- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The trouble with ideas

- Article Subtitle: How Dostoevsky wrote his way to salvation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There really isn’t another biographer like Joseph Frank – nor a biography to place beside his 2,400-page, five-volume life (1976–2002) of Fyodor Dostoevsky, the wildest and most contradictory of the great nineteenth-century Russian novelists. Frank set out in the late 1970s – a time when historically grounded literary scholarship was losing favour in the academy – to fix Dostoevsky (1821–81) in the complex matrices of Russian history, politics, religion, and culture. An author who had been read in the English-speaking world as a hallucinatory thinker, somewhat detached from reality, could now be seen as one fully imbricated in his era and milieu.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

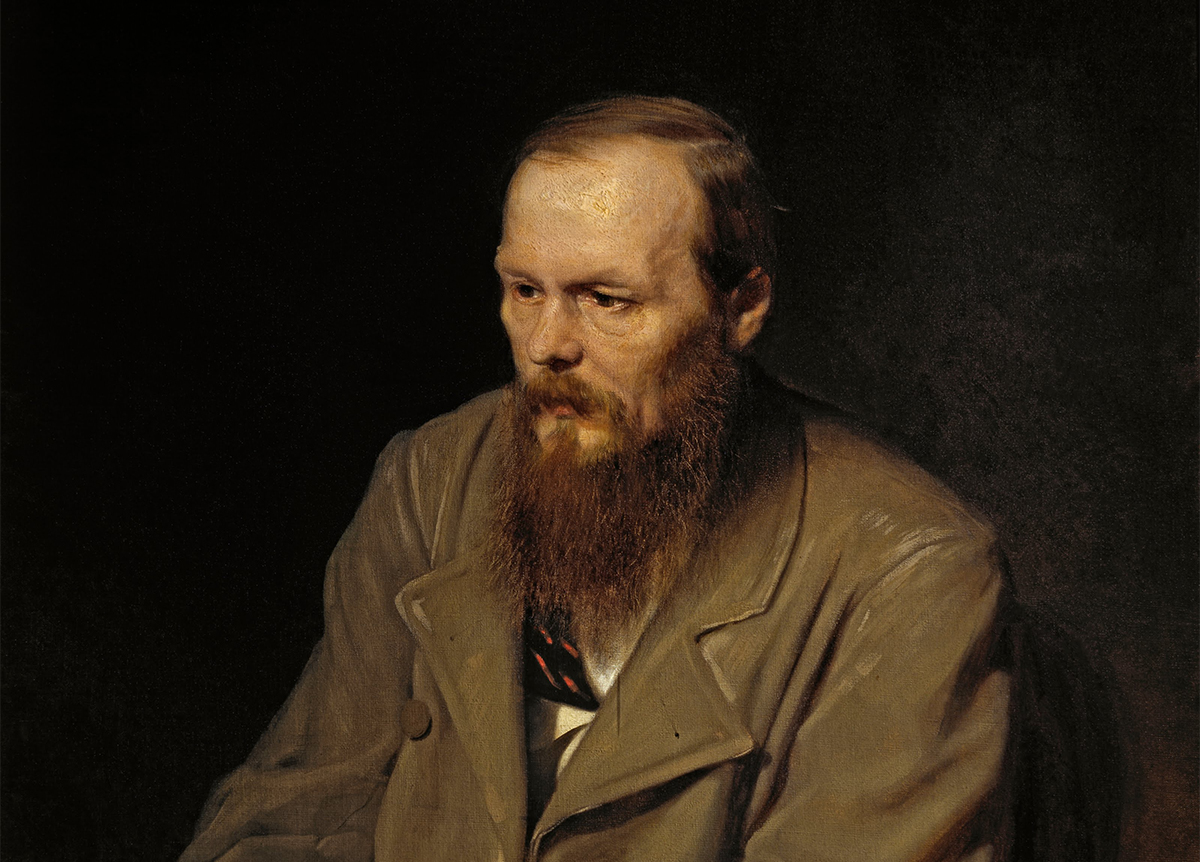

- Article Hero Image Caption: Portrait of Fedor Dostoyevsky, painted by Vasily Perov in 1872 (Wikimedia Commons)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Portrait of Fedor Dostoyevsky, painted by Vasily Perov in 1872 (Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Geordie Williamson reviews 'The Sinner and the Saint: Dostoevsky, a crime and its punishment' by Kevin Birmingham

- Book 1 Title: The Sinner and the Saint

- Book 1 Subtitle: Dostoevsky, a crime and its punishment

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $53.25 hb, 432 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/7mxbRY

Frank’s project furnished a model to which later life writers might at least aspire. Think of Reiner Stach’s exhaustive three-volume life of Kafka (2002–13), which located the Czech fabulist in the welter of Mitteleuropan life in the twentieth century’s early decades – or of Michael Gorra’s ambitious The Saddest Words (2020), a rereading of William Faulkner’s body of work through the prism of the American Civil War. Gorra, indeed, provides cover copy praise for Kevin Birmingham’s The Sinner and the Saint, a work that replicates Frank’s encyclopedism but funnels it into a single storyline, that of the real-life inspiration for, and the genesis and writing of, Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866). But why Crime and Punishment and not, say, The Brothers Karamazov (1880) or The Idiot (1869) – both arguably greater achievements? Or even Notes from a Dead House (1862), that hinge-work describing Dostoevsky’s years in Siberian exile?

