- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

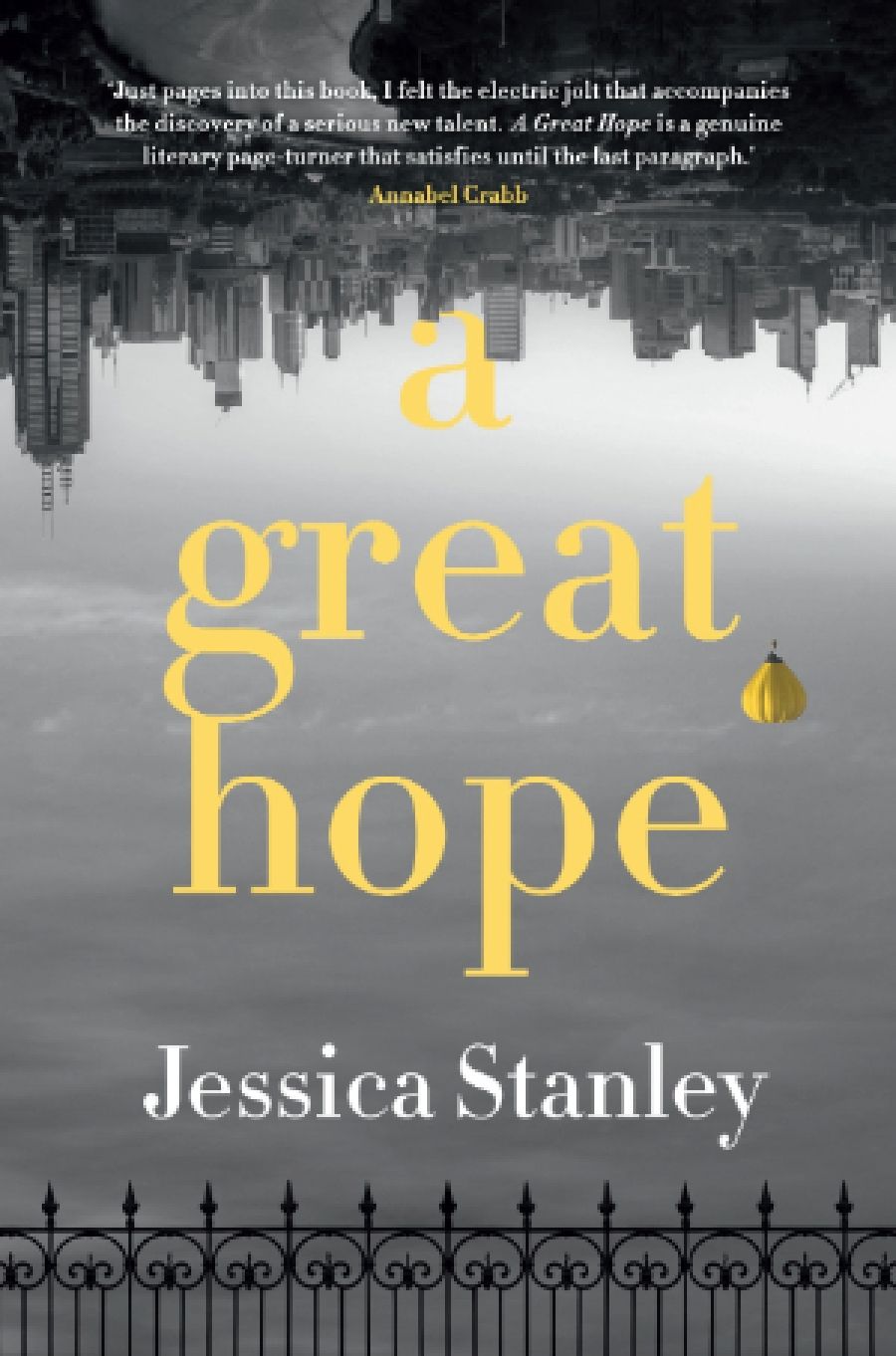

- Custom Article Title: The education minister’s jackboots: Political interference in research funding

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The education minister’s jackboots

