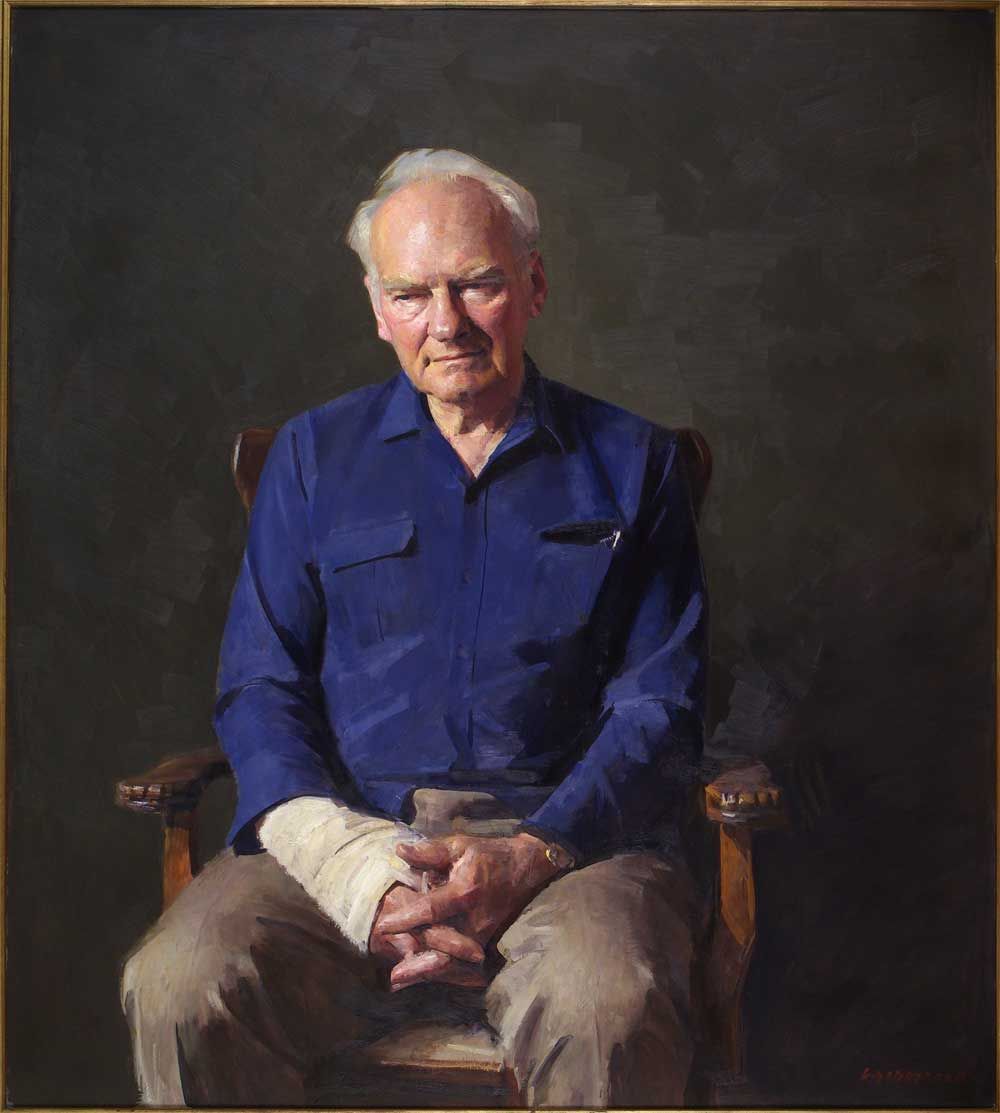

Hugh Stretton knew he was a lucky man – someone born well in the lottery of life. Born in 1924, he came into a thoughtful family with a strong record of public service. He was educated at fine private schools and excelled in his arts and legal studies at the University of Melbourne. When war intervened, Stretton served in the navy for three years without suffering injury and then won a Rhodes scholarship before completing his undergraduate qualifications.

The golden thread continued at Oxford. He was a student so clever he was awarded a college fellowship before taking his final exams, a scholar so magnetic he was offered the Chair of History at the University of Adelaide before he turned thirty, though he had neither a doctorate nor a book to his name.

