- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Hearts on sleeves

- Article Subtitle: Kári Gíslason’s latest saga

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In his extraordinary journey through Iceland’s history, Saga Land (2017, with Richard Fidler), Kári Gíslason described Icelanders as ‘being reserved’ and ‘a bit severe’ at first glance, likening them to the Hallgrímskirkja church that looms over Reykjavik with its enormous basalt column wings and stony façade. The first three days I spent alone in that city gave me a wholly different impression of its people. On my first day there in 2013, I was greeted by what appeared to be most of the city’s population lined up on the Lækjargata strip waving flags, smiling from ear to ear, and dancing as the annual Gay Pride parade rolled by in all its garish joy.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Dilan Gunawardana reviews 'The Sorrow Stone' by Kári Gíslason

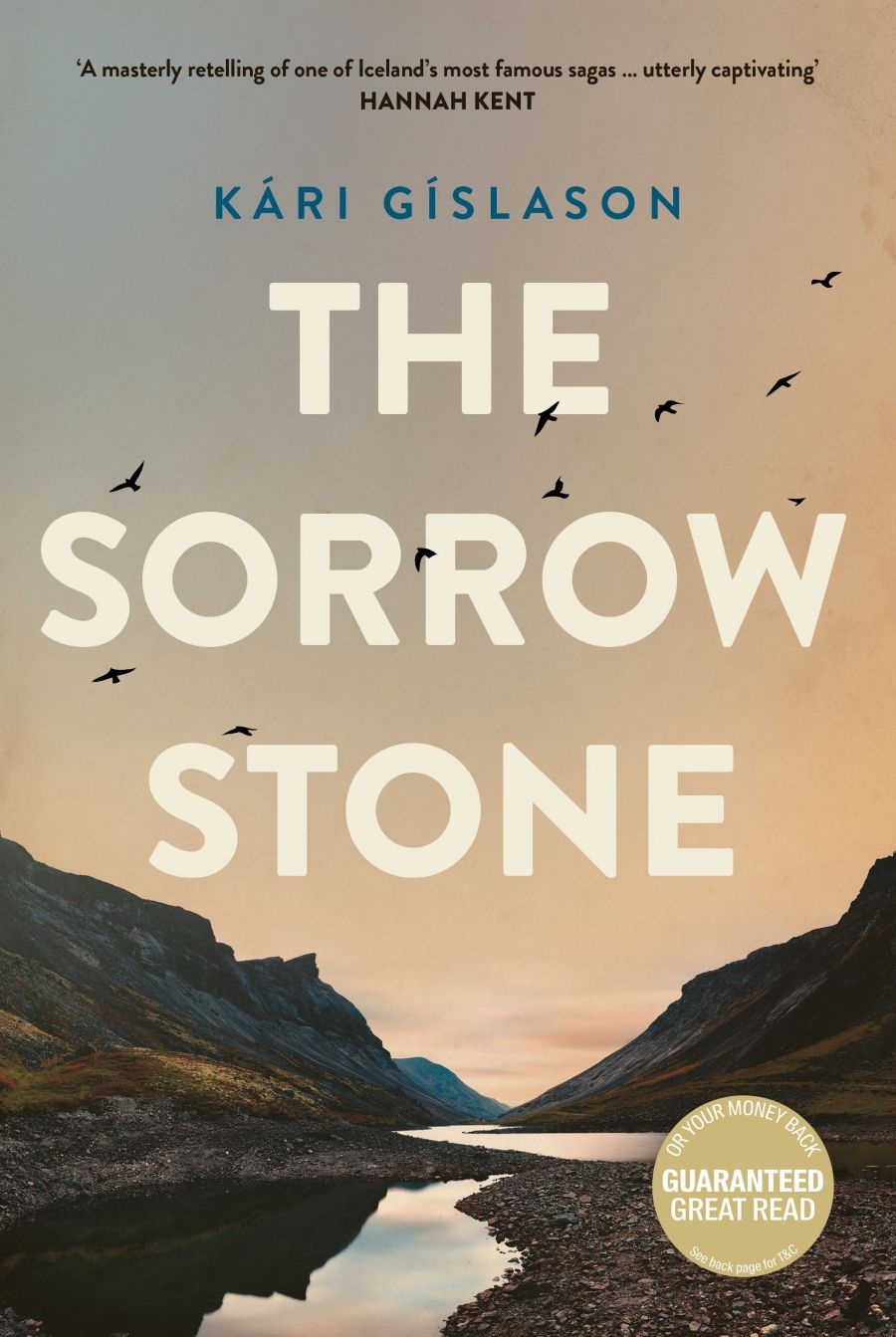

- Book 1 Title: The Sorrow Stone

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $32.99 pb, 240 pp

It’s not a stretch for me to surmise that Icelanders, contrary to how they are often perceived, actually wear their hearts on their sleeves. As Gíslason observes in Saga Land, ‘it doesn’t take much to get under the sternness’. Thanks to the authors of the Icelandic Sagas, including Gíslason’s direct ancestor Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241), we know that the fates of Icelanders across centuries are often dictated by matters of the heart and other organs.

In the Njáls Saga, Hrútur’s manhood is cursed for sleeping with the ageing queen mother of Norway. This leads to a chain of bloody events over decades. In the Laxdæla Saga, the close friends Kjartan and Bolli both fall in love with the beautiful Guðrún, leading to their mutual destruction; and in the Gísla Saga, the outlaw poet Gisli kills a man deemed unsuitable for his elder sister Thordis, resulting in their family’s exile to from Norway to Iceland, a love quadrangle across neighbouring farms, and Thordis stabbing the hitman she paid to kill her brother (retribution for killing two of her lovers). It’s this saga that forms the basis of Gíslason’s second novel, The Sorrow Stone.

Kári Gíslason (photograph by Nicholas Martin)

Kári Gíslason (photograph by Nicholas Martin)

The backdrop of Gíslason’s retelling shifts between the rural fjords of Norway and Iceland at the midpoint of the tenth century ce; Hakon the Good of Norway, indoctrinated at the English court, spreads the word of Christ across his kingdom, and Vikings return to their home harbours in longships filled with treasures and slaves. In Iceland’s Westfjords, a woman flees across farmlands with her twelve-year-old son. They carry a shield