- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘At the Cannon’s mouth’

- Article Subtitle: Alfred Deakin’s enterprising daughter

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Vera Deakin was Alfred and Pattie Deakin’s third and youngest daughter. Born on Christmas Day 1891 as Melbourne slid into depression, she grew up in a political household, well aware of her father’s dedication to the service of the Australian nation, not only in the Federation movement but later as attorney-general and three times as prime minister.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Vera Deakin Red Cross

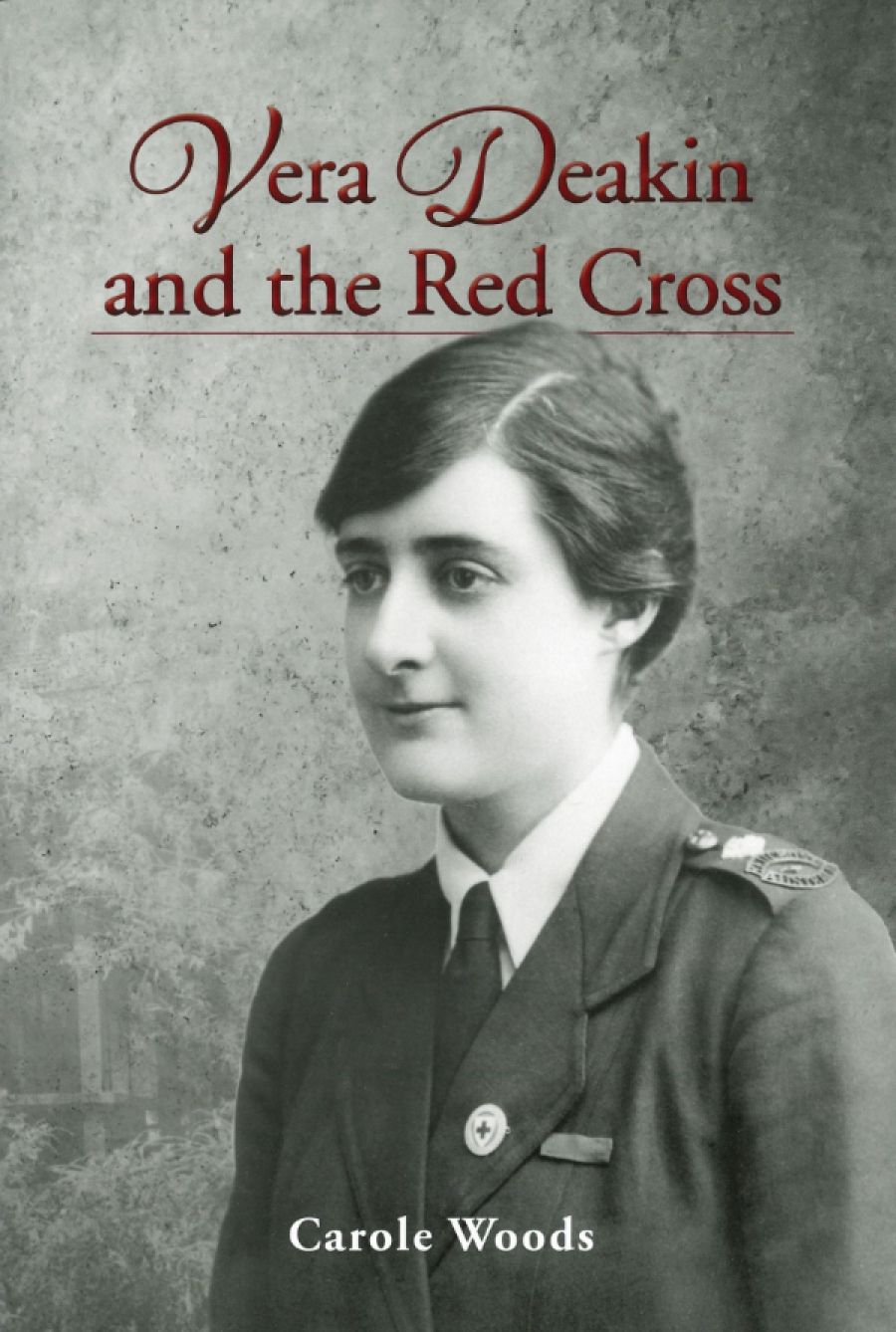

- Book 1 Title: Vera Deakin and the Red Cross

- Book 1 Biblio: Royal Historical Society of Victoria, $35 hb, 244 pp

Alfred’s sister Catherine, who was an accomplished pianist, oversaw the girl’s early education, including in music. When she was twenty-one, Vera went to Europe, accompanied by her aunt, to pursue training in voice and cello, first in Berlin and later in Budapest. Vera wrote long letters home, full of detailed descriptions of their daily lives, the concerts and operas they attended, the sights of middle Europe, and the changing of the seasons. The letters are charming, and Woods makes good use of them. Vera and Catherine were travelling back to London when war was declared; Vera was swept up in the patriotic fervour that accompanied its outbreak.

The Great War was the defining event of Vera’s life, as it was for so many of her generation. She was keen to contribute and railed against the expectation that her contribution would be knitting socks and balaclavas for the soldiers and serving them refreshments, as her mother was soon doing at the Anzac Buffet in Melbourne. ‘Why aren’t women who have no real ties of duty standing at the Cannon’s mouth shoulder to shoulder with the men?’ she wrote to her parents.

Back in Australia, Vera explored her options. In 1915 she and a friend, Winifred Johnson, went to work at the Red Cross in Egypt, where a relative was one of the commissioners. Her decision and her capacity to act on it were enabled by her family’s connections and financial support, as well as by her cultural capital. After all, not many twenty-three-year-old Australian women had already been abroad twice.

