- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Teeming leeches

- Article Subtitle: The perils of experimentalism

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Experimental writing’ can sometimes seem like a wastebasket diagnosis for any text that defies categorisation. Even when used precisely, it begs certain questions. Isn’t all creative writing ‘experimental’ to some degree? Isn’t the trick to conceal the experimentation? And what relationship does it bear to the ‘avant-garde’? If avant-gardism implies a radical philosophy of art, where does ‘experimentalism’ fit today? Is it not part of the valorisation of novelty, of innovation for innovation’s sake, which has gripped the literary establishment in recent decades? (When books like Milkman [2018] and Ducks, Newburyport [2019] fall victim to the cosiest of literary prizes, where have the real radicals gone?)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

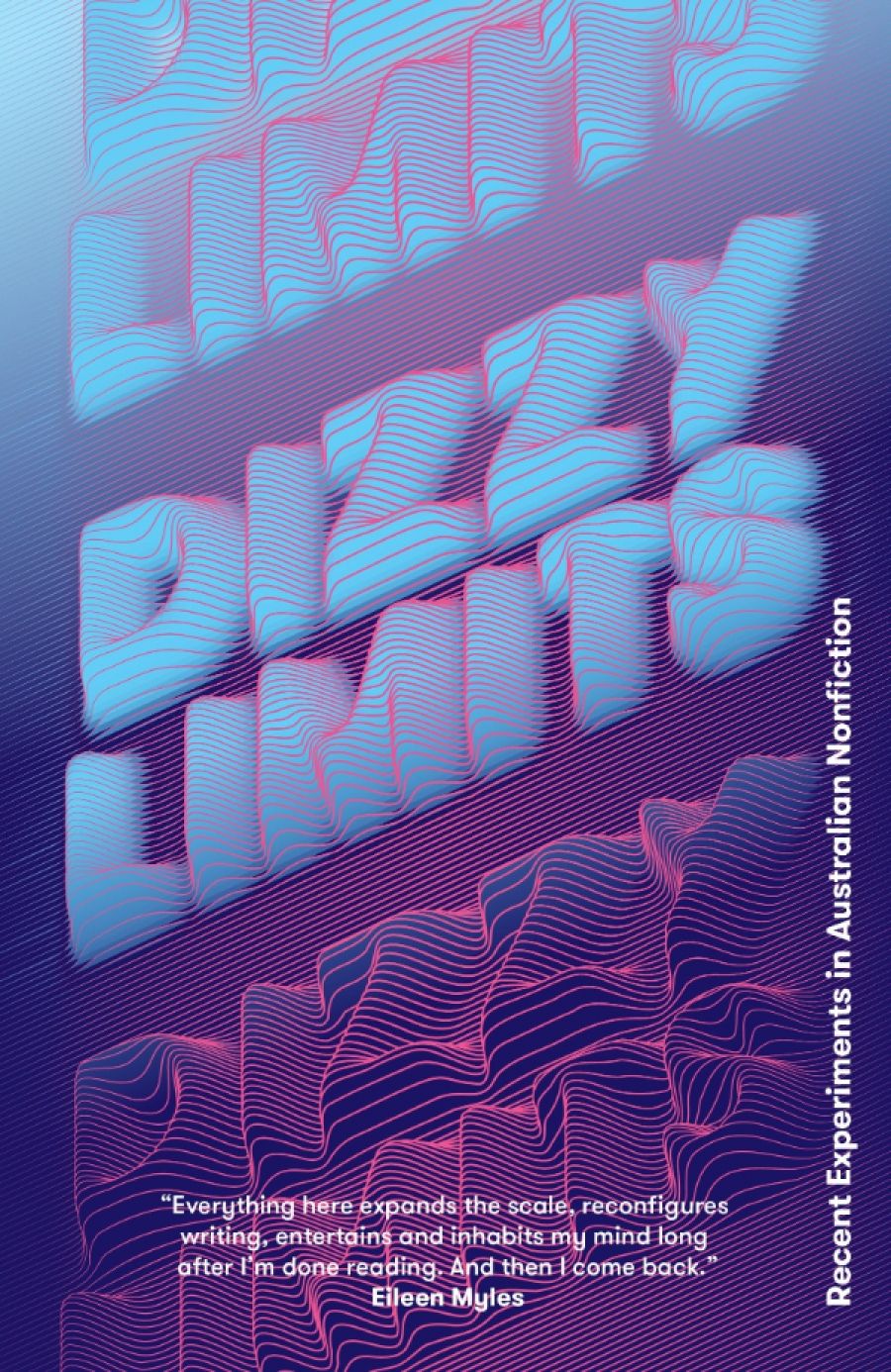

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Dizzy Limits

- Book 1 Title: Dizzy Limits

- Book 1 Subtitle: Recent experiments in Australian nonfiction

- Book 1 Biblio: $29.99 pb, 440 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Yg9WXR

For some years, the little magazine The Lifted Brow (now suspended) held a contest for ‘experimental nonfiction’ – whatever that means. Its publishing arm, Brow Books, explores this elusive concept in its latest anthology, Dizzy Limits: Recent experiments in Australian nonfiction. Perhaps the less alluring term ‘creative non-fiction’ would have been more accurate. If ‘experimental’ does indeed imply radical invention and even avant-gardism, neither is particularly evident in most of these twenty-two essays, collected from the 1990s to today, ranging in subject from leeches to lists, in style from the acutely fragmented to the merely whimsical.

