- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Trapped in a desert’

- Article Subtitle: Fire and soul in African American poetry

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Library of America has published massive anthologies of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American poetry that include work from multiple racial and ethnic backgrounds, so why now another large book devoted exclusively to African Americans? Because it needs to be said and said again just how profoundly American this poetry is, how it enriches culture and should not be ignored among the more conventionally canonised. The fact that this book appeared in 2020, the year when Black Lives Matter protests went global, only underlines its importance as a historical marker. Poetry by Black Americans is not only unignorable but central to American literary life. Reading African American Poetry: 250 years of struggle and song may change your way of reading poetry, particularly modern poetry. It is that rare thing among anthologies, a moving book, enlivened by fire and soul.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): African American Poetry

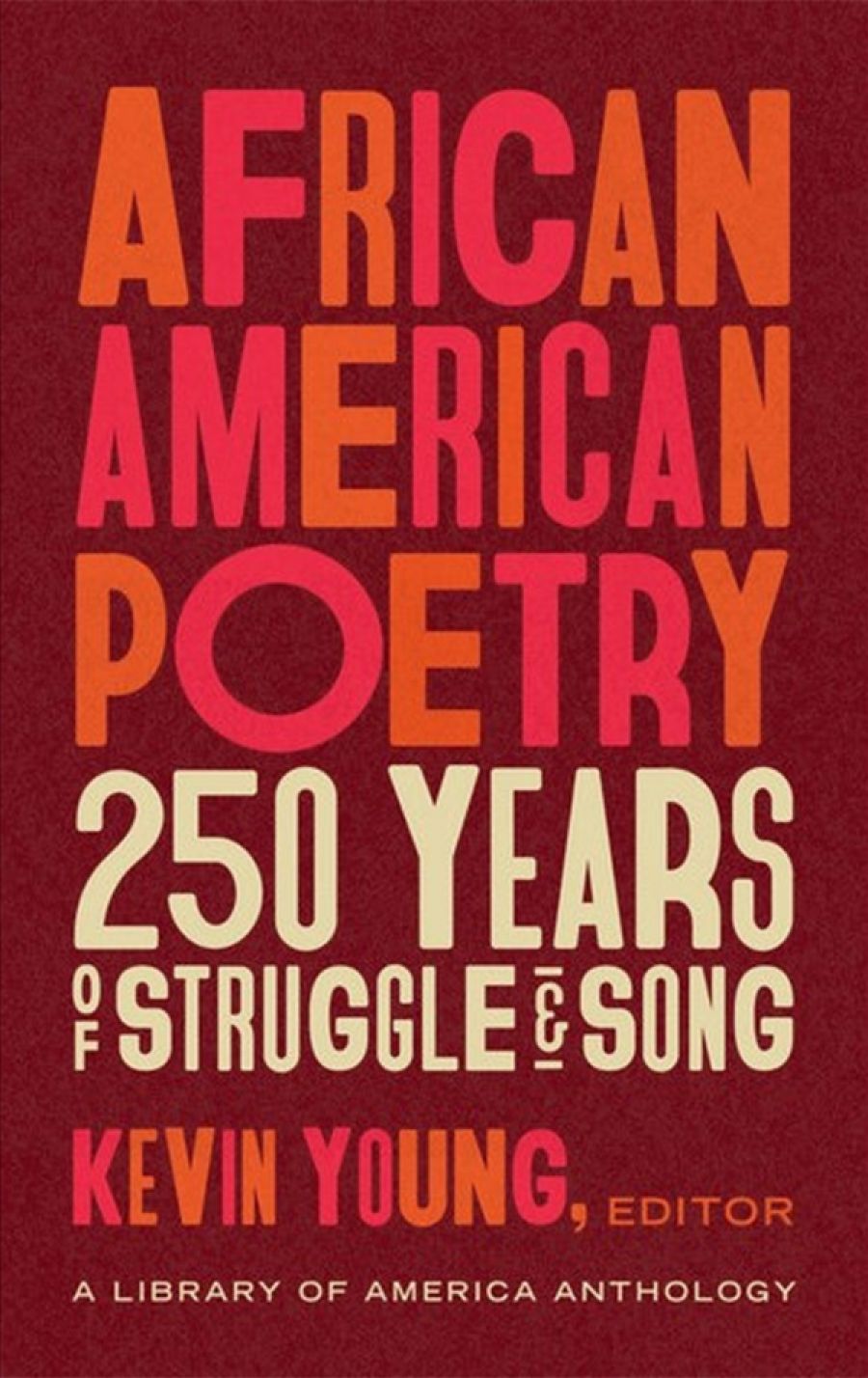

- Book 1 Title: African American Poetry

- Book 1 Subtitle: 250 years of struggle and song

- Book 1 Biblio: Library of America, US$45 hb, 1,150 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/n1LD06