to protect them from the icy winds, and a cursed blade that moments ago was embedded in the leg of a man she was honour-bound to kill. This saga’s heroine is Disa, a resident of the ‘shit-soaked island of storm and rocks’ who was exiled years ago at a young age from her home in the ‘warmth and light’ of Surnadal, Norway. As Disa is pulled along by the whims of the men who smother her throughout her life – her father, her brothers Gils and Kel, her lovers Bo and Grim – we learn of the tragic events leading up to the birth of her son, Sindri, and of their eventual escape.

Subtle, well-paced, and compelling, the narrative switches between the urgency of Disa and Sindri’s flight and Disa’s pluperfect telling of her own saga before the plotlines knit together. Gíslason’s expansive knowledge of Icelandic history and culture lends authenticity to his characters’ actions and musings. Through direct, non-flowery prose, he taps into the animism that endured in the tenth-century Norse psyche with descriptions of water in the bays as ‘the colour of dark steel’, ships returning to harbours like ‘whales full of treasures to cut open and spill into the valley’, and mornings in autumn taking ‘longer to take shape’. Not yet tethered to Christian notions of morality, the men of The Sorrow Stone carry out honour killings dutifully and (mostly) with the same amount of reluctance as slaughtering livestock for sustenance – nobody here can afford to turn the other cheek. As Disa remarks: ‘Father said preachers spoke more shit than our farmhands.’

Gíslason wisely places the larger geopolitics of this era in the background and teases out the strands of human yearning that lie hidden between the succinct accounts of families, conflicts, and scandals in the Sagas. The perspectives of women are largely missing in these foundational texts, and Gíslason imbues his protagonist Disa with desire and a vulnerability that allows readers to feel the leaden impact of her losses and to view the male characters in her orbit through a more critical lens. After rattling off several poetic names for the ocean – ‘chain of man’, ‘paths of ships’, ‘belt of the islands’ – Gils only has one descriptor for the heart: a sorrow stone, to which Disa asks, ‘no more than that?’ suggesting a pathos behind Gisli’s killing of Thordis’s lovers in the original saga, or perhaps a forbidden, unrequited desire.

Few authors have such an intimate and academic understanding of Iceland’s harsh and beautiful landscape, the essence of its people, and the importance of weaving stories to form a personal and national identity as Kari Gíslason. As we stand back and regard his tapestry, a perspicacious study of love in various forms – potent, forbidden, furtive, unrequited – reveals itself.

Comments powered by CComment