- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The aversion of conformity

- Article Subtitle: A genre-frisking collection

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Charles Bernstein, born in 1950, is a prolific poet and theorist of Language poetry, which arose in the 1970s in the wake of the anti-Vietnam War movement (or the American War, as the Vietnamese call it). As with similar movements in many countries, including Australia, this now semi-institutionalised poetry began as radical revolt against an established verse culture that preferred its poetry to be an easily palatable, Inauguration-worthy commodity. Instead, Bernstein and his colleagues variously practised a ‘multi-discourse text’ that chipped away at the boundary between poetry and critical theory. ‘Poetry is the aversion of conformity,’ Bernstein writes in an early essay, rephrasing Ralph Waldo Emerson. It is a site of perpetual enquiry rather than the expedient repose of fixed meaning.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Charles Bernstein (photograph via the University of Pennsylvania)

- Alt Tag (Article Hero Image): Charles Bernstein (photograph via the University of Pennsylvania)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Gig Ryan reviews 'Topsy-Turvy' by Charles Bernstein

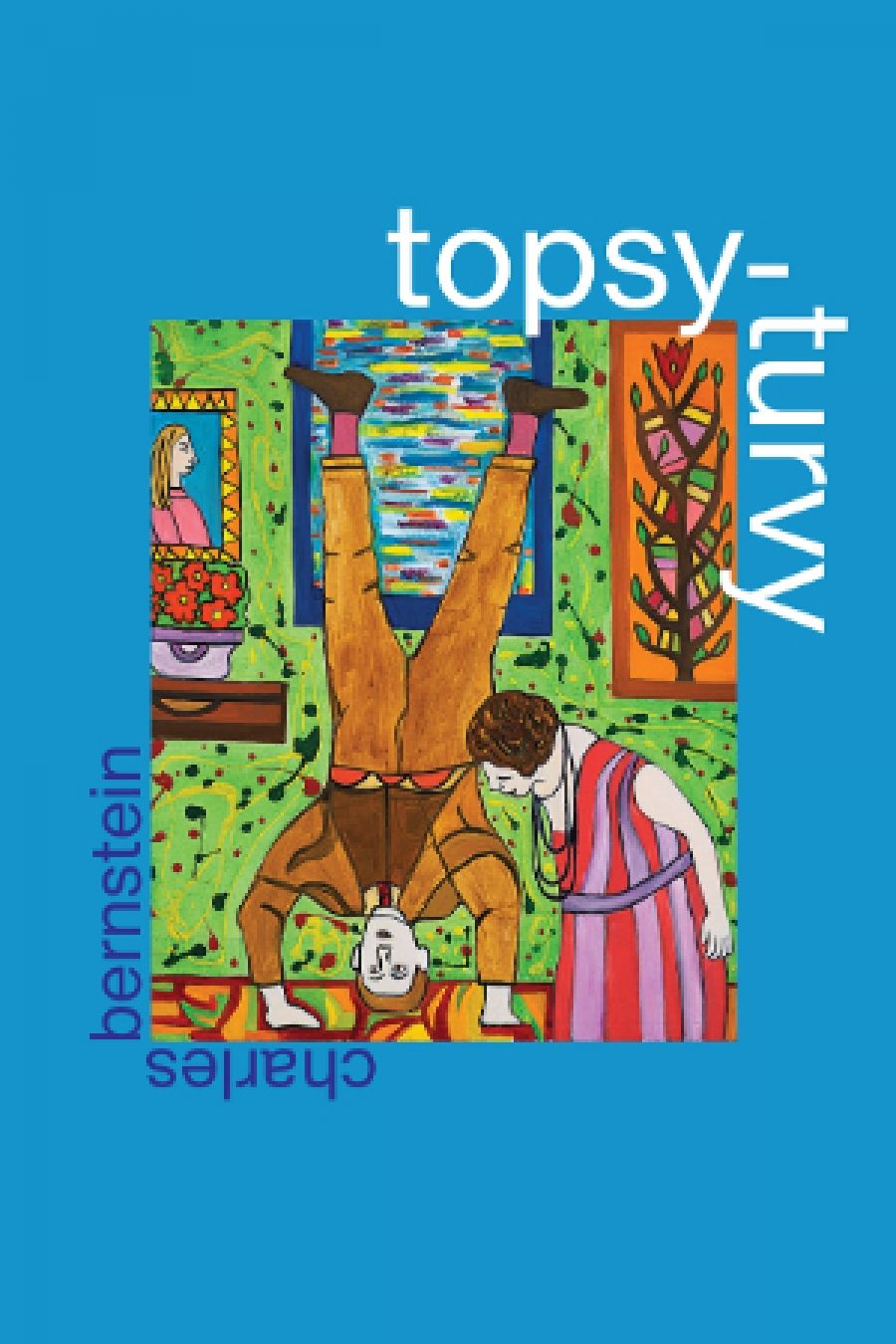

- Book 1 Title: Topsy-Turvy

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, $41.95 pb, 170 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/XxZL5X

My mind’s abind in double and thriple blinds

Scarcely can I see what’s right in front of me

I stumble and stare at things no longer there

My head’s in the hopper, unscrambled by doppler

The planet is warming but not to me ...

