- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Radical suffragette

- Article Subtitle: A great unsung political figure

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Sylvia Pankhurst was unquestionably the most interesting of the Pankhurst women and the only one who continues to be thought of with admiration and respect. Her life certainly deserves to be known. A talented painter, she gave up the possibility of an artist’s life for one as an activist, not only as a suffragette, but also in the labour movement and for a time as a communist, an anti-fascist, and an anti-imperialist fighting for independence for Ethiopia, where she lived for her last five years (she died in 1960 aged seventy-eight).

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sylvia Pankhurst

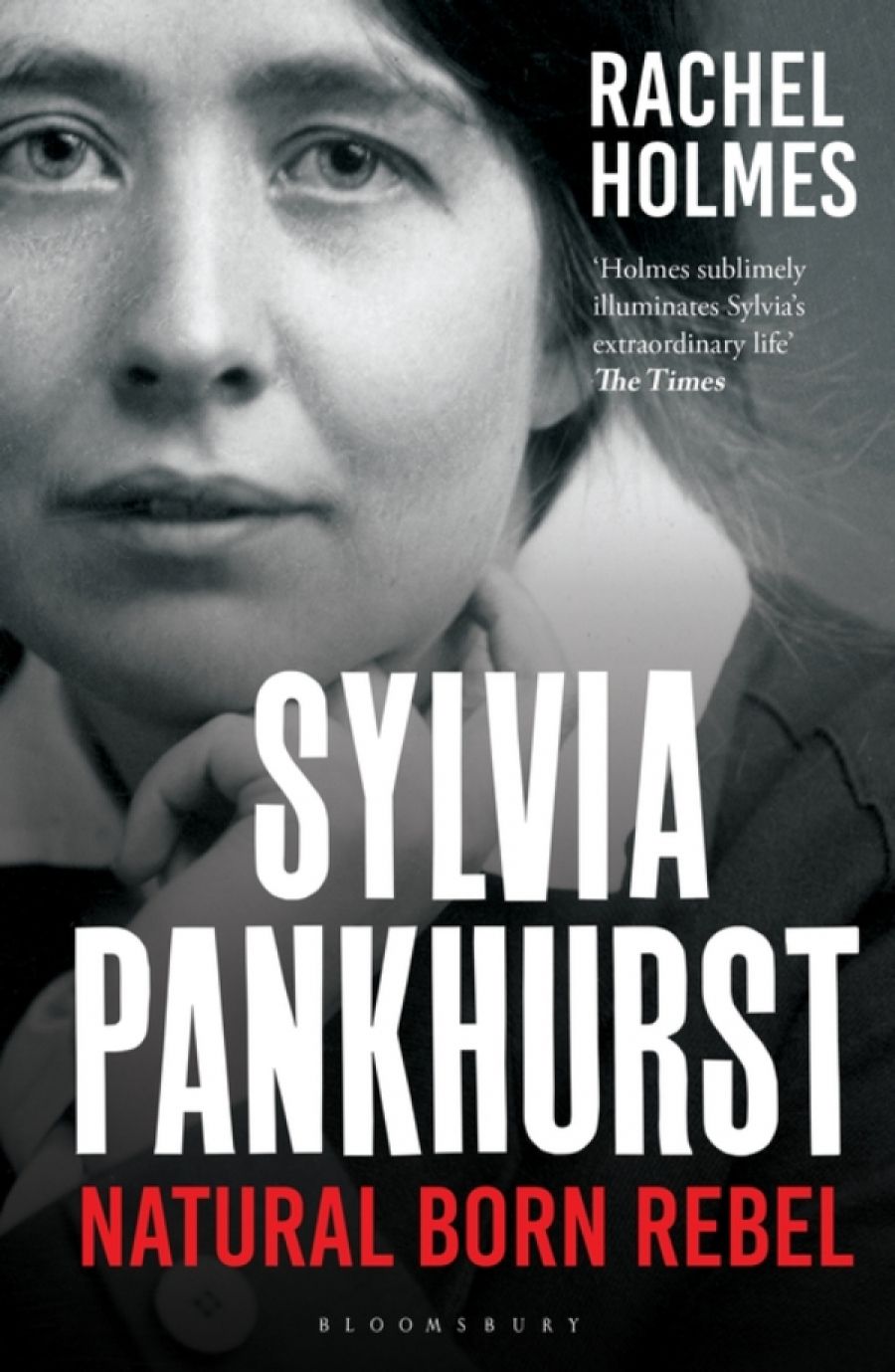

- Book 1 Title: Sylvia Pankhurst

- Book 1 Subtitle: Natural born rebel

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $45 hb, 972 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/rnQkGQ

Although Sylvia worked for a number of years in the militant women’s suffrage campaign alongside her mother, Emmeline, and older sister, Christabel, her views diverged increasingly from theirs. All the Pankhursts began as supporters of the Independent Labour party, but while Sylvia’s commitment to the labour movement and her concern about the plight of working people continued and indeed strengthened over time, that of her mother and sister evaporated and they came to feel strongly that their primary support in the suffrage struggle should come from women of means.

