- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Fighting to the Finish does not get off to a good start; its title is overstated. The First Australian Task Force (1ATF), trimmed down in 1970 from three to two battalions, withdrew from the Vietnam War by December 1971. The small remaining advisory group withdrew in December 1972. Fighting finished in April 1975, when more than 180 battalions of the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) swarmed around Saigon, causing it to fall. It hardly seems sensible to declare that the Australian Army fought to the finish over two years before the end of the war.

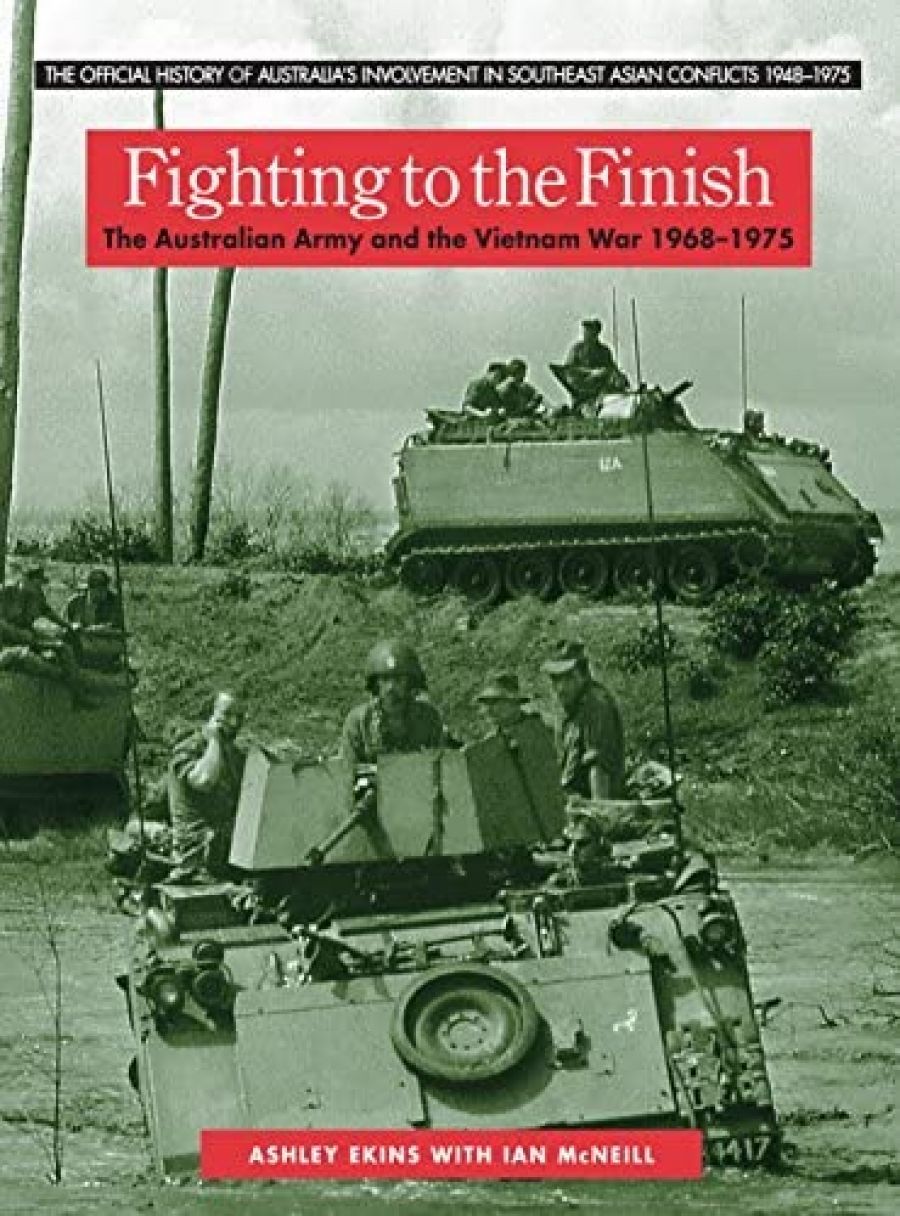

- Book 1 Title: Fighting to the Finish

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Australian Army and the Vietnam War 1968–1975

