- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Litter, glass, black soft dust’

- Article Subtitle: A scattergun study of wartime writers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In late March 1941, more than six months into the relentless German aerial campaign that was then destroying great swaths of London’s fabric and spirit, Virginia Woolf filled the pockets of her heavy overcoat with stones and waded into the River Ouse. Her suicide occurs halfway through Will Loxley’s scattergun study of English writers and writing during the war, though its inevitability haunts the first half of the book, as claustrophobic as the pea-soupers that had defined London’s self-image in the centuries before the Blitz took on that singular responsibility.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Kildea reviews 'Writing in the Dark: Bloomsbury, the Blitz and Horizon Magazine' by Will Loxley

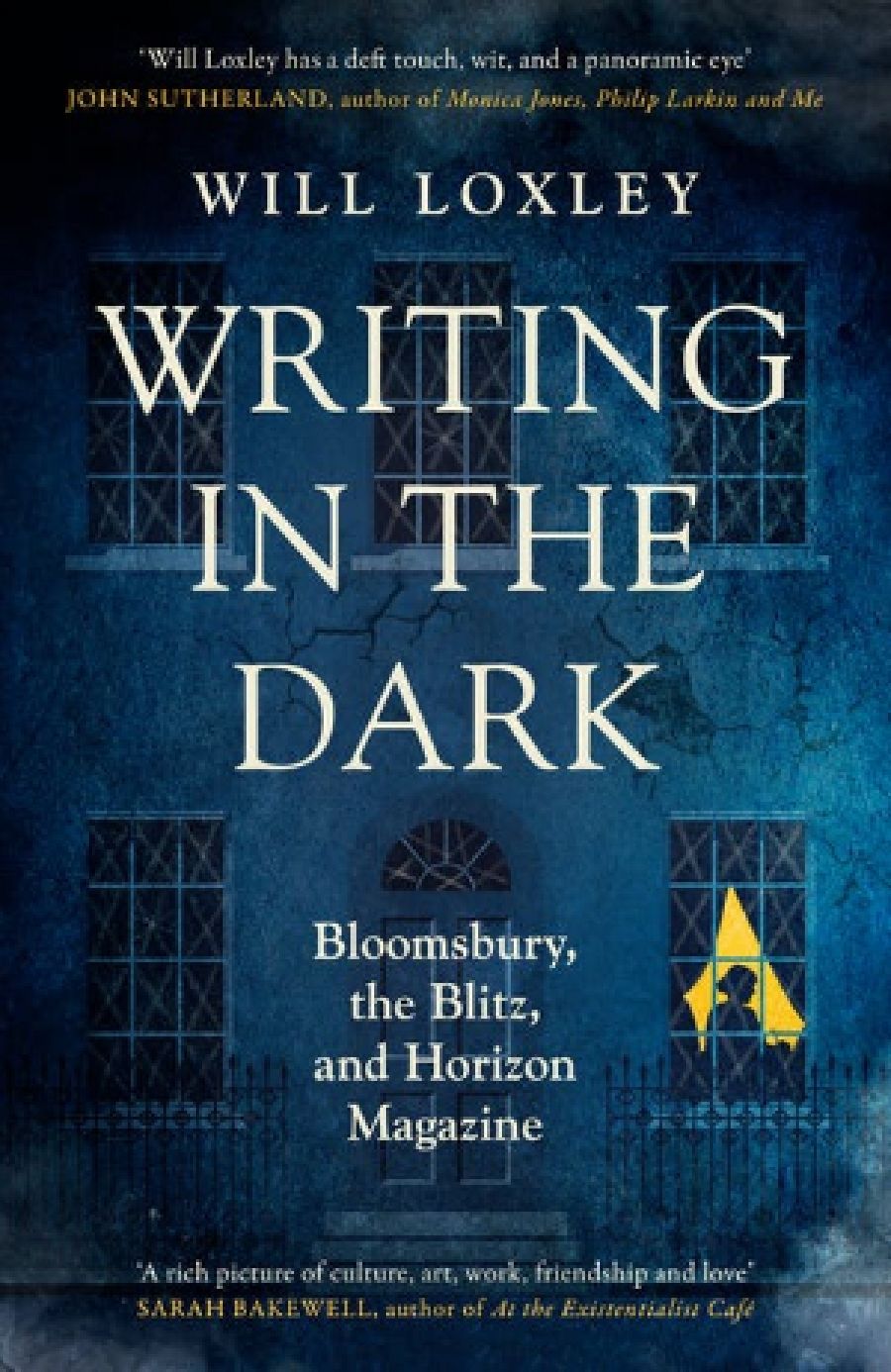

- Book 1 Title: Writing in the Dark

- Book 1 Subtitle: Bloomsbury, the Blitz and Horizon Magazine

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $32.99 pb, 399 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/4eKdO0

Loxley presents Woolf prior to her suicide as a slowly dimming lodestar, her diminishment marked by sudden, thrilling flare-ups. A new generation of writers and thinkers had emerged from the boggy catastrophes of World War I – a generation dismissive of the cack-handed architects of the world’s predicaments, and one all too wary of what it sensed was coming – and its members wanted their published words to mean something.