The editor, Kevin Young, is himself a prominent poet, currently poetry editor of The New Yorker, and a man devoted to historical reclamation. Most readers will find poets in these pages they have never heard of before, mixed in with giants like Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Derek Walcott. If a poetics of identity and social justice predominates, that is only natural, given the violent history of slavery, civil war, lynchings, beatings, and police shootings, not to mention Black on Black violence. We find police shootings of young Black men in the poetry of Sterling A. Brown (1901–89): ‘The Negro must have been dangerous, / Because he ran; / And here was a rookie with a chance / To prove himself a man.’ And we find the subject later in Audre Lorde (1934–92): ‘I am trapped in a desert of raw gunshot wounds / and a dead child dragging his shattered black / face off the edge of my sleep.’ And again in newer poets like Jericho Brown (1976–), winner of the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, whose sonnet ‘The Tradition’ begins in pastoral mode by naming flowers and ends by naming the dead. And still more recently, Hanif Abdurraqib (1989–) asks in a title, ‘How Can Black People Write about Flowers in a Time Like This’, yet proceeds to write about flowers anyway. His poem derives its beauty from the immense pressure of history.

Black poets do not write only about violence, of course, and identity poetics is a field as rife with controversy as any other. Witness the legacy of terms like ‘Negro’ and ‘African American’, with or without the hyphen. The problem of manners and nomenclature presses upon us: what are we to call people without causing offence? ‘Black is an open umbrella,’ wrote Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), her eye on a global identity. ‘I am a Black and A Black forever’. She added, ‘We are graces in any places’ and ‘I am other than Hyphenation.’ Identity is sometimes pressed upon us whether we want it or not – perhaps a universal condition in our time.

This anthology begins with Phillis Wheatley, who was born in Africa sometime around 1753 and brought to America as a slave. She became literate and was only about twenty when she published Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). Her paeans to imagination and memory constitute textbook Enlightenment verse. She was not alone among American poets in having to be published first in England – both Anne Bradstreet and Robert Frost faced the same problem. And she was not alone among women poets in suffering neglect. She died soon after giving birth and was buried in an unmarked grave. It seems particularly galling that her poem ‘To His Excellency General Washington’ makes no mention of the great man’s slaves.

Young divides his book into eight historical periods, organising his poets alphabetically within later sections, allowing both a helpful sense of chronology and fortuitous groupings of disparate talents. Many of the early poets might fit comfortably among white writers from, say, the Hudson River School, with its pastoral leanings, but outrage at slavery and the rise of abolitionism figure more prominently. Ann Plato (c.1824–70), who was part Native American, writes of ‘how my Indian fathers dwelt’ and how they ‘sore oppression felt’. James Madison Bell (1826–1902) befriended the abolitionist John Brown and, according to the biographical notes, ‘raised funds for Brown’s 1859 raid on the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia’. His ‘Song for the First of August’ praises the British abolition of slavery in 1834, reminding compatriots that America was far too slow to follow the example.

The book really heats up in its second section when it hits the twentieth century. Here we find familiar figures like W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and James Weldon Johnson, but also Angelina Weld Grimké (1880–1958), a beautiful poet who never published a book. Her lyrics, such as these from ‘A Mona Lisa’, seem the soul of lyricism: ‘Would my white bones / Be the only white bones / Wavering back and forth, back and forth / In their depths?’ Another poem, ‘Trees’ prefigures Abel Meeropol’s ‘Strange Fruit’ (made famous by Billie Holiday) in its depiction of lynching.

Part Three of the anthology deals with the Harlem Renaissance, in which Grimké also played a part. The Chicago Renaissance follows in Part Four, though the section includes figures as diverse as Gwendolyn Brooks, Robert Hayden, Melvin B. Tolson, and Richard Wright, whose title ‘Between the World and Me’ has recently been recalled in a bestselling book by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

How in a brief space to convey the riches that follow? Caribbean poets like Derek Walcott, Kamau Brathwaite, and Lorna Goodison, all of whom have connections to the United States; Black Arts poets like Amiri Baraka, represented here by tender early lyrics and a later poem marred by anti-Semitism; spoken-word artists like Gil Scott-Heron; and a range of writers including Michael S. Harper, Quincy Troupe, Rita Dove, Marilyn Nelson, and Yusef Komunyakaa. We have the dramatic monologues of Ai, the exploded sonnets of Wanda Coleman, the fine work of Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady, who co-founded the influential poetry collective Cave Canem. We have Nigerian-born Chris Abani, an exuberant chant-poem by Alison C. Rollins, the chastening prose of Claudia Rankine, accomplished establishment figures like Tracy K. Smith and Natasha Trethewey, and the engaging work of Ross Gay, Terrance Hayes, Major Jackson and Tyehimba Jess – work increasingly recognised by prizes and professorships.

Not all of it is equally good, of course. The Library of America anthologies are historical surveys more than primers in the art. Drawbacks to this volume are few: more song lyrics might have been included, and the biographical notes are thin. But why quibble with a major contribution to the human race?

Comments powered by CComment