- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Baudelaire’s dream

- Article Subtitle: Gary Catalano’s distinguished prose poetry

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The poetry community in Australia, as in the United Kingdom, has been slow to accept prose poetry as a legitimate poetic form. Yet there have been celebrated exponents of prose poetry over nearly two centuries – and even longer if the prose component of the Japanese Haibun, developed by Matsuo Bashō (1644–94), is understood as prose poetry.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Hetherington reviews 'Collected Prose Poems' by Gary Catalano

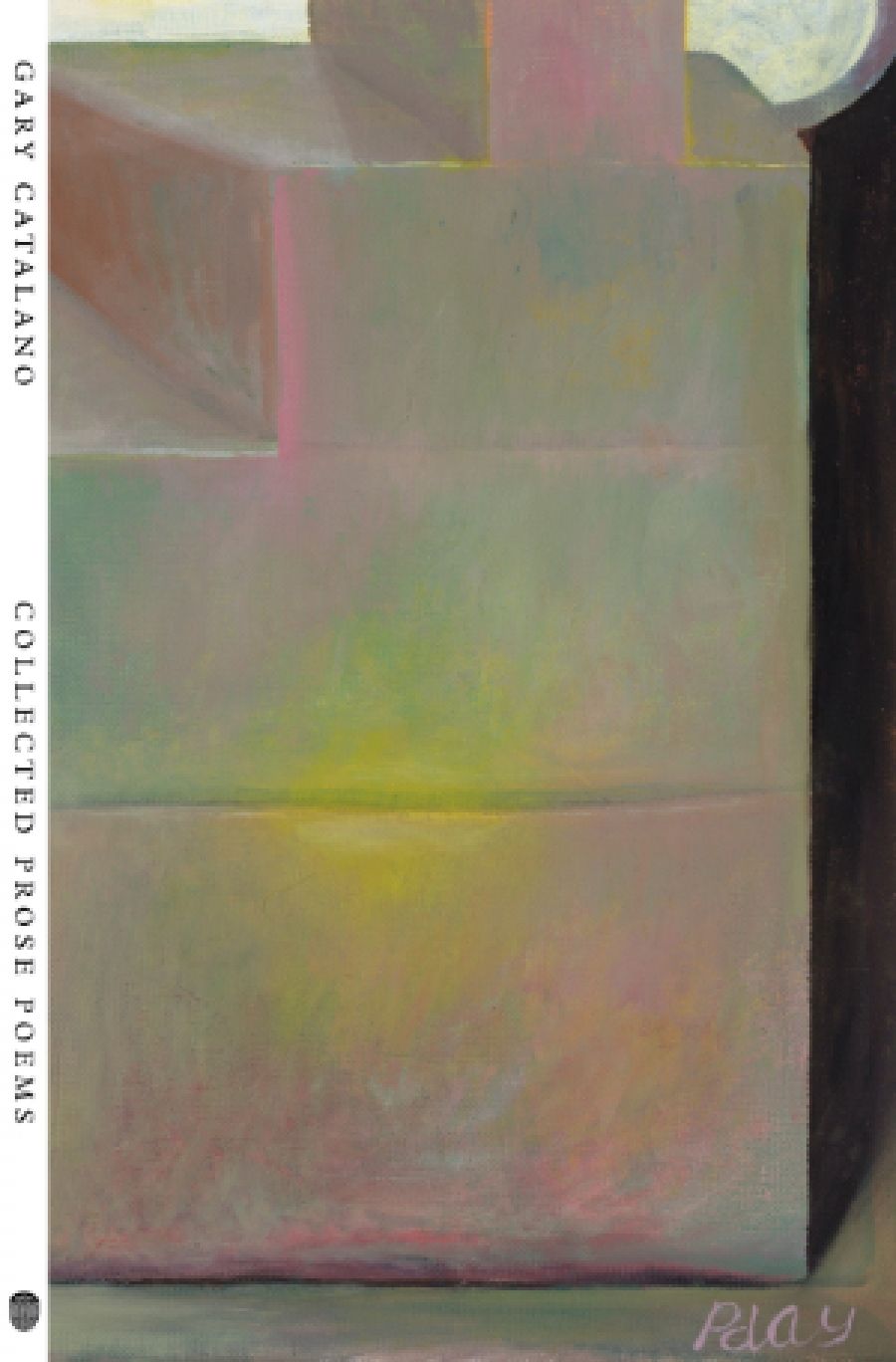

- Book 1 Title: Collected Prose Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Life Before Man, $24.99 pb, 232 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/6bqPRq

The European prose poetry tradition was started in France by Aloysius Bertrand (1807–41) through the 1842 publication of the quirky Gaspard de la Nuit – Fantaisies à la manière de Rembrandt et de Callot. Bertrand’s work initially sold few copies but was a powerful influence on Le Spleen de Paris by Charles Baudelaire. Published posthumously in 1869, this volume famously inaugurated the modern prose poetry tradition, and in its preface Baudelaire stated that he ‘had dreamed of the miracle of a poetic prose’. Since then, the list of well-known French prose poets has grown long, including luminaries such as Arthur Rimbaud, Stéphane Mallarmé, Max Jacob, and Francis Ponge.