In a dramatic opening chapter, which zeroes in on the earliest moments of the novel undertaken while Dostoevsky was trapped, ill and penniless in a hotel in the German resort town of Wiesbaden during September of 1865, having lost everything at roulette, Birmingham persuasively argues that Crime and Punishment is both the key that opens the lock to his late creative efflorescence (‘four of the greatest novels in Russian literature – in all literature’) and a world-changing text in its own right:

Decades later, it seemed clear that the Russian had started a revolution in ‘the artistic thinking of humankind’ – that’s how the literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin put it. He argued that Dostoevsky’s novels ‘provide a new artistic model of the world’. His novels are gatherings of autonomous voices interacting with one another beyond the control of an overriding authorial voice.

‘Bakhtin,’ concludes the author, ‘called this innovation the polyphonic novel, a form that transcends the simplicity of centuries of monologic art.’ Birmingham is content to cede to the older formalist critic closer readings of the novel; however, there is another angle he wishes to explore. And that is the way the radically new form inaugurated by Dostoevsky interacts with the world as it is: ‘a narrative where notions and theories, dreams and hallucinations seep into a criminal investigation, a quest for material evidence of a crime’.

St Petersburg – a tsar’s grand dream of a capital plonked down in a frozen, misty swamp – is both the novel’s physical setting and an architectural metaphor for the novel’s weird meeting of the empirical and illusory.

Birmingham’s thesis, one that he explores in the coming chapters with both scholarly rigour and a dash of Dostoevsky’s own febrile poetry, is that Crime and Punishment is not a novel of ideas – it is ‘a novel about the trouble with ideas’:

Dostoevsky’s novel is about how ideas inspire and deceive, how they coil themselves around sadness and feed on bitter fruit. It is about how easily ideas spread and mutate, how they vanish, only to reappear in unlikely places, how they serve many masters, how they can be hammered into new shapes or harden into stone, how they are aroused by love and washed by great rains and flowing rivers.

‘It is about how ideas change us,’ writes Birmingham, ‘and how they make us more of who we already are.’ Which is to say, The Sinner and the Saint is a book about the way those theories and arguments that surrounded Dostoevsky during his youth and maturity in his native Russia – and right across Europe and the New World – were absorbed into the author’s mental bloodstream and modified in the process.

The Sinner and the Saint proceeds, then, as a series of chapters in which an account of Dostoevsky’s intellectual development alternates with an exploration of the life and crimes of a man who would furnish the model for Raskolnikov: the poet–murderer Pierre François Lacenaire (1803–36).

Lacenaire first came to Dostoevsky’s attention in the early 1860s, when the author and his brother Mikhail were combing European journals for material worthy of translation and publication in their first magazine. It was in a French collection of infamous criminal trials that the author happened across Lacenaire’s 1835 trial for double murder and his eventual execution. What fascinated the Russian about Lacenaire was his determination to provide intellectual justifications for his crimes. In a world where criminals were almost regarded as a sub-human species, Lacenaire was a polished product of the French bourgeoisie. He went to university and intended to study for the law. He wrote poetry and was familiar with the radical fringes of early nineteenth-century thought. That such a man might attack and murder in cold blood a man and his mother using a sharpened file, and then have the temerity to claim his criminal actions were not only justified but the logical outcome of a society in which inequality was enforced by the state, made Lacenaire something new.

Michel Foucault considered the attention and even fame granted to Lacenaire as the expressions of a shift from public reverence for older folk heroes to that of the bourgeois anti-hero, a romantic criminal whose story prefigured the modern genres of true crime and the novel of detection. But Dostoevsky saw in Lacenaire something closer to home: a confusion of thought and impulses for which he felt personal sympathy but also a degree of repugnance. Birmingham shows how Dostoevsky’s time in Siberia exposed him to men who had murdered and yet who were in all other respects ordinary. He came to appreciate that even the most terrible crimes may be committed by individuals caught up in circumstance. And the feudal police state of tsarist Russia had much circumstance to offer.

Still, Dostoevsky was fundamentally altered by his time in Siberia in other ways. The Western liberal ideas that fed his youthful political activism – the egoism of Max Stirner, the utopian socialist thought of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon or Charles Fourier – were replaced by a conservative, if idiosyncratic, Russophilia. Western individualism became for the Russian author a social disease of which Lacenaire was a morbid symptom.

If Birmingham spends the first half of the book laboriously wheeling these opposing positions into line, it is worth the wait. By the time we have circled back to the ‘small, mid-level inn situated among beer houses across from the railway station’ in Wiesbaden, the structures of thought and feeling that formed Dostoevsky have been exhaustively laid down. What follows is an account of creation, in which Birmingham brings microscopic detail and a sense of drama to the composition of Crime and Punishment.

We read of the hunger and desperation the Russian faced at that moment – of the scattered notes and ideas gradually gaining coherence as he wrote by the stump of a candle the hotel servants refused to replace. The ideas came fast: Dostoevsky wrote fifty pages, then a hundred, all in a few days. We learn how the author filled his available notebooks then turned them upside down to continue writing. ‘On some level,’ Birmingham suggests, Dostoevsky ‘had been playing a game of brinkmanship with himself, engineering a moment of literary salvation’:

He had pretended that escaping to Europe and winning at roulette would be his salvation. The hand of God would rescue a virtuous, long suffering man through the unlikely instrument of a tiny ivory ball. And when the salvation didn’t come, when he was utterly ruined, his eyes would be opened at last, and he would realize that he could be saved only through writing.

‘So by the time he picked up his pen in Wiesbaden,’ writes Birmingham, ‘the ink that flowed onto the page had become the product not of a secular confession but of a genuine calling ... The story taking shape in his notebooks was God’s true saving instrument.’

If Joseph Frank’s biographical project worked like a map of the author’s life drawn on a one-to-one scale, The Sinner and the Saint takes a single, mighty tributary of Dostoevsky’s career and sails it from mountain source to river delta. It makes for a thrilling ride.

Comments powered by CComment