- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Breaking and entering

- Article Subtitle: Piecemeal transgressions of a small town

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australiana opens with a break-in. Lifting away a flyscreen, strangers climb into a man’s house, help themselves to his biscuits. The crime doesn’t feel important – it’s the fourth in a month, we’re told – but the intrusion does. It evokes the entanglements of small towns, the way in which lives intersect, physical proximity breaking down the barriers of class and culture and personal choice that can divide urban populations into subcultures. As a declaration of intent, the image of trespass is pretty clear: there is no real privacy in this town, and as readers we’re about to gain access.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Yumna Kassab (photograph supplied)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jennifer Mills reviews 'Australiana' by Yumna Kassab

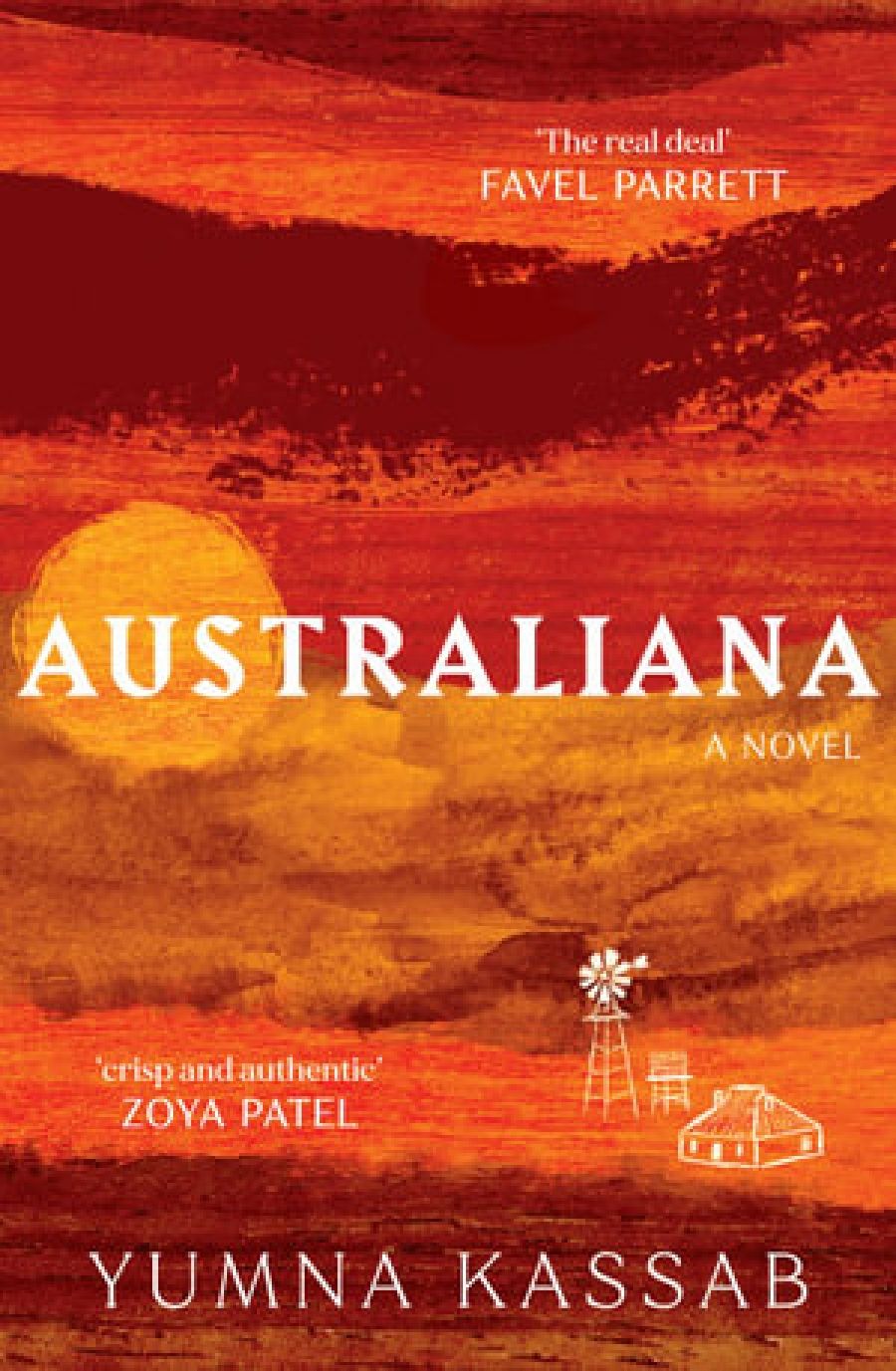

- Book 1 Title: Australiana

- Book 1 Biblio: Ultimo Press, $32.99 pb, 292 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Gjq0qL