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $100 hb, 1139 pp

How can the title of a work that has been some ten years in the making fall short so conspicuously? The answer is, I think, the political pull of the Anzac canon. C.E.W. Bean’s seminal Anzac opus, The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–18 (twelve volumes, 1921–42), raised the issue of whether the Anzac Corps, which had played a continuous, spearhead role in the offensive on the Hindenburg Outpost Line in 1918, would be rested or fight on in what would be the final push on the Line. Two divisions of the Corps did fight to the finish. No matter how historically unsuitable that point of reference may be, Ashley Ekins has now used it to incorporate his account of the Australian Army’s last years in Vietnam into the Anzac expeditionary tradition.

The misnomer does not necessarily undermine the Official History’s important political and social function: recognition of soldiers’ deeds. Fighting to the Finish is an Anzac memorial volume. Recording everything he can, including medical civil affairs and training matters, Ekins convincingly captures the long grind of infantry patrolling, broken occasionally by thirty-second contacts and horrendous mine casualties. His most gripping passages describe sustained contacts, when, even more occasionally, silent patrolling erupted into protracted skirmishes and bunker battles involving tanks and artillery. Take a tank attack on 21 June 1971. An enemy rocket propelled grenade (RPG) hit the left flank tank, commanded by Corporal A.M. Anderson:

The projectile struck the commander’s .30 calibre machine-gun and detonated severing Anderson’s left arm and also wounding him in the head. Shrapnel also badly wounded the [radio] operator, Trooper Phillip Barwick, in the chest and head blinding him temporarily … A second RPG exploded in the trees alongside the vehicle. Other tanks immediately returned fire. Second Lieutenant Bruce Cameron … fired canister rounds … silencing the enemy. Meanwhile, [a nearby infantryman] New Zealand Lance Corporal John Adams, displayed outstanding bravery … Disregarding the intense enemy fire, he mounted the tank to direct the rescue and encouraged the wounded men … Adams was awarded a Military Medal.

Heat and horror enliven the narrative. Other stories convey similar intensity, including those of Cameron’s heroic feats, for which he was awarded a Military Cross. Optimally, Fighting to the Finish contains a series of linked citations for shared madness and glory.

Nonetheless, the volume does not present a coherent history of the war. The proposed ‘pattern’ of 1ATF operations is given no meaningful political or military context. In mid-1968 we first meet 1ATF fighting against the regular main force units of the ‘North Vietnamese Army (NVA)’ in and around remote parts of Phuoc Tuy Province. Then there was ‘the other war’ in and around the villages, where the Saigon government’s authority had disintegrated as a result of terror and small-scale guerrilla action orchestrated by the ‘Viet Cong (VC)’ – Vietnamese communists. Overall, 1ATF alternates between the two wars, and its operations take many forms. But even if this construction accommodates a 1ATF conception of what it was doing, it misses the big picture. It ignores the independent thrust of Vietnam’s thirty-year war for national liberation against the French and Americans and that war’s setting within the irreversible, Asia-wide process of decolonisation, post-1945.

Late in Chapter 17, the book’s two-tiered conclusion undermines itself: 1ATF ‘had helped produce a level of security and [Saigon] government control … But the underground Viet Cong infrastructure remained intact, its popular support deeply rooted in the social fabric of village life.’ The second sentence subverts the first; it also casts doubt on itself. How could an infrastructure be ‘underground’ if it had strong ‘popular support’ in the social fabric? The answer is only from a 1ATF perspective, not one from within the villages. The author does not comprehend his own conclusion: 1ATF could never have created meaningful, long-term security in the villages when it could not relate to what was going on in them.