- Article Subtitle: Political interference in research funding

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

No one can doubt the combined impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and Australian policy responses to mitigate its effects, over the past few years. While assessing which groups or sectors suffered more than others will only lead to an invidious victimological contest, we can agree that Australia’s thirty-seven public universities took a number of heavy hits after March 2020. In the year to May 2021, senior managers in Australian universities shed 40,000 jobs, most of them casual teachers, and sixty per cent of them were positions held by women. Unsurprisingly, many inside those universities, along with commentators outside, concluded that the federal government’s decision not to offer JobKeeper payments to public universities reflected a deep animus against and fear of universities. Some reflected on the hostility directed towards the ‘cultural Marxists’ who, it is fantasised in some quarters, still exercise their hegemony in these ‘ivory towers’, notwithstanding the fact that the 2019 report by former High Court Justice Robert French definitively scotched allegations about a rampant ‘woke left’ ruthlessly crushing dissident voices in the academy.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

No one can doubt the combined impact of the Covid-19 pandemic and Australian policy responses to mitigate its effects, over the past few years. While assessing which groups or sectors suffered more than others will only lead to an invidious victimological contest, we can agree that Australia’s thirty-seven public universities took a number of heavy hits after March 2020. In the year to May 2021, senior managers in Australian universities shed 40,000 jobs, most of them casual teachers, and sixty per cent of them were positions held by women. Unsurprisingly, many inside those universities, along with commentators outside, concluded that the federal government’s decision not to offer JobKeeper payments to public universities reflected a deep animus against and fear of universities. Some reflected on the hostility directed towards the ‘cultural Marxists’ who, it is fantasised in some quarters, still exercise their hegemony in these ‘ivory towers’, notwithstanding the fact that the 2019 report by former High Court Justice Robert French definitively scotched allegations about a rampant ‘woke left’ ruthlessly crushing dissident voices in the academy.

If disinterested observers had doubts about this hostility towards universities on the part of Scott Morrison’s government, those misgivings were dissipated in an ‘unfortunate gift’ delivered on Christmas Eve 2021. It was a more than difficult year for the thousands of academics who endured the extraordinary and unexplained delay in the annual announcement of successful ‘Discovery Projects’ in the much sought-after Australian Research Council grant applications. With a success strike rate of just nineteen per cent, these awards are competitive as well as prestigious. In the context of cutbacks to university research funding, they can make or break the future of university research centres.

This uncertainty about the ARC results ended when the results were announced on 24 December. As in the two preceding years, that message came with a nasty sting in the tail for some of us.

While 587 Australian Research Grants were funded under the Discovery Program, six grants were vetoed by the acting Education Minister, Stuart Robert. The news sent shockwaves through the academic community in Australia and attracted international comment. We were in a team of seven researchers who learned that our application titled ‘New Possibilities: Student Climate Action and Democratic Renewal’ was ‘Recommended to but not funded by the Minister’. (This has since been removed and replaced by the wording ‘Not Funded’.) Five other teams were likewise subjected to the power of ministerial veto provided for in the Australian Research Council Act 2001. This legislation does give wide powers to the minister even though section 33 (c) of the Act says the minister must not direct the CEO ‘to recommend that a particular proposal should, or should not, be approved as deserving financial assistance’. However, section 52 (4) of the Act states that ‘the Minister may (but is not required to) rely solely on recommendations made by’ the Australian Research Council.

This is an example of extreme political interference in research that is greatly out of step with comparable jurisdictions such as Canada, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Aotearoa New Zealand. However, as we all know, this is part of a longer political pattern in Australia under Coalition governments. The Australian federal government’s interference in what is entirely an independent process overseen by the ARC College of Experts has happened before. In 2006, Minister Brendan Nelson vetoed seven ARC grants. Under Scott Morrison’s government, Simon Birmingham vetoed eleven grants in 2018–19 and Dan Tehan vetoed five grants in 2020.

This time, Minister Robert defended his intervention, claiming that the projects were not ‘in the national interest’ or ‘value for taxpayers’ money’, despite the fact that the projects applications had been through a long-established, well-tested, and rigorous independent peer review process before being recommended for funding.

