- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Every migrant has a story. The past two decades have given us accounts of migration to Australia from so many Asian countries, and from so many viewpoints – sad, painful, funny, cynical, mystical – that little more seems left to tell. But now, out of Africa, comes a writer with a new and altogether more terrible tale.

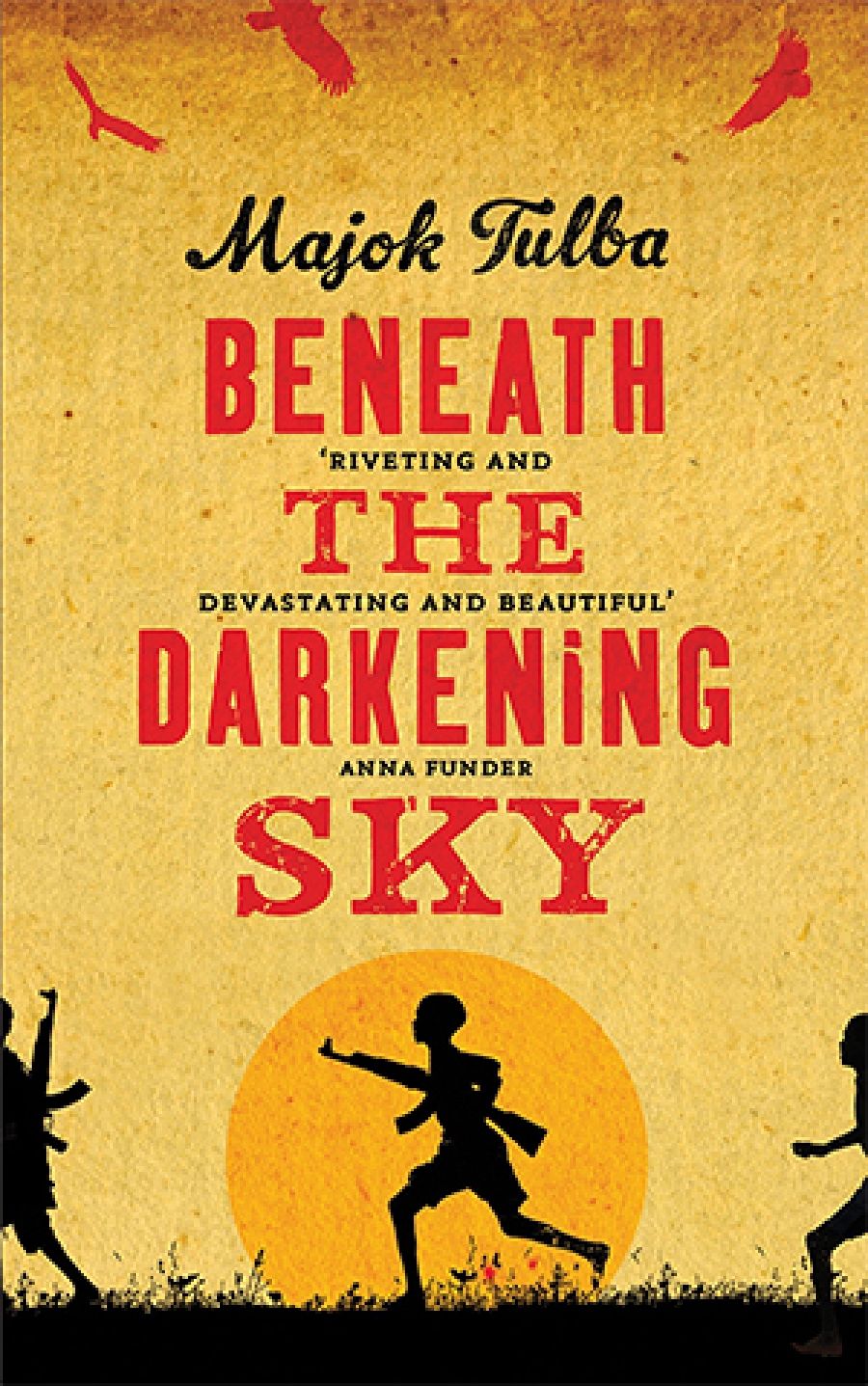

- Book 1 Title: Beneath the Darkening Sky

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $29.95 pb, 239 pp, 9781926428420

Majok Tulba survived civil conflict in South Sudan and was a teenager when he reached Australia in 2001. Tulba had never seen a movie, but he decided to become a film-maker and enrolled in film school with help from a Catholic support group. He supplemented his income by modelling, badly needing the funds, since the Sudanese woman he wanted to marry was going to cost more than 350 cows. Success crowned his efforts, and he now has a wife and three sons in Sydney, and is currently at work on his second novel.