Stretton returned to Australia the youngest professor in the nation, took on a role in which he excelled, developed new interests in city planning, and became a valued adviser to governments and oppositions. Within two decades, Stretton was presenting the Boyer Lectures (Housing and Government, 1974) and had become, in Peter Beilharz’s words, ‘widely recognised as Australia’s leading democratic thinker’.

When in 1968 the administrative burden of being Chair of the Department of History became too much, Stretton simply demoted himself to Reader so that he could focus on teaching and writing. He donated all the royalties from his most successful book, Ideas for Australian Cities (1970), to the Brotherhood of St Laurence to support its charitable work. At the Brotherhood, he began a friendship with Barry Jones, a future science minister in the Hawke government, that would endure for decades. A collection of their correspondence is now held by the National Library of Australia. Yet, says Graeme Davison in his perceptive introduction to Stretton’s Selected Writings (2018), throughout a long and active public life Stretton remained modest, self-deprecating, and generous ‘almost to a fault’.

We each respond to luck in ways that reveal our underlying character. Good fortune invited Stretton to reflect on his values. Since education opened up opportunities for him, Stretton wanted others to enjoy the same privilege. He advocated urban planning that avoided sharp class barriers, and public spaces which encouraged people to mix, as he mixed with men from very different backgrounds during his time below decks in the navy.

A tenured academic, Stretton wanted more jobs with security so that Australians could build lives not blighted by capricious economic disruption. A practical man, he did not seek to remake cities – or societies – with a wave of the hand, but rather to build on what already worked well. Stretton preferred pragmatism over ideology, experiment over economic orthodoxy. He valued culture with emphasised solidarity in a political system that ‘encourages individual difference and non-conformity’. This eminent public thinker refused to be typecast, variously describing himself as a ‘moderate socialist’ or a ‘radical conservative’.

The University of Adelaide was far-sighted in recruiting young Hugh Stretton in 1954, as it is wise now to establish a policy shop in his name. In interests and range, the Stretton Institute will no doubt reflect on the question which always shadows good fortune: when life is generous to me, what is my responsibility toward those for whom fate has not been so kind? For birth is the great gamble. We take a ticket and are born into bodies, families, health, and societies we do not choose. A random roll of the dice can shape an entire life – into love and security, as Stretton experienced, or into hardship and poverty. Life can be non-linear and our fates arbitrary.

This inescapable lottery imposes a moral challenge. Our starting points are inherently unequal. Some enjoy privilege while others struggle. Birth is always a lottery – must life be one also?

It is hardly an original question. Making sense of chance in life has been a preoccupation of religion and philosophy for millennia. For a democratic thinker, poverty poses a dilemma. What do we owe our fellow citizens who suffer deprivation? We expect government to address economic distress, but we, the voters, also put firm boundaries around our generosity. Much is left to charity, or seen as essentially a private concern, outside political discussion.

Millions of Australians accept a responsibility to help those facing difficulty. Some eighty per cent of adult Australians make charitable donations each year, and many invest time helping charities and voluntary organisations. Yet charity will always struggle on its own. It can never command the resources required to deal with entrenched disadvantage.

We have a fond image of Australia as the land of the fair go, the place where hard work, determination, and talent allow people to find their way in the world. And so it proves for many. Yet the scale of disadvantage in our community remains confronting. The most recent available data reveals that 3.24 million Australians live below the poverty line. This represents more than thirteen per cent of the population, including 750,000 children. Australian levels of poverty are slightly above OECD averages, and have changed little over the past decade. The cost of housing, declining incomes, and modest benefit payments are key drivers.

Particularly at risk are single parents, recent migrants and refugees, Australians living alone or outside a major urban area, people emerging from the criminal justice system, those with minimal education qualifications, and people on social security benefits, such as the elderly. Disability has been a persistent marker of disadvantage, linked to limited employment, housing, and transport options.

Above all, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians face poverty levels almost double that experienced by other Australians. It is more than two centuries since European settlement, yet across this nation the descendants of the First Australians remain those most likely to experience economic hardship – a compelling reminder that poverty is often intergenerational, a cycle that proves difficult to escape.