Confident, smart, and extremely capable, Vera, with Winifred, established the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau in Egypt. A year later, the Bureau was transferred to London where Vera ran it until 1919, when she returned to Australia to be with her family as her father slid towards his death that year. She managed a staff of around thirty, all volunteers with a predominance of Australian women, who responded to enquiries from distressed relatives on the basis of information gleaned from official sources as well as by searchers visiting hospitals and talking with soldiers about their mates’ last moments. The sympathetic letters of Bureau staff gave context and detail compared with the stark military notifications of ‘Wounded’ or ‘Missing in Action’. It was a prodigious organisational challenge. For example, in 1917 the Bureau received 26,953 cables from Australia and sent 24,610 replies. Vera rose to the challenge, displaying a remarkable talent for efficient, effective administration. We know a great deal about men’s experiences of the terrible years of World War I, but far less about women’s, especially the work of volunteers like Vera Deakin. Woods’s account of her work at the Bureau is fascinating.

Vera and her Australian friends also provided friendship and hospitality to Australian servicemen on leave in London, some of whom they knew. At the end of 1918, she met Captain Thomas White, an Australian pilot who had escaped from Turkey, where he had been a prisoner of war. Three weeks later they were engaged. It was the beginning of a happy and productive partnership, with a shared dedication to commemorating the sacrifices of their generation, a mutual love of the British Empire, and the joy of four daughters. White went into federal politics, and when war broke out again in 1939 he enlisted. Vera White, as she then was, contributed her experience and organisational prowess to the enquiry work of the Victorian Red Cross. Later, she and Tom lived in London after Robert Menzies appointed him high commissioner.

Vera Deakin White’s life was in some ways a conventional middle-class one, and in others much more as she found ways to use her intellect and energy productively in fields beyond the home. She was an Australian-Briton, an empire loyalist at home in London and bewitched by the English countryside, but she was often homesick for the Australian summers and the beach at Point Lonsdale. She inherited her parents’ beach house, Ballara, at Point Lonsdale, and her grandchildren still enjoy its tranquillity.

Though some of the chronology could have been more smoothly handled, Carole Woods has written an engaging biography of a middle-class Australian woman who used her talents and her family connections to live a useful and productive life of which her father would have been proud. Vera Deakin and the Red Cross, published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria, is very handsome, easy on the eye, and well illustrated, making it a perfect gift.

Comments powered by CComment