- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Continuously inhabited since at least the sixth century, Delhi is fabled to be the city that was built seven times and razed to the ground seven times. Some believe the word Delhi comes from dehali or threshold, and the city is seen as the gateway to the Great Indian Gangetic plains. In 1912 the British moved their colonial seat of power from Calcutta to New Delhi, which also became the capital of independent India and celebrates its hundredth anniversary this year. It seems apt, then, in 2012, to read about the older Delhi that lies and lurks behind the shining veneer of India’s National Capital Territory, a Delhi that the rising Asian power seems eager to forget and obliterate.

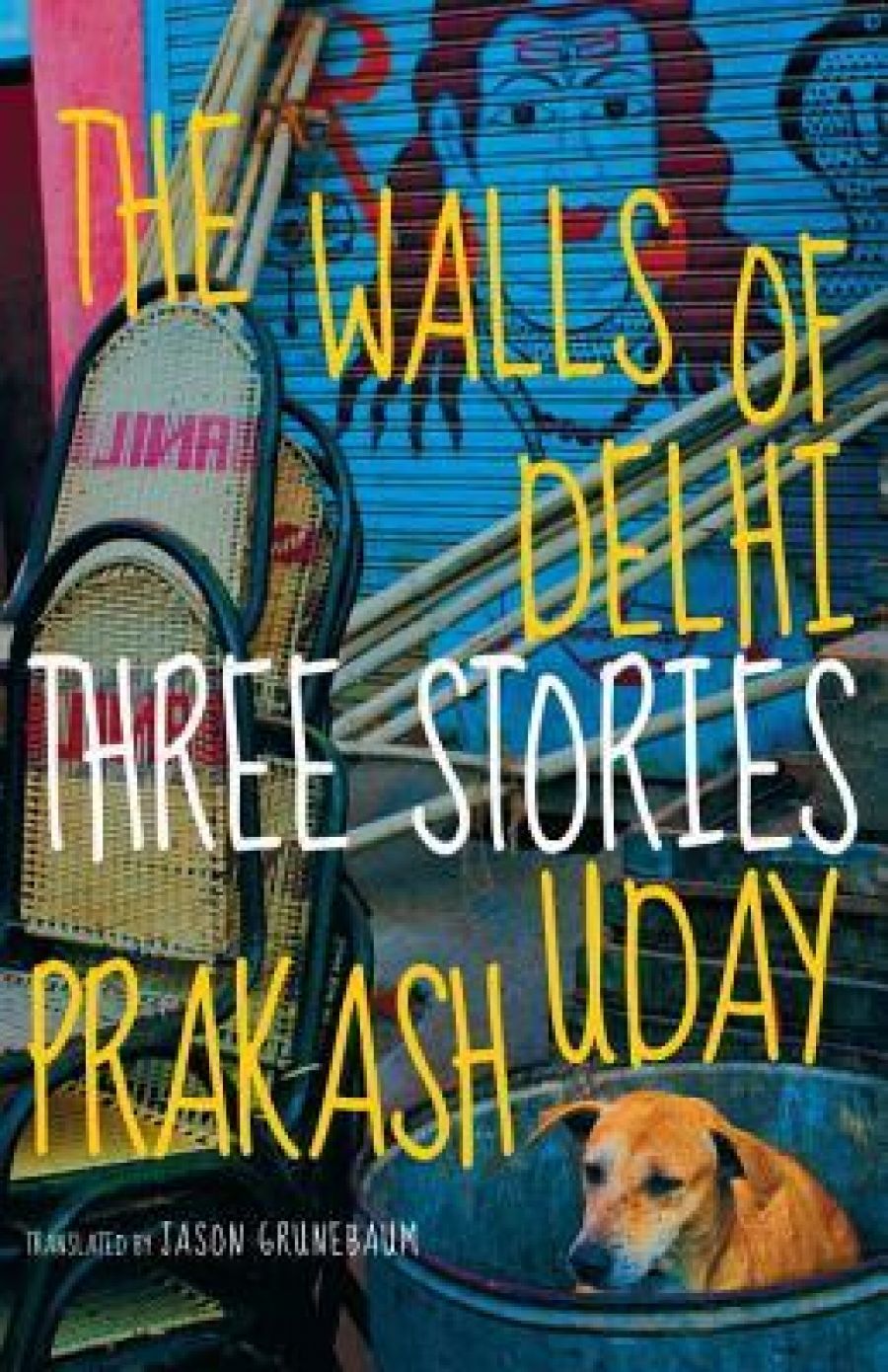

- Book 1 Title: The Walls of Delhi

- Book 1 Biblio: UWA Publishing, $29.95 pb, 227 pp, 9781742583921

Uday Prakash’s The Walls of Delhi, a set of three novellas, translated from the Hindi original by Jason Grunebaum, joins a recent crop of works that evoke the lost splendour and shocking contrasts of Delhi, such as Mahmood Farooqui’s Besieged: Voices from Delhi 1857 (2010), Malvika Singh and Rudrangshu Mukherjee’s New Delhi: Making of a Capital (2009), Sam Miller’s Delhi: Adventures in a Megacity (2009), Ranjana Sengupta’s Delhi Metropolitan (2007), and William Dalrymple’s popular coffee-table tome, City of Djinns (1993). The Walls of Delhi, however, is an exposition of a different kind. The novellas – ‘The Walls of Delhi’, ‘Mohandas’, and ‘Mangosil’ – uncover, as if from under the ubiquitous pothole of an Indian road, the fascinating story of a Delhi separated from its India Rising cousin in all possible ways: historically, geographically, genealogically, linguistically, materially. Anyone who has ever been to India will have flown past these indescribable slums and shanties on the way to glitzier tourist monuments: Prakash’s narratives make real their undeniable, unmistakable coexistence just below the radar of ‘development’.

Three main concerns animate the novellas that were written across a spread of time: all look at how the transition from the twentieth to the twenty-first century brings disastrous consequences for those not treading the triumphant neo-liberal path to progress. Prakash’s narratives trace the trajectory of dispossession that attends the destitute and the detritus of urban lives. ‘The Walls of Delhi’ and its ruined, ramshackle brick enclaves assembled over flowing sewers and stinking drains provide the necessary shelter to all those migrants who arrive in the metropolis escaping lives worse than death elsewhere. Here they make a living cleaning the houses of those on the rung just above them, driving powerful people to important jobs, maintaining equipment at gyms for people who have enough to eat and want to shed weight. Amid this, the Mohandases of the world eke out a hardscrabble existence, bring up children with mysterious diseases like Mangosil, and make a claim to humanity.

