- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Percy Grainger has been the subject of a number of books (most notably a 1976 biography by John Bird), a play (A Whip Around for Percy Grainger, 1982) by Thérèse Radic, and a feature film, Passion (1999), by Peter Duncan. He was an avid letter-writer, and his correspondence has been anthologised and critiqued. Thanks to his eccentric way of life and sometimes erratic behaviour and opinions – his famously close relationship with his mother, Rose, his self-flagellation, dubious theories of race and culture – the composer has also long been the subject of salaciousspeculation. Grainger was a large personality, and conjecture about his habits and personal tastes has often over-whelmed considerations of his modest, yet important, output as a composer and arranger.

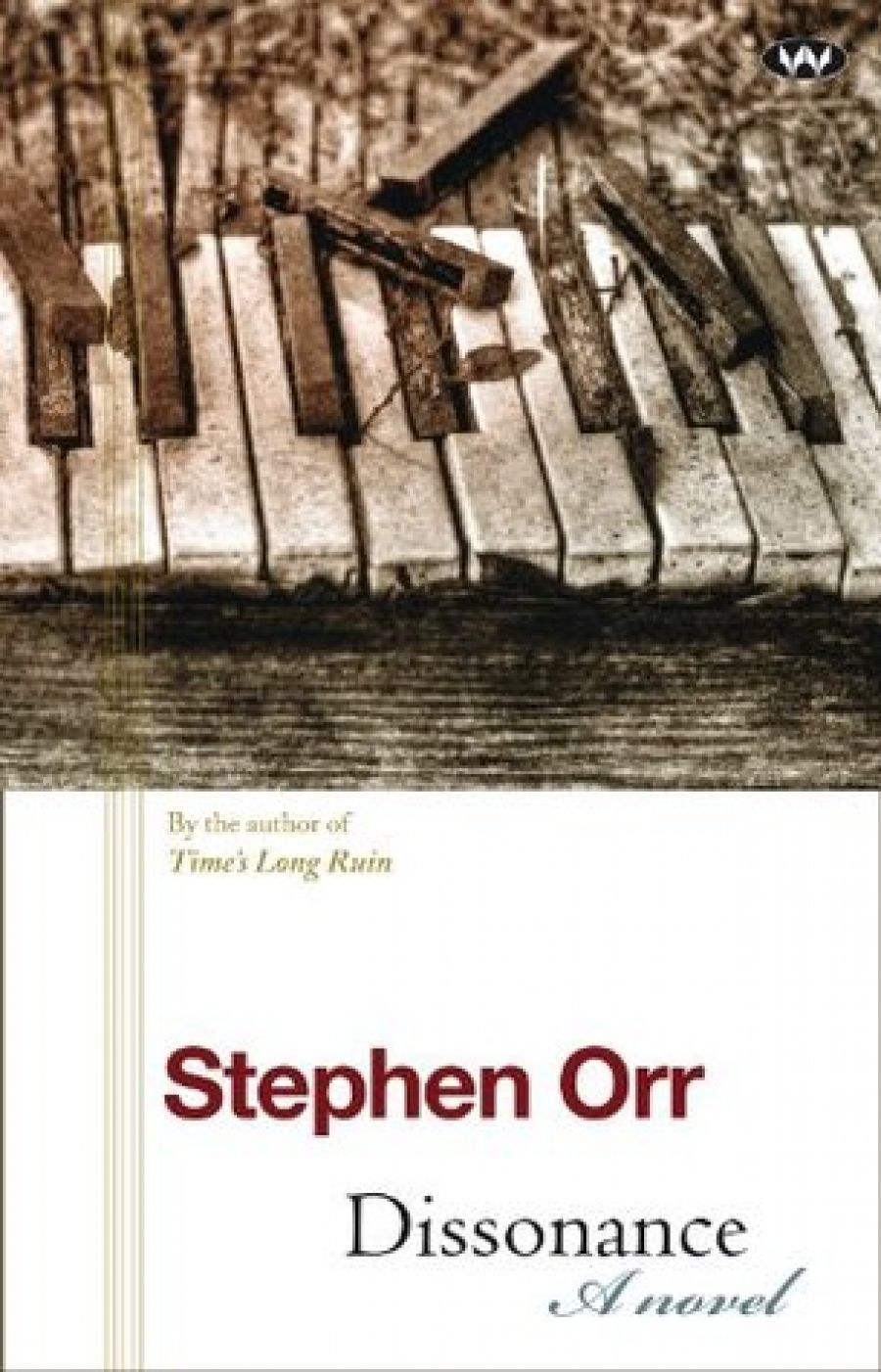

- Book 1 Title: Dissonance: A Novel

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $27.95 pb, 408 pp, 9781862549456