Woolf disliked this generation’s cynicism and doubted all the Marxist and anti-fascist panaceas it conjured along the way. It was a generation that too easily evinced ‘first discomfort; next self-pity for that discomfort; which pity soon turns to anger’. Why should poets be politicians? Vanity Fair pootles on perfectly well without reference to the Battle of Waterloo, until that delicate moment when George Osborne’s death in the field demands a temporary recalibration. It’s not that Woolf couldn’t incorporate contemporary events into her writing (‘All again litter, glass, black soft dust, plaster powder,’ she describes the aftermath of the raid that badly damages her former apartment in Tavistock Square); it’s more that she chose not to.

Horizon Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 1, published September 1961 (American Heritage Foundation/Wikimedia Commons)

Horizon Magazine, Vol. 4, No. 1, published September 1961 (American Heritage Foundation/Wikimedia Commons)

This interwar sea change in English literature is not the main focus of Loxley’s book, though it shapes a very good chapter on the tensions that grew between established and emerging writers as the 1930s marched on. (‘Come on, Virginia, don’t disgrace the older generation,’ Leonard Woolf gently admonishes his wife after she has savaged some luckless young writer at dinner.) Yet the two institutions Loxley has chosen to bookend his tale – the Hogarth Press, which Virginia and Leonard founded in 1917, and Horizon magazine, Cyril Connolly’s buccaneer initiative of 1939 – do underscore the cultural, stylistic, and existential changing of the guard then underway.

Of course, W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood are the bright sentinels: their defection to America in 1939 exposed the considerable fault lines in what Samuel Hynes later heroically attempted to corral together as the Auden Generation. Yet this well-trodden ground – the denunciation in the House of Commons; the earnest, homophobic dismissal in editorials of the pansy poets; Evelyn Waugh’s snarky portrayal of the two in Put Out More Flags – is passed over soon enough and an altogether richer crew is assembled. George Orwell, John Lehmann, Stephen Spender (inevitably), and Waugh all appear. Orwell is initially either a prig or a prude, dismissing the ‘so-called artists who spend on sodomy what they have gained by sponging’, though he more than makes up for his lapses of judgement with a burning sense of righteousness (still with us today), not least in his dogged prediction and advocacy of an independent India. A giggly-drunk Dylan Thomas (at times a violent one too) shows up, appeasing his near-daily hangovers with a morning double-shot of whisky, a pint of bitter, and then spaghetti bolognese. (In the year after his early death, his drunk widow, Caitlin, attends the first performance of Under Milk Wood only because Louis MacNeice drags her there.)

Arthur Koestler has only a walk-on part, but what a beauty it is. In his essay for Horizon in October 1943, he pens the most chilling and prescient line of the whole gang – the equal of anything Orwell wrote in Spain or Waugh in Abyssinia. ‘There are trains which are scheduled on no timetable, but they run all over Europe. Few people see them because they start and arrive at night.’ When Osbert Sitwell accuses him of playing a ‘very wicked’ trick on his unsettled readership, Koestler issues a retort that prefigures the trials at Nuremburg, the books by W.G. Sebald, and the wondrous, great social-democratic experiment in West Germany from 1949 onwards: ‘As long as you don’t feel ashamed to be alive while others are put to death and guilty, sick, humiliated, because you were spared, you will remain what you are: an accomplice by omission.’

Does it all add up to much? Yes and no. There is no literary criticism, bar the lovely final ten pages, which read a little as if Loxley has rescued them from another landing place, perhaps one more scholarly guarded. And for all the bombs and blackness, London is nowhere near exciting enough a character; these astonishing talents certainly wrote in the dark, but so too did they fuck and fight and feed and feud in it. With this generation and this city, none of these activities ever tires us, no matter the passage of time. Less is sometimes, um, too little.

Yet Loxley has identified his own night train, one that travels alongside Penguin Books and Brideshead Revisited (1945), but which ultimately goes its own way. He has not obeyed Virginia’s firm direction (‘For heaven’s sake, publish nothing before you’re thirty’), and nor has he supplanted Stephen Spender’s The Temple (1988) or Humphrey Carpenter’s The Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh and his friends (1989) or even Matthew Spender’s A House in St John’s Wood: In search of my parents (2015). Yet in choosing a pudgy editor and critic as his hero – one who junked his initial wartime determination to ‘keep the calendar at 1938’ in order to stand proudly, if often disapprovingly and jealously, with the ramshackle Auden Generation – he has found his own way through the crowd.

Comments powered by CComment