When her supporters were not welcomed by her family, Sylvia tried to set up her own branch of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union in East London. When Christabel refused to allow her to affiliate with their organisation, Sylvia established the East London Federation of Suffragettes, which engaged in rent strikes and set up health centres and kindergartens and workers cooperatives in addition to its continued campaign for women’s suffrage. Sylvia’s suffrage militancy was not open to question. Although she opposed the arson favoured by Christabel, she was quite prepared to break windows. She was arrested, went on hunger strike and was forcibly fed at least nine times, more often than anyone else. As Rachel Holmes shows in an excellent chapter in her biography, Sylvia endured the most appalling brutality. She had extraordinary powers of resistance, but was worn down by the torture of forced feeding, which she described as a form of rape (the descriptions provided here certainly bear that out). She never recovered fully from the ordeal.

The militant campaign came to an end with the start of World War I. But this led to a further distancing of Sylvia, an ardent pacifist, from her mother and sister, whose patriotic support for Britain and its war effort knew few bounds. While they dedicated themselves to rallies directed to recruiting men into the army, Sylvia moved around the country speaking against the war and organising anti-war rallies. She was under constant surveillance during the war, but managed to attend the Women’s International League meeting in Zurich in 1917 where the possibility of peace was discussed. A few years later, she smuggled herself out of England again in order to go to the Soviet Union, where she engaged in fierce arguments with Lenin over the best way for communism to take hold in Britain. While Lenin favoured working through the Labour Party, Pankhurst, who had come to see parliament as a form of oppression, sought other and more direct means. Their disagreements continued as Pankhurst rejected the pragmatism that led Lenin to the New Economic Policy. Her continued opposition to Lenin meant that, while Pankhurst was involved in the formation of the Communist Party of Great Britain, she was expelled from it almost immediately. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Pankhurst turned her attention to opposing imperialism and fascism and trying to stir up greater awareness about the threat that they posed.

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (standing) presiding over the Women’s War Emergency Council which she started immediately after the outbreak of WWII. The Council sought to secure improvements in the War Separation Allowances, organised deputations to Government Departments, and addressed several meetings in the House of Commons Committee Rooms (photograph by Chronicle/Alamy)

Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst (standing) presiding over the Women’s War Emergency Council which she started immediately after the outbreak of WWII. The Council sought to secure improvements in the War Separation Allowances, organised deputations to Government Departments, and addressed several meetings in the House of Commons Committee Rooms (photograph by Chronicle/Alamy)

Pankhurst’s private life was equally unconventional and interesting. For about a decade, from 1904 to just before the war, she had an intimate relationship with the Labour leader, Keir Hardie, with whom she shared many political ideals. This relationship offered her a new way of thinking about sexuality and probably strengthened her commitment to socialism. Realising that his marriage and other sexual liaisons would always limit the amount of time he was able and prepared to give her, she eventually distanced herself from Hardie. In the course of the 1920s, she fell in love with an Italian anarchist and journalist, Silvio Corio, with whom she had a child and lived happily for some thirty years, until his death in 1954.

Sylvia Pankhurst has been written about before, but never at this length or with this degree of detail or sympathy. Holmes makes no secret of her great admiration for Pankhurst, a woman she regards as ‘one of the great unsung political figures of the twentieth century’. Holmes’s admiration is so profound that nothing in Pankhurst’s life or views seems to trouble her, though others have been ambivalent about some of her views and activities. One example is the way in which Pankhurst insisted that hers was a ‘eugenic baby’, one born to the kind of intelligent parents whose offspring would benefit the world. Another is Pankhurst’s lifelong support of Haile Selassie, not only in exile but when he returned to Ethiopia in 1941. As other black leaders to whom she was close distanced themselves from the emperor because of his immense wealth and ownership of slaves, Pankhurst remained a friend and advocate, happily accepting the titles he bestowed on her on ceremonial occasions, including that of Queen of Sheba.

Seeking to make every aspect of Pankhurst’s life known to her readers, Rachel Holmes explains the context, background, and significance of every issue Pankhurst was concerned with, and of every individual with whom she interacted. This extends from her involvement with other European socialists, such as Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht, to her interest in the handicrafts that one could purchase at American railway stations. This careful detail certainly means that the book provides both a biography and a quite comprehensive history of the first half of the twentieth century in Britain and Europe more broadly. But one can’t help feeling that its length is excessive and that this book would have benefited from a ruthless editorial hand.

Comments powered by CComment