Stephen Orr has taken some of the main themes and impulses evident in Grainger’s early years, and in Dissonance, his fourth novel, made of them a compelling fiction of a young man propelled towards musical renown by his ambitious, manipulative, ever-attentive mother. Erwin Hergert, ‘a good-looking fifteen-year-old with wavy hair, a high forehead and square jaw’, is a prodigiously talented pianist who lives in Tanunda, in the Barossa Valley, with his mother, Madge, and father, Johann. Johann’s family are among the many ‘Barossa Germans, with their belief [according to Madge] that music was all oom-pah and close harmonies’, which Madge helps her gifted son ‘overcome’, along with overcoming ‘schools full of second-rate teachers, religion, and most of all, Johann’. Compromise, the ‘second rate’, ‘the path to mediocrity’, are constant obstacles in Madge’s life. Struggling financially, and socially on the middle rung at best, she is almost maniacally determined to raise Erwin – and, by intimate association, herself – above the also-rans. Erwin’s piano is the vehicle driving this ambition. Nothing short of international fame will suffice.

For reasons that only become fully clear later in the novel, Madge has banished the unfortunate, if unfaithful, Johann to the shed. (The image of the shed recurs throughout the novel as an emblem of banishment and refuge.) Inside their stone house on God’s Hill Road, Madge counts time ‘in a clear, metallic monotone more precise than any metronome, tapping an arthritic bamboo stick on the lid of their old iron-framed piano’, at which Erwin practises six hours a day. Lapses in discipline see Madge producing a whip.

Dissonance is broken into four parts, each aligned to a different period or setting. Scenes in the opening chapters are snatched from various points early in, or sometimes pre-dating, Erwin’s life. Such is the effect that it is occasionally difficult to identify a discernible ‘present’, but Orr’s technique skilfully builds a picture of complicated familial and social relationships that only gradually comes into focus.

Among the complications, we learn that Erwin has a half-brother. Declan is the result of one of Johann’s infidelities. He resembles Erwin and leads a parallel but alternative life, working at his father’s shop and a series of ordinary jobs. Declan’s mother’s warmth is the antithesis of Madge’s control and ambition. Erwin, in turn, leads a kind of parallel life to Grainger. Orr has done far more than simply change names and insert imagined conversations between known facts about the composer’s life. In a nice metafictional touch, Grainger is sometimes cited as a template for the possibilities that lie before the young Erwin. ‘You wouldn’t see Grainger doing that,’ Erwin’s teacher Reg Carter chastises at one point.

More significantly, Orr has brought forward Erwin’s birth forty years, compared to Grainger’s. Whereas the thirteen-year-old Grainger left Melbourne to study in Frankfurt in 1895, the fifteen-year-old Erwin leaves the Barossa Valley in 1937, accompanied by Madge, to study in Hamburg. The effect is to bring the expectations and realities of life in Germany into sharper contrast than they might have been, and to foreground the brutal consequences of anti-Semitism.

The cultural superiority that Madge had imagined of Germany is rarely in evidence. Erwin’s piano teacher, Schaedel, offers sensitive instruction, but has wandering hands. His composition teacher, Knorr, is dogmatic in method and quickly outshone by his brilliant new charge. More generally, demonstrations of superiority often don the garb of a virulent national socialism that, in time, even Madge despises. This leads to interesting character developments and disturbing but finely crafted scenes. When an elderly Jewish man is set upon by a group of soldiers for the most trifling and unproven offence, it is Madge who comes to his aid – this despite her own explicit anti-Semitism back in the Barossa. The dogmatism of Knorr takes on a far more sympathetic complexion when he defends the legacy of now-blacklisted Jewish composers – Mendelssohn and Schoenberg are among the targets.

By contrast, Erwin’s new-found love interest, and later wife, Luise, an otherwise sympathetic character who suffers under Madge’s ‘rule’, readily adopts anti-Semitic cant. Erwin, meanwhile, remains ambivalent. Like an Olympic athlete clinging to the belief that politics has no domain in sport, he buries himself in music for as long as possible, while militarism overtakes Germany and war engulfs the world.

This is an intelligent, beautifully wrought novel. Its finely nuanced characters intrigue and move because of the complexity of their motivations and identities. Its interest lies as much in the domineering, yet ultimately vulnerable, Madge as it does in Erwin. Despite her own superficial characterisations of people and culture, as circumstances change Madge variously describes herself as a German, an Australian, and a Jew. ‘I didn’t know we were Jewish,’ Erwin says at one such point. ‘I can be what I need to be,’ replies Madge.

Comments powered by CComment