In the last fifty years or so, American and, to a lesser extent, Canadian poets have also taken up prose poetry with enthusiasm. Writers such as Russell Edson, Maggie Nelson, Anne Carson, Mark Strand, Maxine Chernoff, Peter Johnson, Lyn Hejinian, and Charles Simic – whose prose poetry collection The World Doesn’t End (1989) won a Pulitzer Prize – have given the form prominence. Claudia Rankine has written highly distinguished prose poetry and Canadian poet Eve Joseph’s Quarrels (2018) won the Griffin Prize. Today, much of the genuinely experimental poetry by Anglophone writers is being written by prose poets.

In Australia, too, there has been an often unacknowledged burgeoning of an innovative prose poetry over the last half century. This rise is evidenced by the high quality and diversity of the inclusions in the Anthology of Australian Prose Poetry (2020), and it is also demonstrated by the volume being reviewed.

Gary Catalano was a consummate Australian poet, art critic, and short fiction writer who died aged only fifty-five in 2002. He mostly wrote fairly brief lineated poems and prose poems, publishing books which often mixed both forms. His lineated poetry is highly accomplished, and although he never quite fitted into the dominant, often combative poetry cliques of his period, his work has a secure place in Australian literary history.

In many cases, his prose poetry represents the best of his writing, and it is gratifying that Des Cowley has now edited a volume of Catalano’s collected prose poems. Reading these prose poems together not only confirms the strength of Catalano’s poetic voice but also demonstrates their powerful connections, especially in terms of imagery and technique. They are informed by a broad knowledge of culture, particularly Australian and European visual art, and with important ideas about human conduct and judgement.

It is unusual in Australia for a poetry book to be published with such fastidious attention to the layout of poems and the overall design of the volume. Every prose poem has its own double-page spread – even the shorter works – and the generosity of white space allows Catalano’s works to breathe and expand. This complements the artfulness of his language and of the prose poem form. He constructs richly complex sentences and paragraphs that appear to unfold effortlessly as they cluster, aggregate, create and release tension, and harness particular rhythms – while also allowing convincing shifts in perspective.

These prose poems combine sharp, detailed observation with a powerful sense of the quotidian’s strangeness. For instance, a prose poem entitled ‘Quotidian’, begins: ‘Yes. That the day was an ordinary one can be proven by this one fact: there were no fat men in the trees.’ As Catalano comments on the stereotype of ‘philosophic figures, somewhat sad of visage, who inquire into the meaning of things’, it is evident that his purpose is parodic. Yet the prose poem has a serious dimension, too, asking the reader to consider what an ‘ordinary’ day might actually be, and how we make meaning from what we know.

More generally, Catalano’s prose poems often refer to everyday encounters and familiar objects. He writes of driftwood, an incinerator, a dump, a cupboard, fruit, birds, waves, and stones – all things that may be seen, touched, or held. The prose poems possess a disarming combination of directness and obliquity, and are consistently inventive in their use of figurative language, often for the purposes of defamiliarisation. For example, in ‘Silver and Gold’, breaking waves have ‘the sound of a hand sifting through a bag of grain’. There is, too, a recursive quality to some of these works, as prose poems accumulate related detail, or return with a modified perspective to where they started.

Importantly, there is also a neo-surrealistic quality inhabiting many of these works. This is different to the surrealism of twentieth-century European prose poets and also gentler than the neo-surrealism employed by American poets such as Edson or Simic. However, Catalano was presumably aware of such examples and many of his works have a dream-like strangeness that challenges conventional understandings and perceptions and sometimes create notional scenarios. An example is the short poem ‘Incidents from a War’:

When the enemy planes flew over our city they disgorged notbombs but loaves of bread. Can you imagine our surprise? Weventured outside after those planes had disappeared from thesky, and what did we find there but heaps of broken bread atwhich the pigeons were already feeding?

This prose poem shows Catalano’s liking for imagist techniques; many of his works are like verbal paintings or photographs. Indeed, the openings of his prose poems frequently convey a sense of the writer framing a scene and inviting the reader to join him in examining it. Examples are: ‘A room at night, a room in which the curtains are stirring’; and ‘In a country far from here a young boy stands beneath a mulberry tree’.

In showing the reader so convincingly how weirdly ordinary and how strangely familiar the world may be, Catalano is arguably Australia’s most successful and distinguished twentieth-century prose poet. He is one of few poets in this period to write extensively in this form and to demonstrate a sustained capacity to extend prose poetry’s boundaries. Even his slighter works repay close reading. These prose poems are undemonstrative and consistently illuminating, opening new pathways in their insistence on the value of poetry written in prose. This important volume reminds readers that poetry comes in various, sometimes unexpected forms and should be celebrated accordingly.

Comments powered by CComment