Kassab moves nimbly from character to character, sometimes barely touching the ground before lifting off again. Like a long, immersive tracking shot in film, the technique brings the reader into the book’s world quickly and constructs an illusion of stories unfolding before our eyes in real time, offering a voyeuristic pleasure.

This effect is occasionally punctured by leaps in time, sudden movement between event and memory. The temporality interrupts the illusion, but after a while the choice makes sense; it’s closer to how time actually works in our inner lives. We fall and rise through memory as we move through space. This eventfulness, this layered being, is perhaps more prominent in small towns or neighbourhoods where one has lived a long time. That some people are marked by what happened to them years ago, or that some relationships remain limited by past events, feels authentic. Small communities share lifetimes of connection and transgression, and such stories are rarely consistent in memory. It’s promising territory for a novel.

The community in question is in regional New South Wales, the region in and around Tamworth, where Kassab has been living and teaching after growing up in Western Sydney. Her first book, The House of Youssef (2019), drew on direct experience, taking the reader into the milieu of Lebanese-Australians, first and second-generation migrants. That book also deployed microfictional techniques to enter homes and inner lives at points of crisis.

There are traumatic and difficult events here, too: a break-up, a suicide, various failures of duty. Acts of violence, arson. Drought and flood. The quickness of movement can sometimes give these stories an iterative sense of despair or bitterness that is common in fiction about regional Australia. I found myself wondering why hurt is so much easier to depict than the deep care that can also define small town life.

A polyphonic approach calls for restraint. Kassab’s eye roves coolly, and there is a matter-of-factness to the interiority of her characters that is often subtly powerful, though it can veer into cliché (‘Water off a duck’s back’,‘the final straw’, etc.). Drought and poverty are ever-present, while other challenges are suggested, such as pollution from mining and the climate crisis. A father dreams: ‘Fields freedom fantasies failure.’ A child’s voice appears as a single, floating paragraph. A light touch becomes more useful as the material darkens, as slowly the stories begin to ease into a kind of pastoral horror.

Later sections of the book offer more integration. ‘The Blind Side’ deals with one farmer’s transgressions as a town metes out its own version of justice. Over several chapters, a portrait of relationships and shared history gives a sense of entanglements through time. Here, Kassab’s commitment to realism is at its most pronounced, even prompting a declaration that ‘names and places have been changed’, lifting off the flyscreen between fiction and documentary.

Elsewhere, the attachment to realism drifts away altogether. In ‘Pilliga’, a ghost story, Kassab explores the Australian gothic, evoking a haunted landscape, the bush as a site of death and disappearance. ‘What do people do out here? They disappear,’ says one character. Later: ‘We think it is an ancient land but he tells me it is a burial ground.’

As this story’s narrator toys with skulls in a dry riverbed, I can’t help recalling Tony Birch’s notion of the supernatural or haunted landscape as a salve for historical violence, a displacement of human accountability. When the Pilliga has been the subject of such a thorough investigation as Eric Rolls’s A Million Wild Acres, this feels like a missed opportunity for more depth.

To title this novel-in-stories Australiana is a provocation. While aiming to interrogate national myths and identity, Kassab risks going over old ground, reinforcing the notion that the rural context offers authenticity, albeit bleak, or accepting the notion that some nebulous identity lies to the west of the Great Dividing Range. Questions about why these myths persist, about colonisation and the politics of land, are passed over in the detail of ordinary lives. This is where the gestural falters.

The final section of the book is a poetic treatment of Captain Thunderbolt’s enduring presence. This feels tacked on, reinforcing a suspicion that Australiana could have been packaged as a short story collection. A novel can sustain plenty of formal fragmentation, but the more interesting stories here are those that connect.

Kassab is a writer adept at breaking and entering: at stepping into the lives of others and bringing us their fears and hurts. The patchwork technique works well, and when it offers insight into a community and its relationships, it can be very satisfying. But Australiana doesn’t quite fulfil the promise of that first uneasy trespass.

Comments powered by CComment