- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

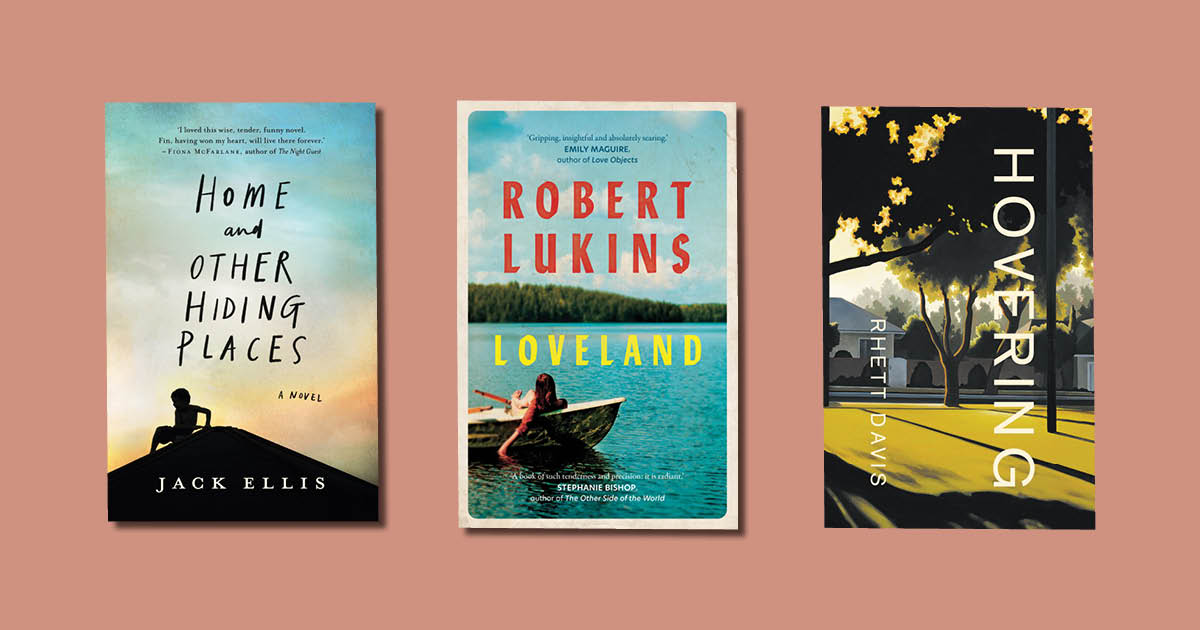

- Custom Article Title: New fiction by Jack Ellis, Robert Lukins, and Rhett Davis

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mutable worlds

- Article Subtitle: Ambition and audacity

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen,’ Vladimir Lenin has been credited with saying, with reference to the Bolshevik Revolution. It’s a sentiment that immediately springs to mind when reading Jessica Stanley’s A Great Hope, a début that, while not billed as historical fiction, is deeply concerned with history and its making.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Debra Adelaide reviews 'Home and Other Hiding Places' by Jack Ellis, 'Loveland' by Robert Lukins, and 'Hovering' by Rhett Davis

Ellis offers a compelling story about a family that is divided, directionless, and under pressure. The focus is on eight-year-old Fin, recently brought to live in Sydney with his grandmother by his mother, Lindy, who is trying to flee her demons, find a job, and generally prove that she is not the loser everyone seems to think she is.

This is a world where people struggle to be decent but are weak, compromised, or slapped down at every turn. Lindy is deluded and unstable, set up to be a victim, while Fin’s father is unreliable and mostly absent, yet they are both trying as hard as their circumstances allow. No character is judged or stereotyped, and even Fin’s cold and disapproving grandmother surprises everyone, including the reader, at the end. There are other strong characters: Fin’s great-grandmother, the chain-smoking Josie, and the neighbouring kid, Rory, who almost steals the show with his military turn of phrase thanks to the influence of his grandfather, and his old-school survival skills, which he passes on to Fin.

Despite the serious dysfunctionality of its characters, the story is far from bleak. Fin is sweet-natured, innocent, and totally likeable. He sets off on mad adventures such as attempting to sail to New Zealand with Rory in a tiny boat, thinks his grandmother is trying to poison him, runs away at the threat of trouble, but maintains a core of kindness and generosity that belies his youth.

In one scene near the end of the novel where Fin’s father is negotiating with him, we share a threshold moment of clarity about Fin’s fugitive parent and his own life, his sense that he’s about to leave the world of childhood adventures and road trips and enter a new, as yet uncharted, one. He is at once devastated by and understanding of his father’s choices. The details of this scene are so poignant that I felt like my heart had been taken out and squeezed then replaced in a slightly different spot.