Failure to grasp this fundamental problem also seriously weakens the book’s explanation for the 1ATF minefield disaster. In 1967 1ATF Commander Brigadier Stuart Graham laid a minefield containing some 20,000 lethal M16 landmines around Dat Do village. He thought that obstacle would protect the villagers from the ‘NVA’ main force units. But local guerrilla forces entered the minefield, lifted thousands of mines and turned them back against 1ATF, killing and mutilating more than 300 Australian and a further 200 Allied soldiers. To help account for this tragedy, Ekins quotes another commander as saying Graham’s minefield concept was ‘sound’, the problem being that the friendly Vietnamese (and Australian) forces he thought would guard the field did not do so. But Ekins might have made more than a passing reference to the technical detail that there were not enough troops in the province to guard a minefield of the size that Graham laid in the first place. Ekins also remains silent about Graham’s primary problem: Graham did not understand that the Dat Do villagers he was trying to protect were his enemy; that those villagers would be involved in lifting the mines.

The last Australian troops leave Nui Dat on 7 November 1971 after handing control of the former Australian task force base to the South Vietnamese Army (AWM Neg. No. P07256.006)

The last Australian troops leave Nui Dat on 7 November 1971 after handing control of the former Australian task force base to the South Vietnamese Army (AWM Neg. No. P07256.006)

Why that silence? As his inapposite Anzac title foreshadows, Ekins is still unable to clarify the Australian Army’s enemy in Vietnam. As indicated, the terms he almost invariably uses to describe them are ‘North Vietnamese Army (NVA)’ and ‘Viet Cong (VC)’. These terms have long been in common use, as his Glossary emphasises. But, while the common usage could be real, the Glossary’s stress on it is spurious: Australia’s enemies never formally referred to themselves in those terms. Indeed, the Vietnamese provincial histories that Ekins has read in English translation and quotes several times do not use, in the Vietnamese originals, equivalents for NVA or VC.

There are reasons for this. No state of ‘North Vietnam’, and thus no NVA, ever existed. The army that supported the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the northern, central, and southern parts of the country from 1945 and unified it in 1975 was the People’s Army of Vietnam. Meanwhile, anarchists, Buddhists, religious sects, and landless peasants as well as communists supported the southern insurrection against the US-backed Republic of Vietnam’s Saigon government. The front that emerged under Hanoi’s direction in 1960 was far too complex to be described accurately as ‘VC’. It was named the ‘National Liberation Front for the Southern Region’ (NLF), with units of its military wing being designated as ‘guerrilla’ units of a particular village or as semi-regular region forces. Australia’s enemies saw themselves fighting for national unity and independence.

Unable to grasp that such a desire for decolonisation drove the winning side, Fighting to the Finish has no integrated argument. Rather, overloaded with opinion, the book reports such a wide variety of views that it seems to say nothing. Remarkably, on its last page, we have the Official History attributing the outcome of the war to the popular appeal of ‘the venerated Ho Chi Minh’. This outlook is even supported by criticism of the Americans for undermining the legitimacy of the Saigon government. But such views are free-floating. They are not derived from the main body of the work. They conflict with the book’s emotional fixation on ‘the communists’.

Fighting to the Finish has no explanatory power. It hedges the truth that the Australian Army was sent to Vietnam in the Anzac expeditionary tradition to encourage and assist the Americans to suppress independent Vietnamese nationalism; that Australians also undermined the legitimacy of the Saigon government; and that, indeed, the people Australian soldiers were told they had been sent to protect in Vietnam were substantially their enemy. 1ATF had no strategic initiative. PAVN main and NLF guerrilla force strategies were politically integrated in the villages such that pressure on one meant a resurgence of the other. 1ATF was tactically proficient. Its troops did what was asked of them. But Australian forces were in a holding pattern in Vietnam, a no-win situation, in which, wisely, they were never ordered to fight to the finish.

Comments powered by CComment