To express disadvantage through numbers conveys nothing of the lived reality. A static picture provides little feel for patterns. So let’s start from a different point: if you are born into one of the poorest households in Australia, what are your chances of breaking out, of achieving a more prosperous life as an adult? Can we predict likely outcomes for young children born into poverty?

Sadly we can. A detailed 2020 study by the Melbourne Institute confirms that most children born into extreme economic disadvantage struggle to prosper in adulthood. On average, the more years a child spends in poverty, the worse their likely socio-economic outcomes. A child from an impoverished background is five times more likely to suffer adult poverty. In this meritocratic society, entrenched poverty is handed down from parent to child, and social mobility highly constrained. For more than one in ten Australians, a lifetime of economic struggle beckons.

It is easy to look away, to accept the world as we find it. Yet how we respond to misfortune in our midst says everything about us. Ethicist Peter Singer speaks of an obligation to assist. If we encounter a child drowning in a pond, says Singer, we should put aside concern for our clothes and swim to the rescue, because the harm we can avert is so much more important than the cost to ourselves. Singer expresses this as a simple principle: ‘If it is in our power to prevent something very bad happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it.’

The caveat about ‘comparable moral importance’ is important. Our obligation to others is not an absolute moral imperative but a judgement about consequences. If responding requires us to be unjust to others, or to accept an unreasonable burden, then the calculation shifts. But if the cost is small in comparison to the difference we can make, our responsibility is clear. Singer believes the requirement to assist applies ‘not just to rare situations in which one can save a child’ but also to helping those who live in extreme poverty. If an affluent society can help, it should.

This turns a philosophical point into an issue of public policy. The Australian settlement never pursued a radical redistribution of wealth. Social benefit payments remain modest. The Henderson poverty line, first published in August 1975, made clear that even with child endowment and other benefits, some Australian families could not achieve a reasonable standard of living.

Of course, Australians have never demanded their governments solve the challenge of disadvantage. Almost every election is a referendum on how much tax we are willing to pay, and the answer is usually the same. We seek a trade-off between helping others and limiting demands on ourselves. Our electoral decisions limit the scope open to any government. This means we expect much from charity in mitigating life’s lottery.

Individual Australians donate more than $12.5 billion annually to support everything from child protection and emergency relief to programs for refugees. Business contributes a further $17.5 billion annually in charitable donations. We support some 56,000 registered not-for-profit organisations across the nation, employing more than 1.3 million Australians part- and full-time. Yet, apparently impressive figures can mislead. Overall, charitable income remains small compared to government. Combined state and federal spending on education, health, and welfare dwarfs the resources available to charities. Government remains the most significant player in addressing disadvantage, leaving the charitable sector perched around the edges of public investment. Which leaves something of a dilemma: if charity is too small, and government too limited, can anything change the equation for those who draw a blank in the lottery of life? How do we meet an obligation to assist if charities lack the money and governments lack the appropriate design, local engagement, and commitment to provide viable pathways from disadvantage?

Yet there are some reasons for quiet optimism. Promising projects can redraw the separation between government and charity. What happens if communities and government agencies, charities, and foundations combine their intelligence and resources around an agreed goal? There are encouraging examples of collaboration in practice, such as helping children prepare for and succeed in school. This addresses a trap that leaves people otherwise unable to escape the cumulative effects of poverty. Collaborations between community, government, and charity can provide an ‘off-ramp’: a way to help people step outside the endless repetition and setback of a cycle of disadvantage.

For government, collaboration can be daunting. Public agencies must deploy standardised approaches and treat everyone equally, though every disadvantaged person lives with different personal circumstances. Charities know more about possible off-ramps, but they rarely command enough money or people to tailor programs appropriate for each individual or family.

Put the two approaches together and new possibilities open. In an ideal setting, pre-school and education support, health services, and transition-to-work programs, whether provided by government or charity, would be linked so that a child at risk has consistent encouragement and support all the way through to adult life. Such an integrated service would be based locally so that individual needs and aspirations are heard. It would ensure continuity of friendly faces and understanding through the journey.

This is the approach adopted by Our Place, a Victorian initiative which began at Doveton College in 2012 and which now extends to ten sites across the state. Using a local primary school as the hub, Our Place coordinates service delivery for children and their families in disadvantaged communities. It has inspired relevant government departments to pool their expertise, and foundations to make long-term funding commitments.