The second concern in these novellas is about the role of literature in narrating such lives, especially the role of the writer in Hindi literature. Using the standard language of Northern India, Hindi literature enjoyed its heyday from the 1950s to the 1970s. Prakash traces his lineage to stalwarts like Premchand, Phanishwar Nath Renu, and Muktibodh, who used the social-realist mode to tell their stories of emerging India. What would have been the social realism of an earlier era, however, has become the surreal in our times: descriptions are preposterous enough to defy belief, and yet are part and parcel of unprivileged lives everywhere in India today. Prakash’s poignant cry to Hindi literature itself for succour, to art for deliverance, pays homage to Amir Khusrau, the first poet of the language called Hindi, whose shrine remains neglected in the great courts of Hazarat Nizamuddin in old Delhi. Prakash’s diatribes against the contemporary Hindi literary establishment punctuate the novellas and draw a likeness between their disenfranchised characters and their equally penurious narrator–author as the voice of history.

The third thread tying together the three novellas is a chronicling of contemporary world events. Even as Prakash details the crime, the corruption, and the crippling burden of poverty that stands in the name of ‘life’ in modern India, he is cognisant of larger and parallel forces of degradation occurring everywhere on earth. Lest we think that these stories are a throwback to some nineteenth-century nightmare of industrialised squalor and sloth, he asks: ‘as I’m writing these lines, in Karbala, Baghdad, Fallujah, Najaf, Nasiriya or in the Gaza strip – is it so different from what’s happening in Delhi’s Gurgaon, Noida, Silampur, Bhilasava, Rohini, Jiyasarai, Mahrauli?’ Indeed, is it so different from what is happening in Aboriginal communities in Australia? Which is why it is commendable that UWA Publishing has published these remarkable translations that bring across to us some of the milieu and flavour of times, places, and languages that face extinction. What endures is the humour and humanity with which the narratives touch us. Behind the tattered grey makeshift curtains that accord these lives a notional privacy and dignity, we see the fabrics and colours of an irrepressible intelligence and imagination that makes human life what it is.

Comments powered by CComment