- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Do we choose our own destiny or does fate decide? This existential question is at the heart of Dancing to the Flute, a contemporary fable set amid the banyan trees and frangipani flowers of rural India.

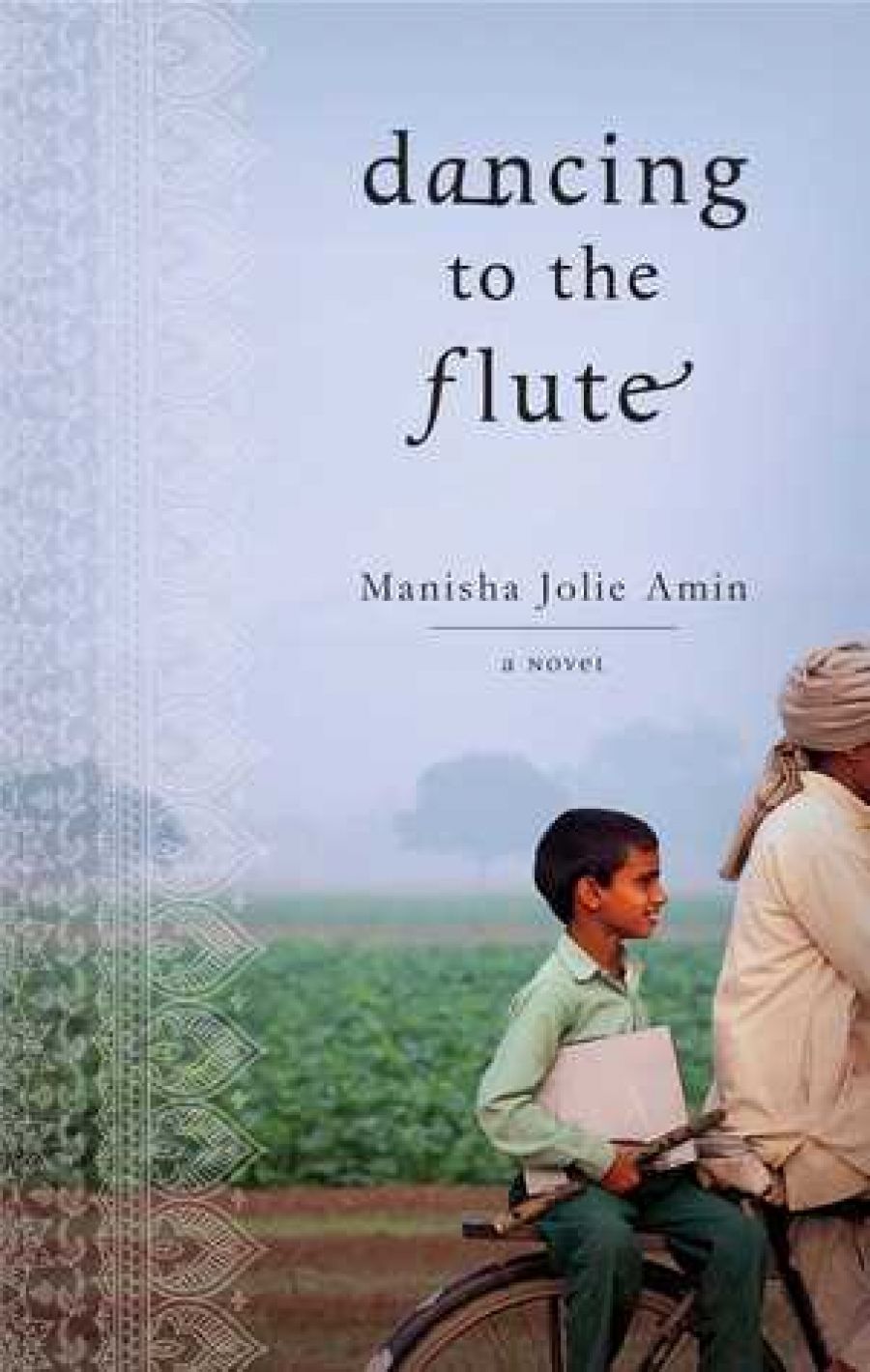

- Book 1 Title: Dancing to the Flute

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin , $29.99 pb, 342 pp, 9781742378572

As the story opens, Kalu is a child with no future, seemingly. He is an orphan, illiterate, and living on the street. Kalu’s only possession is a yellow plastic flute; his only friends are Bal, a buffalo herder enslaved to his master, and Malti, a servant girl indentured to Ganga Ba, her wealthy but benevolent mistress. Can Kalu, this child with nothing, become a true citizen of the world through talent, opportunity, and perseverance? Kalu has the talent, evident even without any education or training. The opportunity comes when he goes to live with the great virtuoso Guruji, a famed musician now living a reclusive life in the mountains. Guruji is determined to transform Kalu ‘from a scrubby street urchin into a musician’.

Kalu, Bal, and Malti grow up during Kalu’s long years of training. Kalu learns as much about life as he does about music. As Guruji tells him, ‘you can take your experiences and choose how they change you’.

Sydney writer Manisha Jolie Amin paints an affectionate picture of life in India. This is the romanticised exoticism of someone who clearly loves the land and its people, but hasn’t actually lived the life. These streets are not too squalid, the abuse not too violent. Only the ritualised violence against women reveals India’s dark side. Even this Amin depicts with a gentle touch. Her words enhance the dignity of the women and diminish the perpetrators, but stop short of condemnation. There is an elegant acceptance of cultural truths, no matter how unpalatable they are.

Dancing to the Flute is an accomplished début novel. Vaid Dada, Guruji’s brother, may say ‘this is not Pygmalion’, but the allusion is apposite.

Comments powered by CComment