One Our Place facility involves a partnership between the Carlton Primary School, the City of Melbourne, and the Carlton housing estate. The school sits adjacent to public housing, a pocket of disadvantage in an otherwise affluent suburb. Only two per cent of students at the school come from English-speaking backgrounds. This is a linguistically and culturally diverse gathering of migrants and refugees in one community, sharing ageing buildings which were locked down – with the residents inside – in July 2020 because of Covid-19.

Investment by the state government includes a former school building refurbished to provide education facilities and funding for an early learning service, community spaces, health consulting rooms, and a mother and childcare service. Gowrie Victoria operates the early learning centre, while the YMCA offers after-school activities, all linked by a dedicated community facilitator.

The Our Place model argues that programs should focus not just on children but also on their families. Attention is paid to adult education, recognising that getting unemployed parents into work brings broader benefits for their children. Our Place calls this ‘reshaping the service system’ to provide wrap-around support.

Well-led partnerships transform lives. This collaborative approach has a name: collective impact. It suggests the best chance of social change is when communities, government, and for-purpose organisations work towards a shared goal. Collective impact requires a common agenda, a shared measurement system, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous dialogue, and a backbone organisation.

Collective work imposes uncomfortable demands on everyone. Communities are asked to acknowledge and take ownership of local problems. Government agencies are expected to collaborate, pool funding, and work to someone else’s priorities. Local business must accept a role in securing outcomes for the neighbourhood. Collective impact demands charities and foundations be patient, while community leaders and their public agency partners experiment, fail, and then fail better.

The collective impact model has an established history across Australia with programs such as the Cape York Partnerships and the empowered communities movement. The approach has inspired place-based initiatives, including Logan Together in south-east Queensland and the Hive at Mt Druitt in Sydney. It guides Adelaide Zero, a project to end homelessness in the inner city.

Policy innovation should not end with collective impact – not every problem is based in a community, or amenable to collaborative responses. There are other significant responses worth considering, including social impact investing. This raises and deploys private capital for ventures which combine some profit with social outcomes. The Aspire Social Impact Bond is Australia’s first social impact program with homelessness as its primary focus. It aims to generate a competitive financial return while ‘making a lasting difference to the lives of people experiencing homelessness in Adelaide’.

We need all these innovations, and so many more. In the tradition of Hugh Stretton, we should welcome policy experiments which build on what works. Policy is never final, but a series of continuous tests and occasional improvements guided by experience and evidence.

That poverty endures despite much public and private investment, despite people and agencies committed to its eradication, despite generations of social science research and policy proposals, points to the implausibility of swift solutions. We know what failure looks like – think, sadly, of our national inability to ‘Close the Gap’. Yet we can hope that a process which begins with community voice and goes on to ask individuals and communities, charities, businesses, and foundations to work as partners might provide new off-ramps to address disadvantage.

Australians are inventive and independent. Those living with disadvantage want change, not charity. Give people a viable off-ramp and they can take control of their lives. Cycles of disadvantage are dogged and entrenched but not impervious. And when existing policy does not solve the problem of intergenerational poverty, new thinking is essential. Thinking from public intellectuals such as Stretton, from everyone committed to better outcomes. A nation that saves its people from calamitous health outcomes and deploys vast reserves to soften economic distress can also address poverty. Community, charity, and governments, working together, can succeed where each alone will falter. Our responsibility for others remains compelling. The lottery of life means some people will be born and die, whatever their merit or talent, without sufficient opportunity for dignity and fulfilment. The measure of justice is whether our society empowers individuals – you, me, everyone – to find the life we want.

So the challenge is entirely our own. One of the richest societies on the planet once stared down a global financial crisis and now protects its population from a pandemic. Such a nation can end poverty among its own citizens – if it chooses. The effort needs a grand coalition of community, charity, and government. It requires a tolerance for failure, an ability to recognise and celebrate success. Waiting in a myriad of experiments, of small local victories, are the models that can work.

We start as helpless participants in a blind lottery. Let our beginning not also prove to be our end.

This is an edited version of the Inaugural Hugh Stretton Oration, delivered at the University of Adelaide on 18 February 2021. It draws from Glyn Davis’s On Life’s Lottery (Hachette, 2021).