The book opens with Noëlle Janaczewska’s ‘Lemon Pieces (Quelques Morceaux en Forme de Citron)’ from 1998, a supple postmodern autobiography centred on the author’s relationship with France, in particular Albert Camus, and filtered through the lemon. That is as bizarre as it sounds, but never dull, and the obsessive, diaristic tone foreshadows more recent works such as Bluets by Maggie Nelson (2009). Meanwhile, Jean Bachoura and his alter ego, Flatwhite Damascus (a self-fashioned Instagram influencer), produce ‘Tretinoin’, which does offer a certain formal innovation with its QR codes linking to YouTube videos. The piece juxtaposes Bachoura’s experiences of living in Damascus with the utter vacuity of Western consumer culture. While rough-hewn, it is instantly engaging.

Rebecca Giggs’s ‘The Leech Barometer’ sits squarely at the whimsical end of the spectrum. A piece of nature writing, it begins with a hike through the Dandenong Ranges, where she hears ‘little clicks … which could be the leeches, sticking and unsticking’. It is surely the bats, famous for their clicks, but Giggs’s surmise initiates a long meditation on the leech, showcasing her flashy, if grandiloquent, prose style:

Sometimes an earthstar, if kicked, releases a column of spores that walks on ahead – a child-ghost paddled by ferns. The smell is haemal. Wet iron. Grunge and ferment in ruts. A scrape, a skid: the ditherings of nocturnal theatre on the path. Crunched bones in scat, there, the mud rucked and feathered. Dead dust in the air. And leeches. Leeches teeming, flocking, unseen.

It is all like that, and, despite the parasitic subject matter, the sensibility is humanistic to its core, recalling Montaigne and Thoreau as it meanders through Freud, Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies, and some fascinating footnotes to history, including a passage about George Merryweather, a Victorian scientist who believed that leeches were capable of meteorological prophecy. The essay brims with promise. Giggs has all the dexterity and erudition of a significant literary talent, even if her affectations currently obscure the line of her argument and prevent the sort of incisive commentary on nature that the contemporary moment demands.

Another standout essay that experiments with a light touch is Oscar Schwartz’s ‘Humans Pretending to be Computers Pretending to be Human’, a stimulating investigation into Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) website, a crowdsourcing service recruiting human beings to perform menial tasks of which computers are incapable. As he puts it, ‘MTurk labour is conditional on the failure of developers to make new programs that could replace you.’ Schwartz’s commentaries are refreshing in their scepticism of the narrative that artificial intelligence is a deviation from human history, using the analogy of Wolfgang von Kempelen’s namesake ‘Turk’ from 1770. (That contraption, a famous chess-winning ‘machine’, in fact had a human being hidden inside.) Amazon’s scheme may sound eerie and absurd, but the essay digs up some surprising ambiguities in its examination of the ethical conundrum of the ‘automation’ of human intelligence. Among diary entries from workers, a schoolteacher unfavourably compares the monotony of her day teaching ‘slope and y-intercept equations’ with the ‘little extra money’ they make through MTurk assignments during breaktime, ‘adamant that … online crowd-sourced work is a sustainable source of labour’. Still, it is hard to be too optimistic about software consciously modelled on an exemplar of charlatanry and deception. Interesting as Schwartz’s questions are, he might have settled on a more trenchant critique of corporate exploitation.

First Nations writers are especially strong: W.J.P. Newnham’s ‘Trash-Man Loves Maree’ provides a searing, fragmentary account of the author’s homeless life in Darwin, with all the vividness and narrative playfulness of a postmodern novel; Ellen van Neerven’s ‘North and South’ is a thoughtful reflection on the writer’s life Brisbane and Sydney that aims to improve cultural literacy in a country that is ‘more likely to name our wine regions than … our language groups’. The book’s final essay, Evelyn Araluen’s ‘Cuddlepot and Snugglepie in the Ghost Gum’, constructs a powerful critique of the ways in which (among other things) the notion of the bush as a uniquely inhospitable and dangerous place in Australian literature and poetry is a colonial distortion, induced by settlers’ nostalgia.

In some ways, Dizzy Limits’ self-advertisement as ‘experimental writing’ obscures its strengths. Many of the more orthodox essays offer rigorous and searching arguments the self-consciously experimental ones lack. A few of the younger writers, in particular, seem to get sidetracked by gimmickry; they need to absorb a wider variety of perspectives in order to find their feet.

In her almost wilfully vague introduction, editor Freya Howarth shows that she doesn’t have much of an idea what experimental non-fiction is either – which, half the time, is a blessing in disguise.

Comments powered by CComment