What happened to disjunction, parasols, and ennui?(‘The Wages of Pascal’)

He encourages what he calls ‘dysraphism’, a mis-seaming of the poem that repels soporific absorption.

Topsy-Turvy, Bernstein’s nineteenth book of poetry, is divided into four sections: ‘Cognitive Dissonance’, ‘As I love’ (title from Louis Zukofsky’s “A”), ‘Locomotion’, and ‘Last Kind Words’, a blues song by Geeshie Wiley that is also the book’s epigraph. Topsy-Turvy mashes up adages, quotations, questionnaires, interviews, rough-cut rhythms such as ‘Covidity’, and both real and imaginary translations. As in previous books, Bernstein frisks any genre for potential, simultaneously mocking and respecting each constraint:

Confide only in friends from past five years ... Signs of compatibility include sudden rain, heightened gait, and tender elbow. High risk of falling into dark matter ... Preferred alcohol: Trappist brandy (spritz).

(‘Twelve Year Universal Horoscope’)

Some poems simply answer a poem’s title, such as ‘A Unified Theory of Poetry’, the poem being ‘I don’t think so.’ Bernstein rips up poetic decorum and dismantles any clingy lyricism through clunky rhymes that require the reader to refocus away from expected musicality to the poem’s faktura, to question what poetry can be by exaggerating what is absent. ‘Content can never equal meaning,’ he writes in A Poetics (1992), veering from Robert Creeley’s ‘Form is only an extension of content’. Some poems are layers of dialogic arguments and corrections, juxtaposed with a comic glee that obscures their subversiveness. ‘My father would be a yarn salesman’ is a drumroll of the famous (mainly men) that partly ridicules the banal categorising of pop psychology: ‘Annibale Carracci is a narcissist / Bacon is riddled with riddles / Dowland is a real human being / Marlowe is heartless / Shakespeare is delusional / Galileo has a Jewish cast of mind / Caravaggio is not emotional enough.’ Statements qualify each other to constantly reframe the poem, which is itself thinking, and so can never conclude.

For Bernstein, poetry is innately fluid, hypertextual, always an encountering, a ‘becoming’, as Heidegger and Schlegel theorised. If seriousness is sought, comedy will follow, and vice versa. His borrowings satirise the misty sanctification draped over the originals: ‘We were / the fire before / the fire was / ours. Now it’s / theirs’, (‘The Gift Outright’). Mallarmé’s hallowed ‘Un coup de dés’ is scrambled in ‘Theory of Pottery’, as also in earlier poems, thus subtly proposing an alternative poetics:

... Better hung out to dry than be

buried alive. Fancy is

at the root of illusion and the soul

of truth. – A kick in the ass will never

abolish asses.

Collaboration also undermines traditional authorial voice: hence the interviews and discussions that are equally poems. ‘Echologs’, co-written with Richard Tuttle, is a spirited modernising of the poetry match in Virgil’s ‘Eclogue 3’: ‘Those abide prize crap adore boring poems, / watch them milk jackasses and water stones.’ Strewn with allusions and recraftings from Milton to Rimbaud to William Carlos Williams to the Bible, Bernstein’s echo-poetics drag each poem across a rubble of erudition, just one example being ‘No then there then’, which sounds like Gertrude Stein, but is from Augustine’s Confessions (11.13.15), imagining that time would not exist without God, its creator.

Bernstein has published and edited countless essays and translations, as well as co-directing PennSound, a massive archive of poetry readings and interviews. It is hard to thresh the poems away from his swarm of affably directing essays, or to appreciate some poems without fully acknowledging the history they dissect. As lively and polyphonous as his poems, the essays also reel with aphorisms, puns, and scathing humour, such as the itemising of The New Yorker’s bland ‘water’ poems in My Way, or the jeremiads of ‘Recantorium’ in Attack of the Difficult Poems (2011) that recant his own methods as being ‘contrary to the Books of the Accessible Poets’, or his amusement at non-poets confidently judging poetry because they too are ‘human’. Difficulty to Bernstein is not an obstruction to apologise for, or to, but a furthering of possibility: ‘Innovation is not so much an aesthetic value as an aesthetic necessity’ (Attack of the Difficult Poems). Sometimes the jollity that defenestrates canonical works is more feeble slapstick than aesthetic assault, but even these incursions are elegiac, preserving while debunking. Along with actual elegies (including one to Sean Bonney), Topsy-Turvy’s cross-currents of the upheavals of Covid-19, the instabilities of migration, translation itself, each implies distance and loss. In Bernstein’s continuing tug between lyric song and radical polemic, there is an irrepressible inventiveness that simmers over savagery of intent:

The enemy of my enmity is my calamity.

COMMENTARY: Don’t say “I told you so” until you’re wrong.

COMMENTARY: Indignation intensifies heartburn but is preferable to heart failure.

COMMENTARY: The enemy of my enmity is my sentimentality.(‘Swan Song’)

Comments powered by CComment