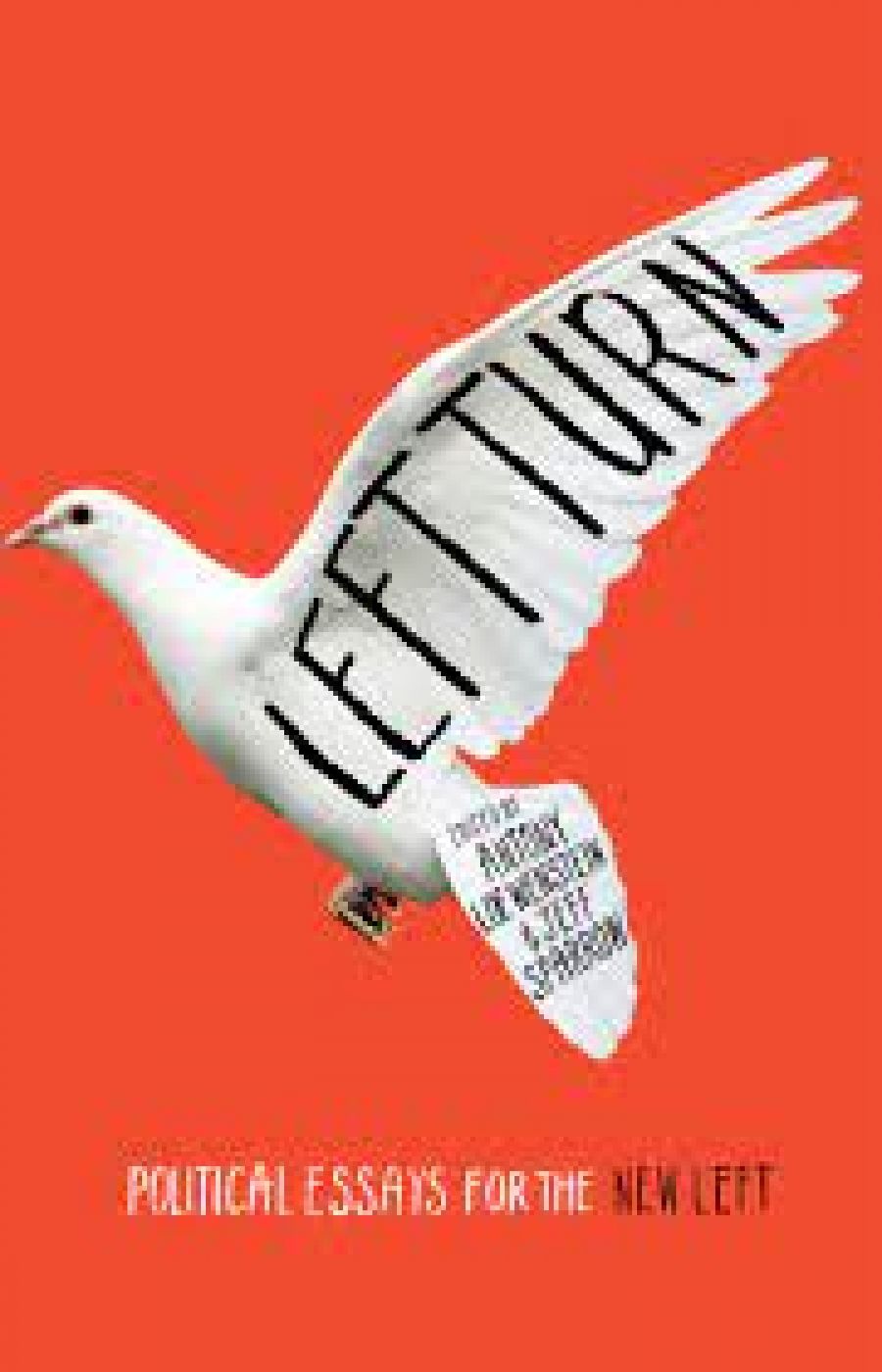

- Book 1 Title: Left Turn: Political Essays for the New Left

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $27.99 pb, 279 pp, 9780522861433

Tsiolkas’s ‘The Toxicity of Smugness’ is shot through with the painful intellectual honesty that often haunts the characters in his fiction. In many ways it is pure polemic, a moral essay in the tradition of Swift or Rousseau. Tsiolkas makes the acute observation that organised labour in Australia became detached from the environmental movement, and that, moreover, the Greens and much of the so-called ‘progressive’ opinion they represent are comprehensively bourgeois. As a result, progressives make little attempt to engage with the aspirations and experiences of working-class people, especially when they hold socially conservative views, instead writing them off as ‘bogans’ or ‘rednecks’. There is a smugness to left-leaning politics in Australia that Tsiolkas finds intolerable.

Tad Tietze and Elizabeth Humphrys’s essay on the politics of climate change is also valuable. They make the simple but compelling point that market capitalism can’t address the looming disaster of global warming. Indeed, given that the entire architecture of ‘cap-and-trade’ policies proceeds from the starting point of a regulatory cap on emissions, it should be obvious that only government regulation can address the problem that Nicholas Stern called the ‘greatest market failure the world has ever seen’. Indeed, Tietze and Humphrys think that one reason why carbon pricing is so unpopular is that it is essentially a neo-liberal solution to the problem; unless addressing climate change is ‘seen as a collective social task rather than one for disembodied ‘markets’, climate action will run a distant second to the drive for profit’, they conclude.

Other essays in this collection are less praiseworthy. Tom Bramble argues, unpersuasively, that strikes are the answer to declining levels of union membership. Rick Kuhn mounts a full-frontal assault on Keynesian social democracy, but advances only an insubstantial and declamatory vision of neo-Marxism in response. Emily Howie pursues a human rights-based approach to social change, coupled to the monitory democracy of non-government organisations such as Human Rights Watch. But she ends her essay weakly, admitting that ‘ultimately we are at the mercy of the political cycle’.

A number of problems bedevil all the contributions here, and political critiques of capitalism generally. One conundrum is the state and its role in the economy. For leftists, the state is a fundamentally ambiguous actor: the only feasible institution capable of mitigating the excesses of capitalism, safeguarding human rights, or saving the world from climate change, it is also an agent of oppression; in the case of China, the state combines ruthless political repression with pro-market zeal.

Another problem is political agency. Should capitalism be fought at the ballot box, by citizens voting in elections? If so, the positions espoused by the contributors in this book, most of them to the left of the Greens in policy terms, would currently enjoy little electoral support. Should the battle then be fought in the streets, with Occupy-style protests? In the media, by NGOs and independent journalists? In broad-based social movements, by activists and campaigners? In the workplace, by unions? In courts, by lawyers?

All of these tactics are suggested in various chapters of Left Turn, a measure of the contested status of the problem and the nebulous nature of the goal. No one, not even Rundle, can advance a coherent alternative vision for the organisation of our economy and society. As Tietze and Humphrys acknowledge, ‘the problem is too big for anyone on the Left to pretend they have a ready-made formula to peddle’.

Comments powered by CComment