Serendipity to match Tulba’s experience is not in prospect for his hero, nine-year-old Obinna. Like Tulba, Obinna witnesses an armed attack on his village that leaves some of his family dead. His older brother is recruited by Sudanese rebels who command an army of children, turning the boys into soldiers and making the girls provide ‘hospitality’. Obinna is caught, measured against an AK47, and deemed tall enough to join other weeping, homesick boy soldiers. In real life, Tulba himself was just too short, and escaped to refugee camps on the border between Sudan and Uganda.

Telling his appalling story in simple, staccato sentences, Obinna almost makes light of his years of misery, pain, and degradation at the hands of the rebel army, skipping many joyless months as he grows from childhood to adolescence. Being delirious or unconscious is a relief, at least, from beatings, humiliation, and the constant danger of being shot by the idiotic, trigger-happy rebel officers. He dreams of his village, his Mama, his Sunday school girlfriend Pila, and of becoming a doctor. Obinna wonders who was right: his village priest who taught the flock to forgive their enemies, or the gods his grandparents prayed to, who punished bad deeds and rewarded good ones.

Maybe Grandpa’s gods are real. Maybe I made one of them angry and that’s why I am here. Maybe Jesus is angry with me and that’s why I’m here. If that’s why I am here, then God must be angry with the entire country. He must be furious with all of Africa.

Some pages of Obinna’s story are so horrible that reading them gave me the same hands-over-eyes reaction that I have to violent movies. In spite of what the leaders have done to him, he learns to sing their obscene revolutionary marching songs, watches them castrate his elder brother, and, fearing for his own survival, begins to kill on command. Obinna even joins raids to kill villagers and round up children, just as was done to him. He learns from one relatively humane rebel, a Bible-reading man nicknamed Priest, that killing with one shot to the head is merciful, and tells himself, ‘At this range, it’s nothing. One shot and the pain and fear end. An empty body collapses to the ground.’

Obinna’s father was famous as the greatest warrior of his generation, a hunter who could bring down a buffalo with just one spear, or fight a lion with his bare hands. What changes everything for Obinna’s generation is the arrival in Sudan of Kalashnikovs, which give men unprecedented capacity to wield power and to kill at the slightest provocation. They do not appear even to know what they are fighting for or whom they should kill. They love nothing but their guns, and treat them as phallic objects. Obinna’s AK47 is called Crazy Bitch.

A slow smile creeps onto my face, it’s nice to be cheered. Bang. Bang. Bang. I pull my trigger and people die … The only sane thing to do is laugh. So I do. And the way bullets make people’s bodies jump around, like they’re dancing, actually is kind of funny. I make them dance, and I make them die.

Tulba must live with his memories.Some of them are worse – he told Alice Pung in an interview – than what he has written, because he felt Western readers would be appalled. It is hard to imagine what could follow this extraordinary first novel, but he comes from an oral storytelling tradition, and clearly has more than one book in him. The next may continue to lessen our ignorance about his homeland. It is a natural reaction, perhaps, to conclude that sub-Saharan Africa – where the Lord’s Resistance Army has for years made child soldiers commit unspeakable atrocities – cultivates subhuman behaviour. But ruthless cult leaders and religious men prey on children in Western countries too, and young mass killers can be of any nationality.

In Australia, most daily news bulletins bring tidings of another shooting of someone in his or her home. Elsewhere, one death occurs through armed violence every minute. Yet in July a United Nations treaty controlling global sales of conventional weapons was thwarted by some of the biggest arms exporters. Now that Tulba is an Australian, he must be pleased that Australia, at least, is among the co-sponsoring countries of the treaty.

Comments powered by CComment