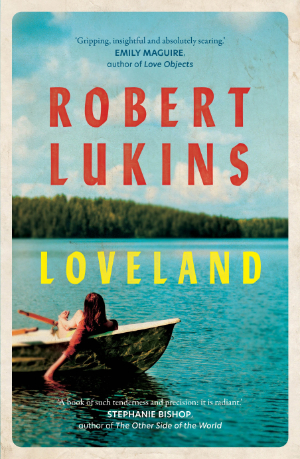

Loveland by Robert Lukins

Loveland by Robert Lukins

Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 344 pp

Robert Lukins’s Loveland promises to be an ambitious novel, setting up mysteries and pursuing its storyline through the point of view of two main characters. In Queensland, May hears that her grandmother has died and left her a property previously unknown: a house in Nebraska, in a former amusement park called Loveland. Meanwhile, a backstory set in the 1950s focuses on her grandmother as a newly married young woman, and builds to the dramatic revelations as to why she journeyed halfway across the world and kept the details of her previous life a secret.

May leaves her husband and son and travels to Loveland to settle the inheritance, but starts to forge friendships with some of the locals, including a woman who reveals she once had an affair with May’s grandfather. Changing her mind about selling, May tells her husband over the phone that she’s leaving him, provoking his unexpected arrival later on.

At first, Loveland appears alluring in its historical reach and highly visual setting, while the two-handed narrative provides an interesting structure. There is a spectacular fire in the background of the story, signalled in the prologue, along with some shocking violence. And yet the passive voice, the arbitrary action, and Lukins’s penchant for broad-brush scenes rather than details mute the novel’s impact and keep the characters at a distance. The prose is wordy, so that simple actions like answering a phone seem overly significant, imposing an unnecessary weight on the story. But the biggest problem is the passive female characters, and the unrelentingly sinister males. May has chosen to marry young to an abusive, controlling man, as if doomed to repeat the mistakes of an earlier generation, but the reason why is never explained. Mysteries like these demand much more context.

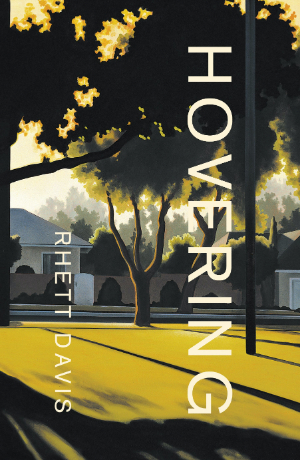

Hovering by Rhett Davis

Hovering by Rhett Davis

Hachette, $32.99 pb, 293 pp

You’ve got to love a novel that takes risks, tries something new, and ultimately gives you a good shake-up. Rhett Davis’s début novel, Hovering, balances on the edge of implausibility but remains entirely convincing. This is partly because right at the start we are given something ordinary and familiar – the arrival home from overseas of Alice, an artist and activist – and partly because Davis has such a deft hand. We first meet Alice just before landing, peering out the aeroplane window at Fraser, a city that is like Melbourne, but not. The place seems different after sixteen years. But then the taxi she takes to her old family home is blue, not yellow, and although the driver goes in the wrong direction, they arrive all the same. Alice is coolly greeted at the door of the family home by her younger sister Lydia.

Homecomings, sibling rivalries, personality clashes: Hovering exploits simple and familiar scenarios. But something is a bit off, and all this is hinted at before the end of the first paragraph. So much is effortlessly dealt out in the first chapter – indications that Alice is fleeing some conflict, or worse; her very mixed feelings about having to return; a brief rundown of her years overseas; Lydia’s feelings expressed in a terse email exchange – that I was hooked.

Meanwhile, the city is under a mysterious threat. Buildings, lawns, parks, streets – everything is liable to shift place or change size and colour from one day to the next; even the family home eventually gets a lofty relocation. The residents accept these changes with resignation, although feverish theories abound as to the cause. Instead of weather reports or bushfire alerts, they get daily bulletins on the changes to their world. The bizarre quickly becomes commonplace in this novel. All through I was persistently reminded of a Howard Arkley painting. Stare long enough at his technicolour, airbrushed suburbanscapes and they begin to look normal.

Within the family there are shifts and variables. Alice’s sudden and unexplained departure years earlier left Lydia feeling abandoned. Their parents have retired to a life of pleasure-seeking on a series of artificial holiday resorts. Lydia’s teenage son George now only communicates via emails and text messages. In the meantime, Lydia suspects her sister is a fake, or a clone. Something about Alice is not quite right: she can now cook, for a start.

Is Lydia justified in her suspicions? She spends her days data-mining and analysing, her nights shut in her bedroom gaming. What would she know about the real world? But that is the point. The real world is mutable, called into question at every turn of the novel. The virtual city that George is quietly creating in his bedroom might be more reliable and authentic.

Hovering is an audacious and original novel. There is a lot going on as Davis explores contemporary anxieties about place, ownership, and landscape – not to mention that whole question about the blurring of reality. He uses a range of forms and genres – radio scripts, computer coding, transcripts of feeds, tables – and while not everything he throws at the novel sticks, the serious questions raised about insecurity and miscommunication compensate for that. This whole novel is just so quirky and appealing that it will be interesting to see what Davis does next.

Comments powered by CComment