The reaction by senior university leaders such as ANU’s Vice Chancellor, Professor Brian Schmidt, and by the ARC itself, highlights how the acting minister stepped over some lines we might have thought were impregnable in a liberal democracy.

Sixty-three current and past ARC Laureate Fellows wrote to the CEO of the Australian Research Council and to Minister Robert expressing their concern about ‘the way that applications for 2022 ARC Discovery Projects were managed’. They observed that projects covering ‘topics like climate activism and China … are vital for the future well-being of Australia’. The ARC College of Experts also urged the government to ‘adopt standards in line with the Haldane Principle’, which holds that ‘decisions on individual research proposals are best made through independent peer review, and government ministers should not decide which individual projects should be funded’. They called on the government to legislate to ensure future ‘independence of the ARC and prevent political interference in research grants’, and called for changes to protect the ‘rigour and integrity of the ARC’s grant assessment process’ by ‘ending the Minister’s use of the National Interest Test to make unilateral decisions on individual projects outside of the peer review process’. Two members of the ARC College of Experts took the unprecedented step of resigning, stating that they were ‘angry and heartsore’ and had made their decision to resign ‘in protest’.

If we take a broader view of this particular minister’s veto of ARC recommendations, we can see a pattern of arbitrary decision making without reference to, or constraint by, principles of natural justice. As such, ministerial discretion constitutes an assault on the core liberal principle of natural justice. The Morrison government’s reputation for doing this is getting worse. Sometimes there is more than a sign of deep corruption. The ‘sports rorts’ case of 2019 depended on ministerial discretion overriding the due process established and managed by a relevant department dealing with hundreds of applications for community sports funding. A different and more serious kind of corruption associated with the exercise of arbitrary ministerial power has long operated in Australia’s decision not to recognise the right of asylum seekers to have rights. Currently, section 501(3) of the Immigration Act 1958 allows the immigration minister to cancel a visa arbitrarily on grounds of character or security and to set aside a finding made by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, all without appeal. The ‘robodebt’ project initiated by Scott Morrison in 2015 likewise highlights the damage done by untrammelled ministerial power riding roughshod over principles of natural justice, for which the $1.8 billion legal settlement of 2021 only partially recompenses its victims.

Fair procedures in decision making are a fundamental component of the rule of law. Australia’s common law recognises a duty to accord a person procedural fairness before a decision that affects them is made. As High Court justice Robert French, author of the 2019 report on academic freedom, noted:

A failure to give a person affected by a decision the right to be heard and to comment on adverse material creates a risk that not all relevant evidence will be before the decision-maker, who may thereby be led into factual or other error. Apparent or apprehended bias is likely to detract from the legitimacy of a decision and so undermine confidence in the administration of the relevant power (French 2014; 25/47).

Significantly, we have no formal right to appeal the decision by Minister Robert.

Finally, as concerning as the subversion of natural justice is, the Morrison government’s attack on academic autonomy is just as alarming. In our case, it silences researchers working with young people on a crucial policy issue.

Some 1,000 universities in ninety-four countries, including ten from Australia, have signed the Magna Charta Universitatum. The charter restates why universities are important. According to the Charter, a university ‘must serve society as a whole’ and that ‘to meet the needs of the world around it, its research and teaching must be intellectually independent of all political authority and economic power’. A central tenet of the Charter is that ‘freedom in research and training is the fundamental principle of university life’. That freedom is precisely what Minister Stuart Robert’s jackboots have damaged so profoundly.

On a positive note, Green’s Senator Dr Mehreen Faruqi has initiated a Senate Inquiry proposing that a bill first introduced into the Senate in 2018, designed to remove the veto powers from the minister, be reconsidered. It is a long overdue reform that might help mitigate some of the harm this government has done to Australia’s universities.

Professor Judith Bessant, School of Global, Urban and Social Sciences, RMIT University.

Associate Professor Faith Gordon, ANU College of Law, Australian National University.

Professor Rob Watts, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University.

This article, one of a series of ABR commentaries addressing cultural and political subjects, was funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy.jpg)